In a nutshell

The pandemic is likely to knock three percentage points off real world GDP relative to the level of global economic activity that would have materialised in the absence of the shock

Non-Asian emerging markets stand out for their vulnerability; Turkey, South Africa and Saudi Arabia will almost certainly see at least eight quarters of severely depressed economic activity.

Global efforts are needed to ensure swift deployments of medical resources (including vaccines when available), policy interventions that can restore the normal functioning of financial markets, as well as other measures that can support firms and households.

The Covid-19 pandemic is a global shock ‘like no other’, involving simultaneous disruptions to both supply and demand in an interconnected world economy. On the supply side, infections reduce labour supply and productivity, while lockdowns, business closures and social distancing also cause supply disruptions.

On the demand side, layoffs and the loss of income (from morbidity, quarantines and unemployment) and worsened economic prospects reduce household consumption and firms’ investment. The extreme uncertainty about the path, duration, magnitude and impact of the pandemic could pose a vicious cycle of dampening business and consumer confidence and tightening financial conditions, which could lead to job losses and investment.

Key challenges for any empirical economic analysis of Covid-19 are how to identify this unprecedented shock, how to account for its non-linear effects, how to consider its cross-country spillovers (and other observed and unobserved global factors) and how to quantify the uncertainty surrounding forecasts, given its unprecedented nature.

A rapidly growing body of research investigates the heterogeneous, non-linear and uncertain macroeconomic effects of Covid-19 across countries, sectors in individual countries, as well as on a global scale.

Pagano et al (2020) and Capelle-Blancard and Desroziers (2020) consider the effects of the pandemic on the US stock market and highlight its differential impact on various sectors of the economy. Ludvigson et al (2020) quantify the macroeconomic impact of Covid-19 in the United States using a VAR framework and a gauge of the magnitude of the Covid-19 shock in relation to past costly disasters.

Baqaee and Farhi (2020) consider possible non-linearities in response to the pandemic in a multi-sectoral model. They demonstrate how these shocks are amplified or mitigated by non-linearities and quantify their effects using disaggregated data from the United States.

McKibbin and Fernando (2020) explore the global macroeconomic effects of alternative scenarios of how Covid-19 might evolve in the year ahead, highlighting the role of spillovers. Our framework embeds the salient features of these quantitative analyses.

Covid-19 studied in a multi-country model with threshold effects

In a recent study (Chudik et al, 2020), we depart from single-country analyses and develop a multi-country econometric model that is augmented with global volatility threshold variables. These are intended to capture the effects of rare events such as Covid-19 and account for spillovers and interconnections of countries and markets.

We first document that excessive global volatility can affect output growth in many advanced economies and several emerging markets. The novelty of our work compared with the standard threshold-regression models is that non-linearity is triggered by a measure of global uncertainty rather than country-specific shocks or volatility episodes.

Next, we estimate a multi-country model (including 33 economies) augmented with these threshold effects from January 1979 through to December 2019. Our framework (which we call a threshold-augmented GVAR, or ‘TGVAR’) is an extension of the standard GVAR model surveyed in Chudik and Pesaran (2016).

Our updated model takes into account both the temporal and cross-sectional dimensions of the data, real and financial drivers of economic activity and common factors such as oil prices and global volatility. It also distinguishes between common latent factors and regional trade linkages. Country-specific models include output growth, the real exchange rate, as well as real equity prices and long-term interest rates when available.

The Covid-19 shock is identified using the International Monetary Fund (IMF) GDP growth forecast revisions between January and April 2020, under the assumption that Covid-19 was the main driver of these forecast revisions. We then quantify the economic impact of the shock by comparing the forecast of the world economy from January 2020 to December 2021 with and without the Covid-19 shock, employing ‘generalised impulse response functions’.

The impact of Covid-19 on economic activity and long-term interest rates

There are several channels through which excessive global volatility can affect economic growth. They include higher precautionary savings, lower or delayed investment (owing to increased uncertainty and weaker demand prospects) and a higher cost of raising capital, owing to higher funding costs in a volatile environment (Cesa-Bianchi et al, 2020).

Following the widespread outbreak of Covid-19, as in previous episodes of financial stress, global volatility spiked. Our country-by-country analysis establishes the importance of global volatility (whenever it exceeds an estimated threshold level) for driving subsequent output growth.

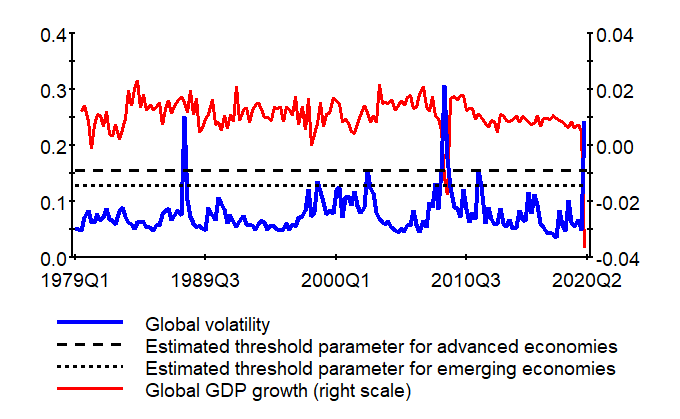

The estimated threshold level for advanced economies is 0.156 per quarter, slightly higher than the estimate of 0.129 obtained for emerging markets (Figure 1). Note that the global volatility surpassed the 0.156 level in four quarters over the period from the second quarter of 1979 to the fourth quarter of 2019 (that is, the probability of such an event occurring is very low: about 2%).

Figure 1: Global volatility and GDP growth, 1979Q1-2020Q1

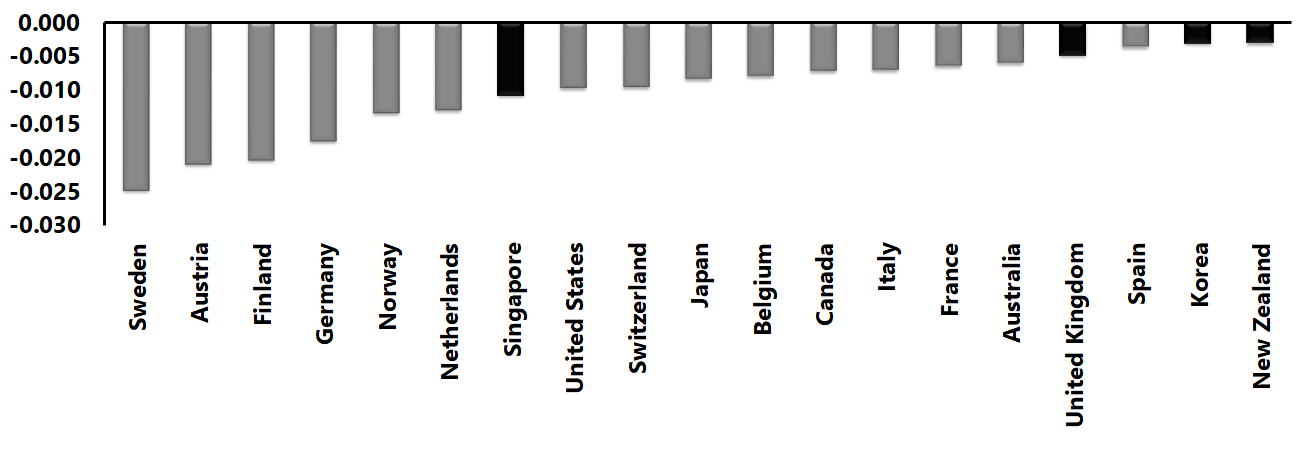

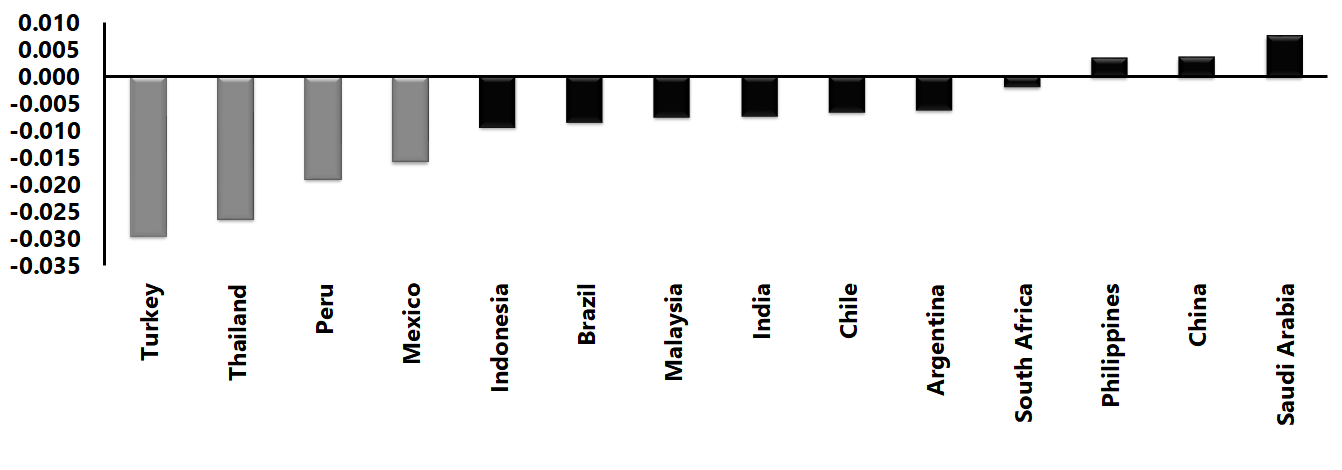

The global volatility threshold variable is statistically significant in 15 out of 19 advanced economies in our sample (80% of cases) and four out of 14 emerging economies (Figure 2). Nevertheless, threshold effects are negative in all advanced economies and all but three emerging markets. Moreover, these results become stronger when we re-run the analysis with a shorter sample from 1990.

Figure 2: Estimated country-specific threshold effects, 1979Q2-2019Q4

(a) Advanced economies

(b) Emerging economies

Note: Only the gray bars are statistically significant at the 5% level.

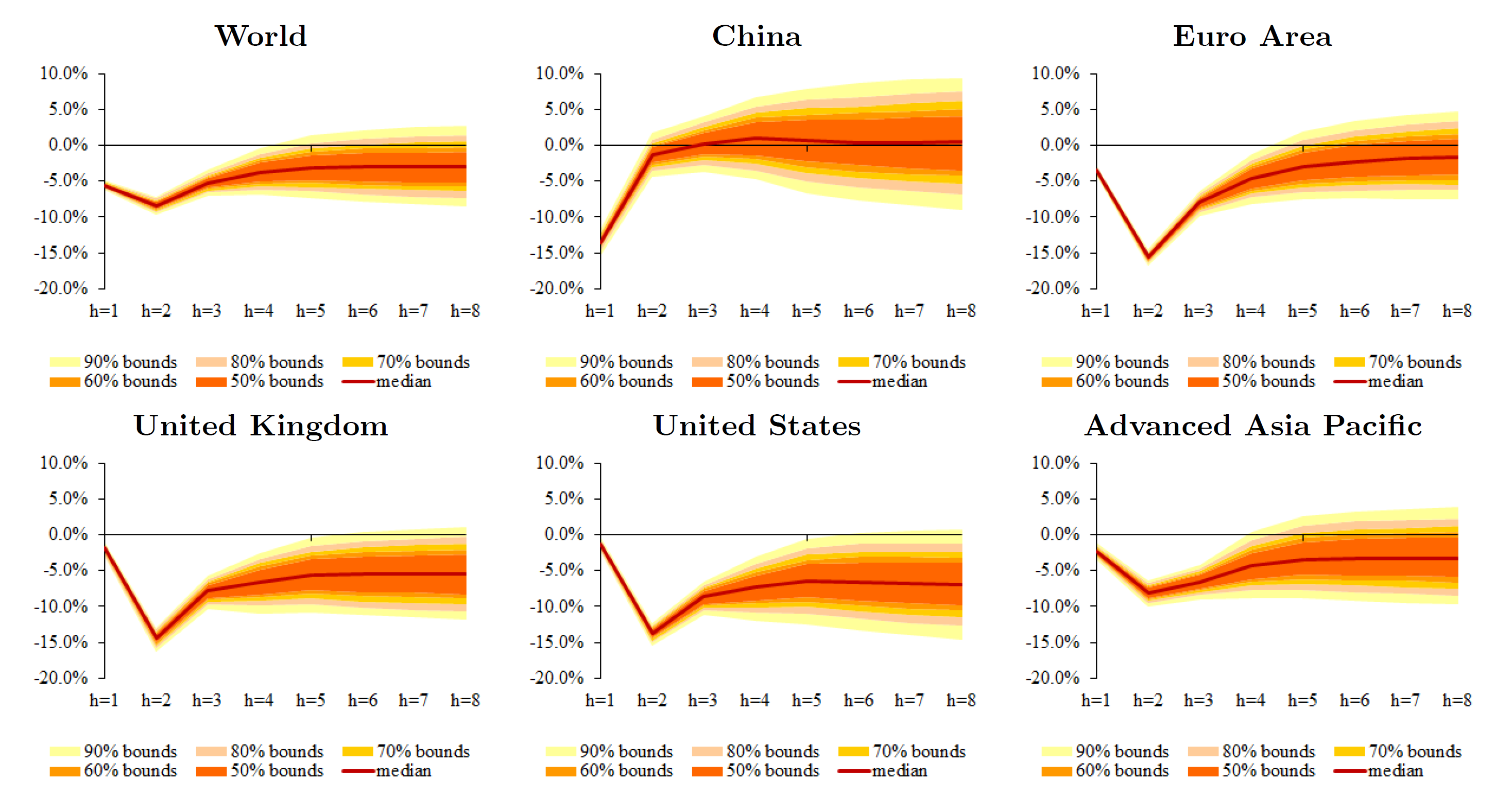

Having shown the importance of the global volatility threshold effects for subsequent output growth, we present the estimation results of our more general ‘TGVAR’ model below. Our counterfactual analysis with this model suggests that that the pandemic is likely to knock three percentage points off real world GDP relative to the level of global economic activity that would have materialised in the absence of the shock (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Counterfactual real GDP projections, 2020Q1-2021Q4

Note: The impact is in percent and the horizon is quarterly.

The United States and the UK are quite likely to experience deeper and longer-lasting effects, while China’s outcome has more than a 50% chance of being much better. The odds for the euro area are skewed negatively, but there is some probability that it recovers faster than the United States by the end of 2021.

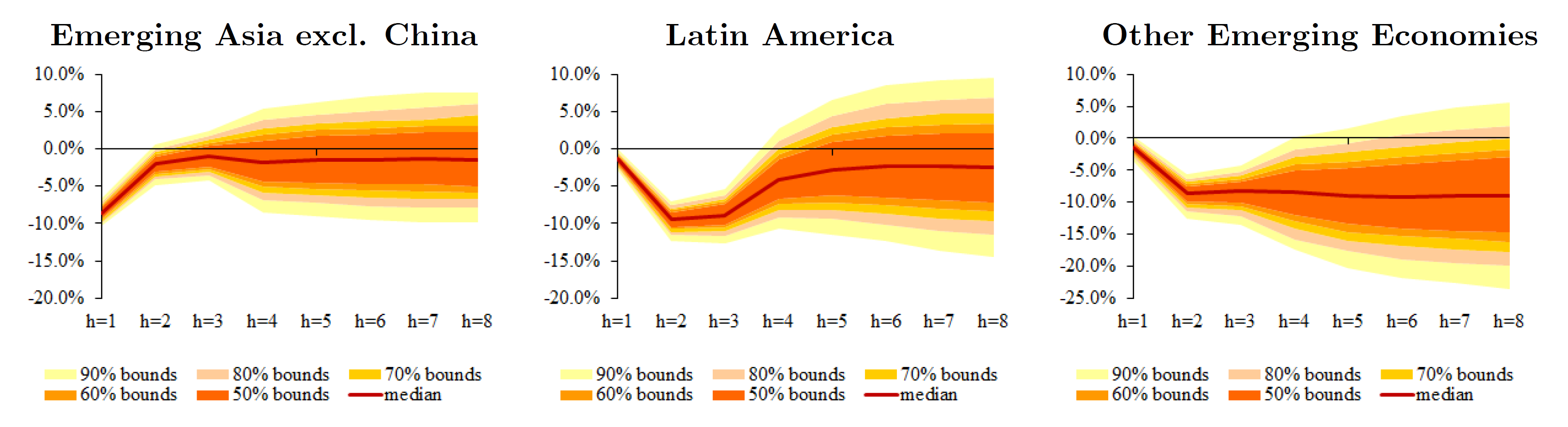

Pulled by China, the rest of ‘Emerging Asia’ has a higher chance of performing better than the global average. Non-Asian emerging markets stand out for their vulnerability (Figure 4). They will likely suffer from a significant output collapse in the first and second quarter of 2020 and have a less than 20-30% percent chance of not experiencing an output loss by the end of 2021. Turkey, South Africa and Saudi Arabia (grouped together as ‘Other Emerging Markets’) will almost certainly see at least eight quarters of severely depressed economic activity.

Figure 4: Counterfactual real GDP projections for emerging markets, 2020Q1-2021Q4

Notes: The impact is in percent and the horizon is quarterly.

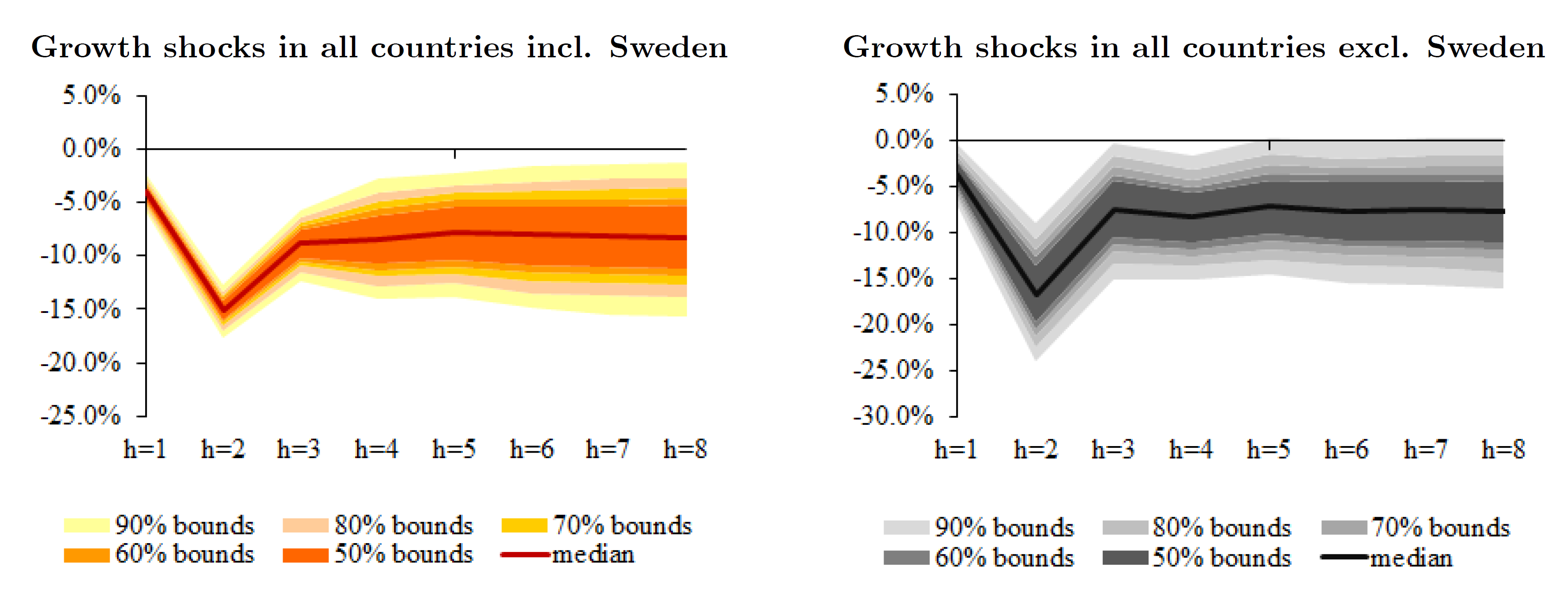

Importantly, our findings underscore the role of spillovers, which we quantify for the case of Sweden, considering its distinctly different policy approach toward the pandemic. The Swedish case illustrates that no country is immune to the economic fallout of the pandemic because of interconnections and the global nature of the shock (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Counterfactual real GDP projections for Sweden, 2020Q1-2021Q4

Notes: The impact is in percent and the horizon is quarterly.

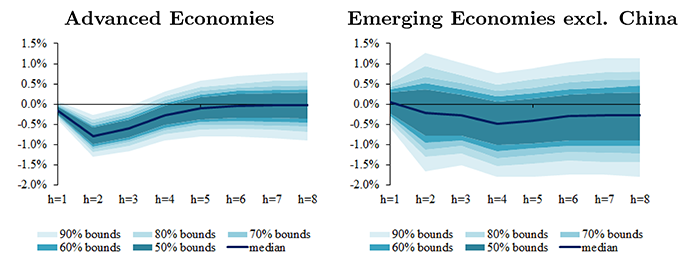

We also estimate that the pandemic is likely to lower long-term interest rates in the advanced economies by about 100 basis points below their pre-Covid-19 lows (Figure 6). This is because the crisis raises precautionary savings and dampens investment demand. But the same cannot be said with certainty about emerging market economies where borrowing rates can increase rapidly (as shown by the upper range of our counterfactual exercise).

Figure 6: Counterfactual projections for long-term interest rates, 2020Q1-2021Q4

Notes: The impact is in percentage points and the horizon is quarterly.

Concluding remarks

Our counterfactual analysis points to large and persistent negative effects of the pandemic on the world economy, with no country escaping unscathed. China and the ‘Emerging Asia’ group will fare better in the near term. The Swedish example, however, serves as a warning that no economy is immune from the negative consequences of Covid-19 in an interconnected global economy. Non-Asian emerging markets are particularly vulnerable.

These findings highlight the importance of a comprehensive and a coordinated cross-country policy response to the pandemic. This includes global efforts to ensure swift deployments of medical resources (including vaccines when available), policy interventions that can restore the normal functioning of financial markets, as well as other measures that can support firms and households.

Finally, a risk management approach to policy-making would call for activism to buy insurance against the tail events that are depicted by the distribution of likely outcomes. These efforts would be likely to limit the amount of scarring.

Further reading

Baqaee, DR, and E Farhi (2020) ‘Nonlinear Production Networks with an Application to the Covid-19 Crisis’, CEPR Discussion Paper 14742.

Capelle-Blancard, G, and A Desroziers (2020) ‘The stock market and the economy: Insights from the COVID-19 crisis‘, VoxEU.org, 19 June.

Cesa-Bianchi, A, MH Pesaran and A Rebucci (2020) ‘Uncertainty and Economic Activity: A Multi-country Perspective’, Review of Financial Studies 33(8): 3393-3445.

Chudik, A, K Mohaddes, MH Pesaran, M Raissi and A Rebucci (2020) ‘A Counterfactual Economic Analysis of Covid-19 Using a Threshold Augmented Multi-Country Model’, NBER Working Paper 27855.

Chudik, A, and MH Pesaran (2016) ‘Theory and Practice of GVAR Modeling’, Journal of Economic Surveys 30(1): 165-97.

Ludvigson, SC, S Ma and S Ng (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the Macroeconomic Effects of Costly Disasters’, NBER Working Paper No. 26987.

McKibbin, WJ, and R Fernando (2020) ‘The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios’, CAMA Working Paper 19/2020.

Pagano, M, C Wagner and J Zechner (2020) ‘COVID-19, asset prices, and the Great Reallocation‘, VoxEU.org, 11 June.

This column was first published at Vox.