In a nutshell

The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism would have the worst impact on Turkey’s cement and electricity sectors.

Accelerating the preparatory process of instituting an emission trading system in Turkey – preferably linked to the EU’s own scheme – will help to minimise economic losses.

An active climate policy will help to ease the country’s climate-friendly transformation; revision of the target for ‘intended nationally determined contributions’ and ratification of the Paris climate agreement in parliament are two steps that can be taken immediately.

In December 2019, the European Union (EU) announced the European Green Deal to create a climate-neutral continent by 2050. The initiative focuses on three basic priorities of industrial strategy: world-leading and globally competitive industries; industries oriented towards the goal of becoming climate-neutral; and preparing for the transition to the digital future. The EU intends to achieve this transition within the framework of the circular economy.

The Green Deal is expected to transform production and trade patterns not only within the EU but also globally through the newly introduced mechanisms and regulations. The existing EU emissions trading system (ETS) will be revised to maintain economic growth in the face of possible losses in competitiveness, leading to ‘carbon leakage’ as industries relocate to countries with no carbon taxes.

The carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) is one of the measures proposed to tackle the carbon leakage problem. In essence, it is expected to serve as an import fee levied by the carbon-taxing region (in this case, the EU) on goods manufactured in non-carbon-taxing countries (in this case, Turkey).

The CBAM is expected to have a considerable effect on emissions-intensive Turkish exports (Yeldan et al, 2020) as the EU continues to be the top destination for Turkish exports (accounting for 47% of the total in 2018).

Here, we seek to shed light on the possible steps that can be taken to minimise the possible costs to be incurred by Turkish industries due to carbon pricing through an analysis conducted with input-output methodology.

In 2018, Turkey emitted a total of 520.9 Mt CO2e into the atmosphere. This sum is grouped by the greenhouse gas inventory under energy combustion (321.2 Mt), industrial and agricultural processes (130.0 Mt) and household waste (69.6 Mt). After leaving aside the household waste, we allocate the remaining 451.3 Mt of greenhouse gas emissions to the 24 sectors by making use of the TurkStat data, as reported to the UNFCCC inventory system.

In the second step, we conduct an input-output analysis to calculate the sectoral emissions embodied in the exports to the EU to analyse the potential effects of the CBAM on Turkish sectors exporting to the EU market.

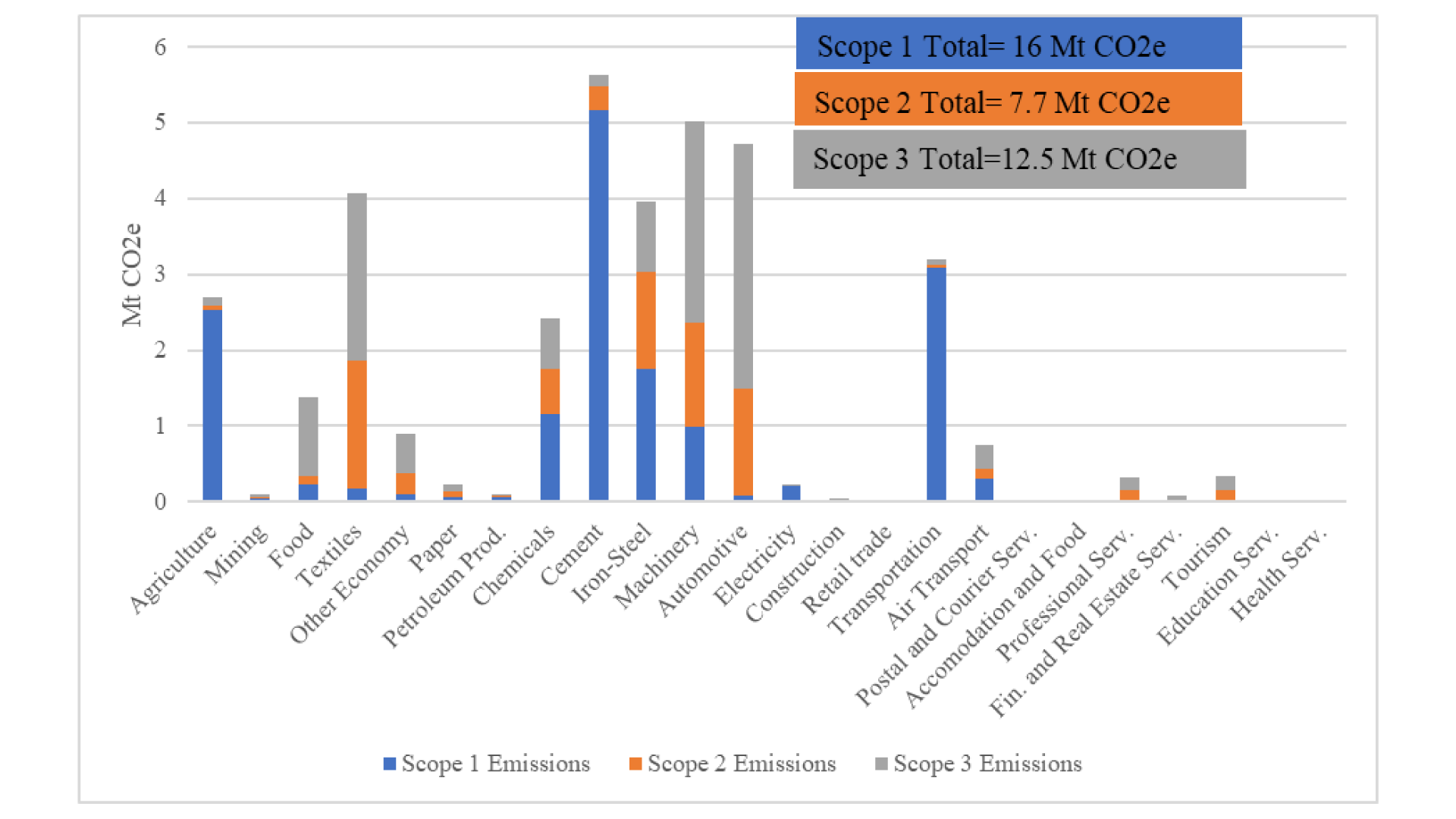

The decomposition of emissions embodied in exported goods to the EU market in 2018 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Greenhouse gas emissions embodied in Turkish exports to the EU (2018, Mt CO2e)

Turkish exports to the EU in 2018 contained 36.2 Mt of CO2e emissions (Scope 1-2-3), and the majority of them were concentrated in the cement (CE), machinery (MW), automotive (AU), iron-steel (IS) and textiles (TE) sectors.

The high carbon intensity of electricity production in Turkey is one of the vulnerabilities of the country’s exporting sectors. Figure 1 shows that the Scope 2 emissions (7.7 Mt) embedded in EU exports account for 21.3% of the total emissions (36.2 Mt CO2e).

Irrespective of their Scope 1 emissions, heavy reliance on electricity inputs in the textiles (TE), chemicals (CE), iron-steel (IS), machinery (MW) and automotive (AU) sectors would pose serious competitiveness risks in the EU export market.

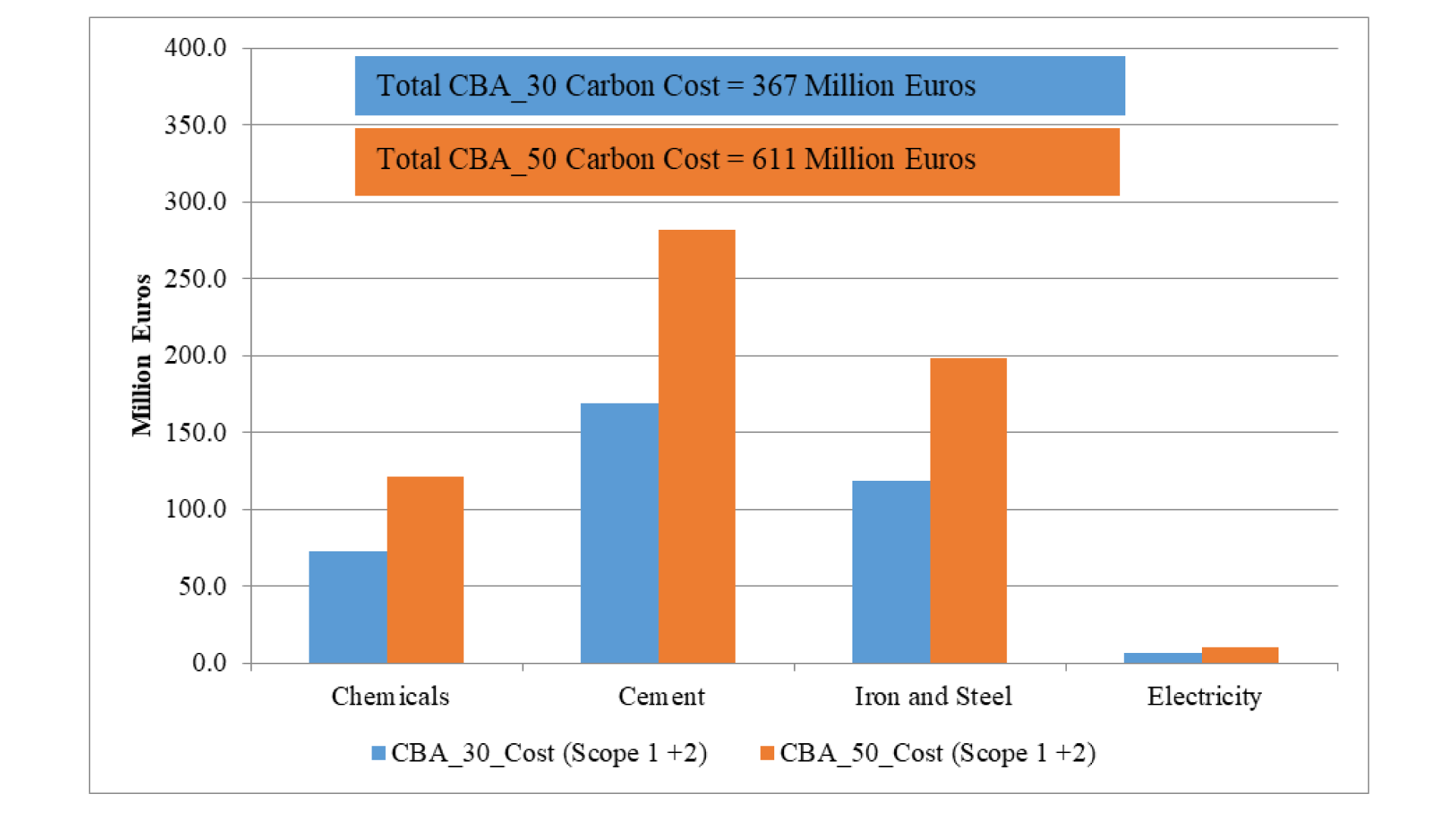

During the transitional 2023-26 period, the CBAM will apply to the Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions of handful of products grouped under the cement, iron-steel (aluminium included), chemicals and electricity sectors.

Multiplying respective Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions with carbon prices of €30 and €50 gives the carbon costs that would be faced by these sectors. Figure 2 shows that the short-run cost of the CBAM ranges between €367 million and €611 million annually.

Figure 2: Carbon costs (million euros)

While, the CBAM will affect iron-steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers and electricity at the beginning (between 2023 and 2026), its emission scope and product coverages are expected to be increased.

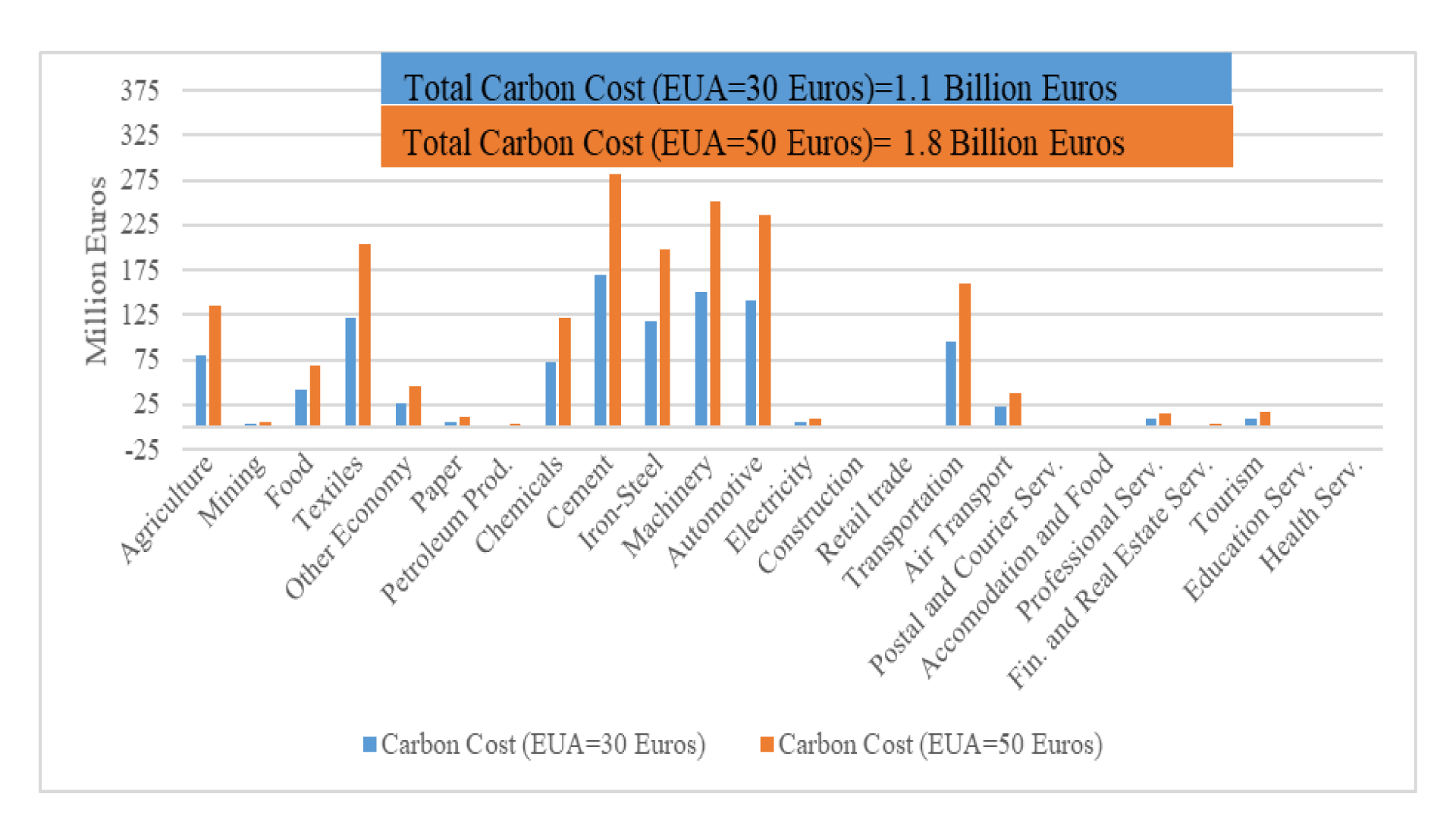

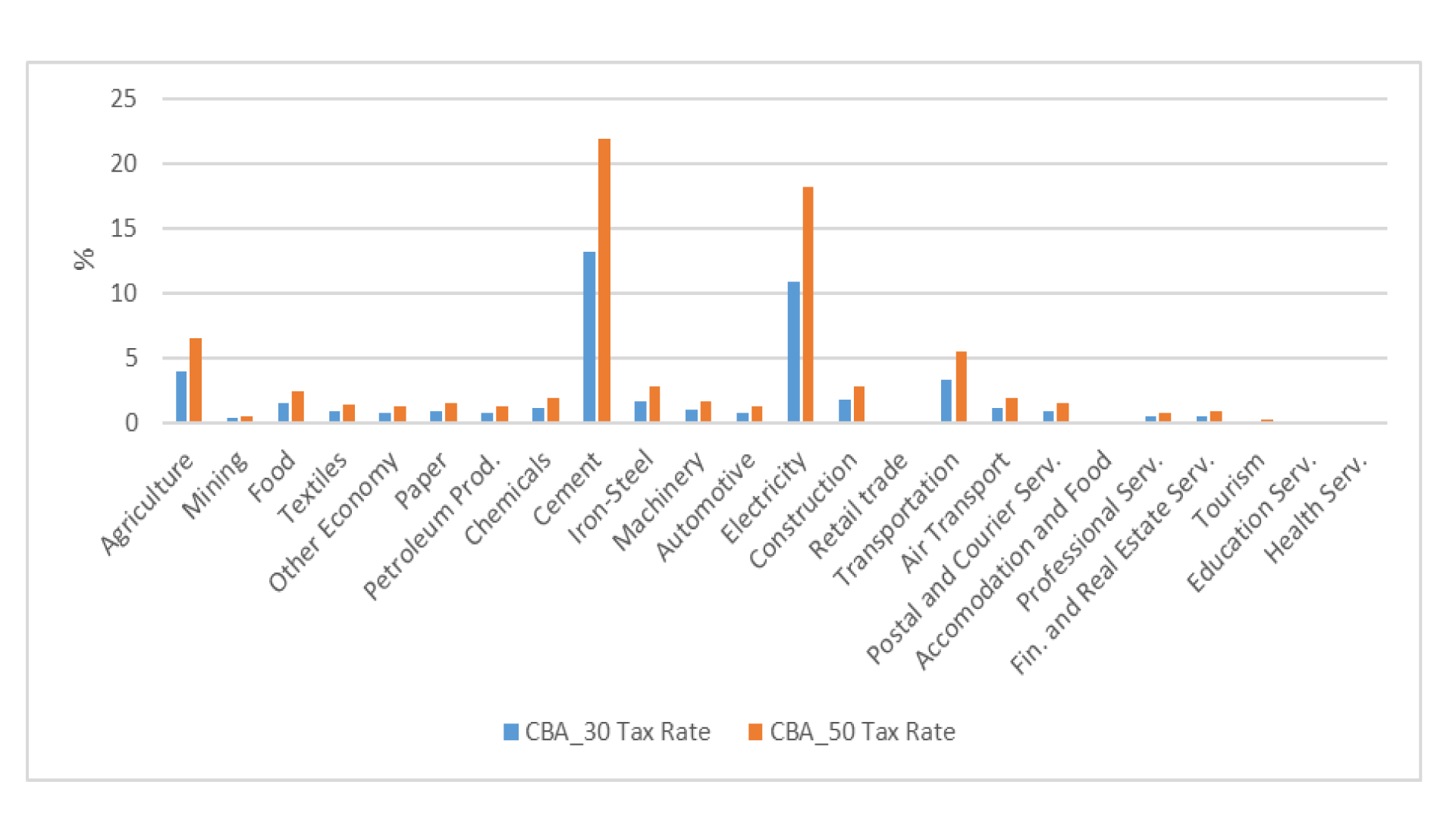

Figures 3 and 4 show the sectoral carbon costs and shadow tax rates (sectoral carbon cost as a percentage of EU export revenues) by assuming that the CBAM will cover ‘all’ emission scopes of ‘all’ model sectors in the long run.

Figure 3: Carbon costs in the long-run (all scopes)

It can be observed from Figure 4 that the CBAM would have the worst impact on the cement and electricity sectors in Turkey.

Figure 4: CBAM tax rates in the long run

Possible policy proposals

Accelerating the preparatory process of instituting an emission trading system in Turkey (preferably linked to the EU’s ETS) will help minimise economic losses. Rather than transferring to the CBAM authority, under such a system, Turkey would keep the carbon bill that ranges from €1.1 billion to €1.8 billion in Turkey that can be used to decarbonise the sectors.

Overall, a shift to an active climate policy will help Turkey to access climate finance opportunities that will ease the climate-friendly transformation of Turkish sectors. Revision of the target for ‘intended nationally determined contributions’ and ratification of the Paris climate agreement in parliament are two steps that can be taken immediately.

Further reading

Acar, S, AA Aşıcı and E Yeldan (2021) ‘Potential Effects of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on the Turkish Economy’, ERF Working Paper.

Yeldan, E, AA Aşıcı and S Acar (2020) Ekonomi Göstergeleri Merceğinden Yeni İklim Rejimi’ [New Climate Regime through the Lens of Economic Indicators], TÜSİAD Report.