In a nutshell

Forward participation in global value chains brings numerous benefits to economies, including diversification of products, enhanced productivity and increased competitiveness.

But Turkey has experienced the adverse impact of backward participation and higher backward participation indices for sectors such as chemicals and pharmaceutical products; coke and refined petroleum products; and machinery and equipment.

Emerging economies like Turkey should improve their ability to realise productivity and growth gains from global value chains, and find ways to avoid the damaging impact of backward participation on industries.

Over the past three decades, technological improvements have led to declining coordination problems and transport costs in international markets. This has altered the geographical locations of production so that nature and patterns of trade have been transformed.

The fragmentation of production processes and distribution systems across countries makes it possible to specialise in specific segments of production and use relatively cheap resources across borders. Indeed, two-thirds of international trade is now composed of intermediate goods and services (Johnson and Noguera 2012). Hence, in terms of the dynamics of contemporary world economy, benefitting from value chains in a sector is not possible without effective integration policies.

Turkish industries in global value chains

In a recent study (Yanıkkaya et al, 2020), we examine the degree of integration of Turkish sectors into global value chains. We first calculate participation indices using the methodology of OECD (2016) and then average number of production stages using the methodology of Fally (2011) and Antràs et al (2012).

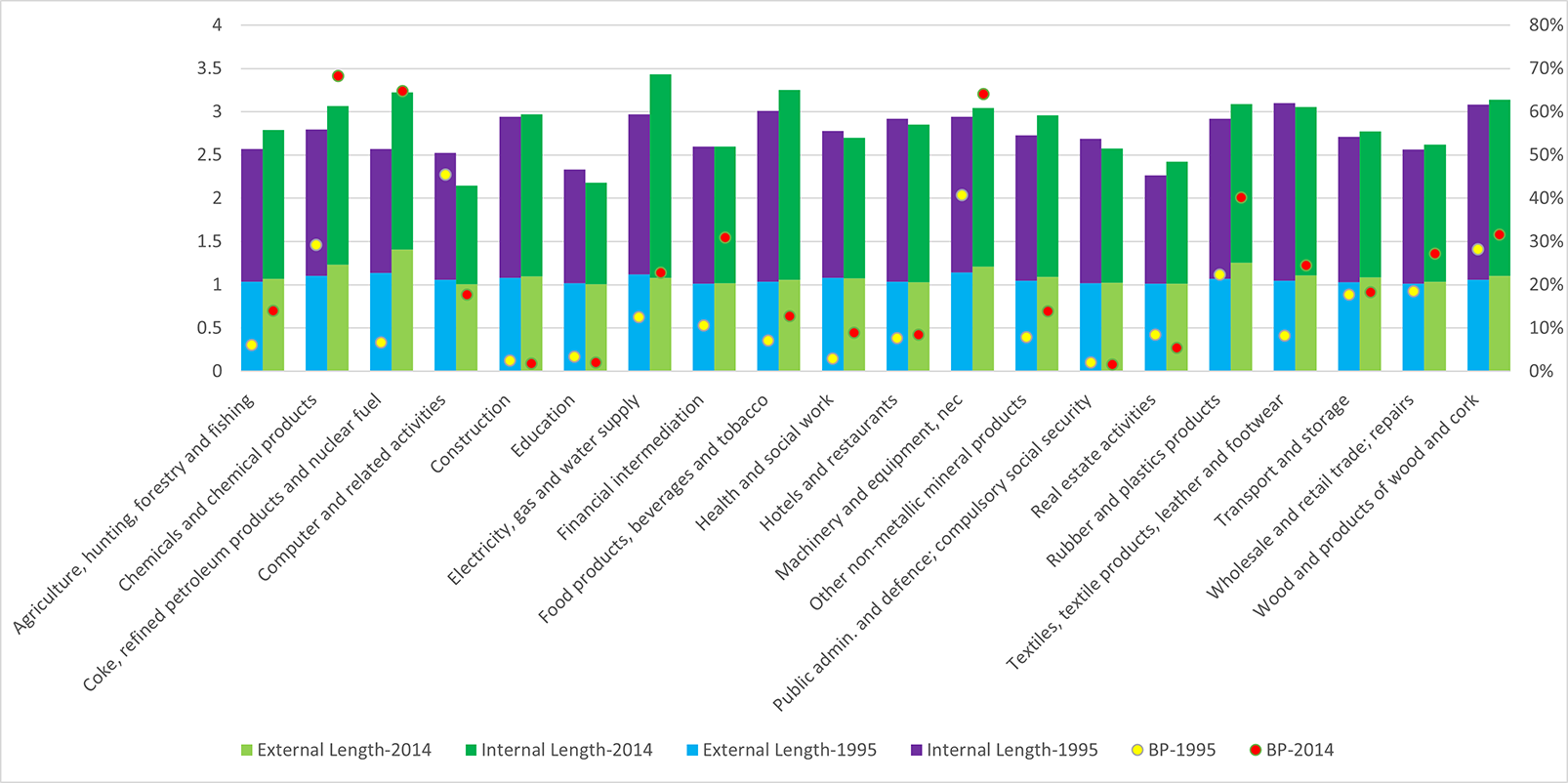

Figure 1 presents that internal lengths are higher than the external lengths for all sectors, suggesting that Turkish industries import goods or services with fewer production stages. Although there are considerable increases in backward participation in global value chains (GVCS) for some sectors such as chemicals and chemical products; coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel; and machinery and equipment, we do not observe any significant changes in GVC lengths.

While it seems that the volume of value added imports increases, the number of production stages shows no upward trend. Relative stability of external lengths thus implies no significant changes in complexity of imported intermediate products.

Figure 1: Sectoral length and backward GVC participation, 1995 and 2014

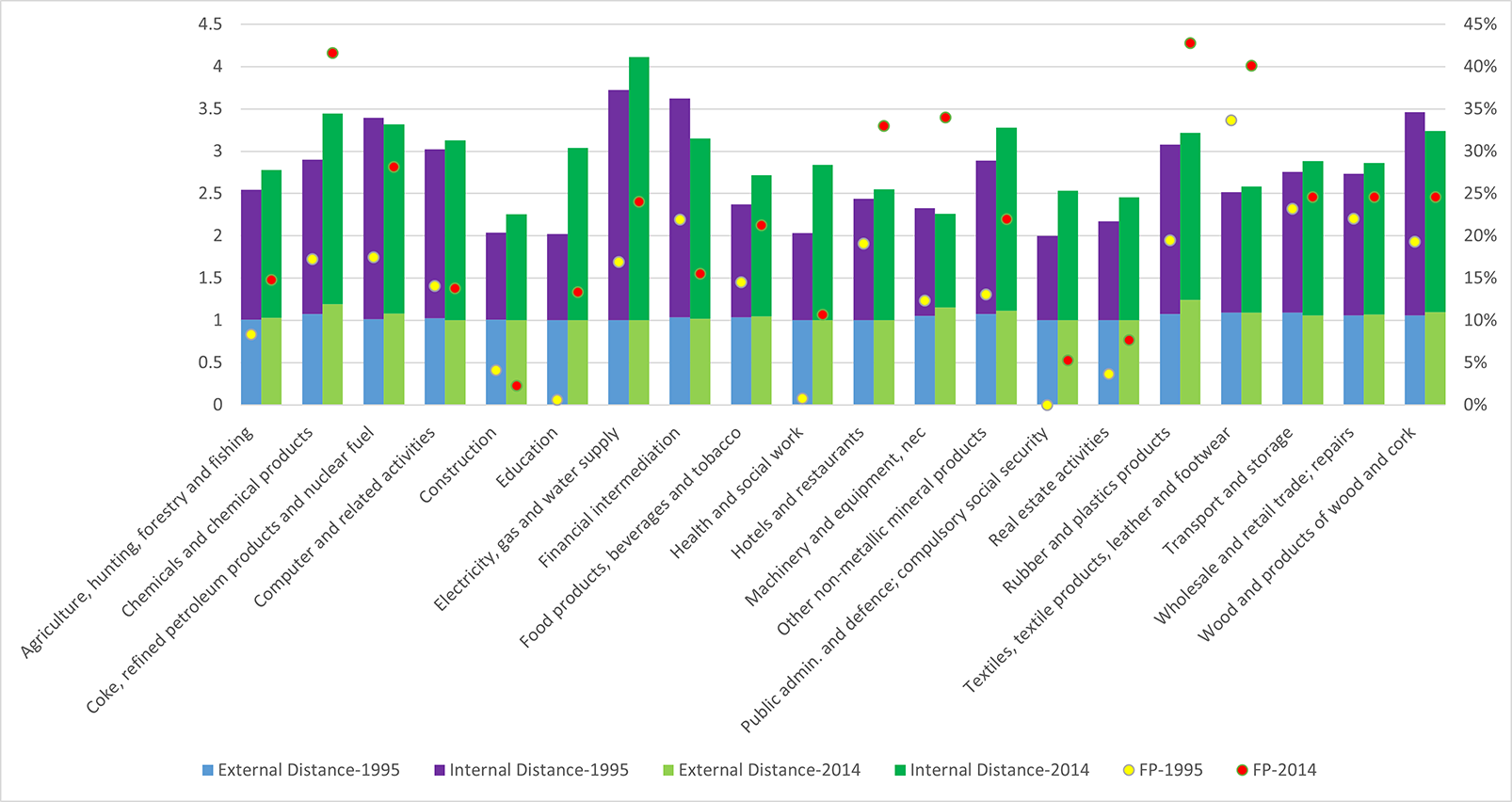

Figure 2 indicates that higher internal ‘upstreamness’ compared to external upstreamness for all sectors implies that Turkish industries export products near to final goods in international markets. Although rubber and plastics products; textiles, textile products, leather and footwear; and chemicals and chemical products sectors have relatively higher forward participation ratios, external upstreamness indices for these sectors are mostly close to one. This suggests that the goods sold by these sectors in abroad are mostly final goods rather than intermediate goods.

Overall, there are significant increases in value added in imports and exports as measured in participation rates. But these patterns do not coincide with considerable increases in complexity of products and upstreamness. In other words, the increases in length and upstreamness mainly derived from the increase in domestic length and upstreamness rather than improvements in external length and upstreamness.

Figure 2: Sectoral upstreamness and forward GVC participation, 1995 and 2014

This may also imply the preferences of multinationals in constructing local supply chains within Turkey, which leads to increases in lengths and upstreamness within country.

More importantly, it is also the sign of failure in significant upgrading of GVCs. It is evident that the impacts of GVC participations should not be assessed without considering the length and upstreamness measures since as in Turkey, indicated below, higher backward GVC participation may not lead to satisfactory gains from GVC

We then estimate our empirical models for all sectors, manufacturing industries and service industries separately for the period from 1995 to 2014.

Positive and negative effects

Our study finds that there are significantly positive impacts of exports and exports of domestic value added on total factor productivity and value added growth, providing substantial evidence for the idea of ‘learning by exporting’ for Turkish industries.

Tariffs imposed by other countries on Turkish exports have a significantly negative impact on value added growth.

The significantly and positively estimated coefficient on forward GVC participation indicates that sectors with higher participation rates have higher value added growth rates.

When we consider manufacturing and service sectors separately, we find very similar relationships between openness covariates and sectoral performance measures with some minor differences for manufacturing sectors.

But our results fail to find any significant effects of openness measures on sectoral performance of service industries. These results are quite expected because manufacturing industries produce mostly tradeable goods compared with service industries, and they are more likely to be influenced by openness measures.

For export performance, backward GVC participation seems to lower both export growth and export growth of domestic value added of manufacturing industries.

All in all, given the adverse impact of backward participation and higher backward participation indices for sectors such as chemicals and pharmaceutical products; coke and refined petroleum products; and machinery and equipment, our study shows that the steady expansion of GVCs seems to hurt these sectors through lower productivity and value added growth for Turkey.

Moreover, since forward participation in GVCs brings numerous benefits to economies such as diversification of products, enhanced productivity and increased competitiveness; countries especially emerging economies like Turkey should improve their ability to realise productivity and growth gains and find means to avoid the damaging impact of backward participation on industries.

Further reading

Antràs, P, D Chor, T Fally and R Hillberry (2012) ‘Measuring the upstreamness of production and trade flows’, American Economic Review 102(3): 412-16.

Fally, T (2011) ‘On the Fragmentation of Production in the US’, University of Colorado-Boulder.

Johnson, RC, and G Noguera (2012) ‘Fragmentation and trade in value added over four decades’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w18186.

OECD (2016) ‘Global Value Chains and Trade in Value-Added: An Initial Assessment of the Impact on Jobs and Productivity’, OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 190.

Yanıkkaya, Halit, Abdullah Altun and Pınar Tat (2020) ‘Does Openness and Global Value Chains affect the Performance of Turkish Sectors?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1447.