In a nutshell

Current debt threats in EMDEs arise mainly from debt architecture and the dominance of volatile debt forms, primarily bonds denominated in foreign currencies.

EMDEs need to strike a balance between temporary accommodative measures and the post-shock monetary-fiscal policy mix that will prevent a deflationary spiral, without worsening indebtedness and financial fragility.

Global initiatives for supporting the debt sustainability of EMDEs are advancing, but measures are needed to reform international debt architecture, capital flows management and exchange rate misalignments.

According to the seminal work of Irving Fisher (1933), Hyman Minsky (1986) and Ben Bernanke (1995; 2018), the triggers for global shocks occur periodically. But several factors affect whether they lead to traumatic crises and depressions, or just repetitive cycles of growth slowdown that may reverse quickly. Countries that are over-indebted and more financially fragile are more vulnerable to external shocks. Financial distress transmits to the real sector through a mechanism of debt distress, which ends up in recessionary waves.

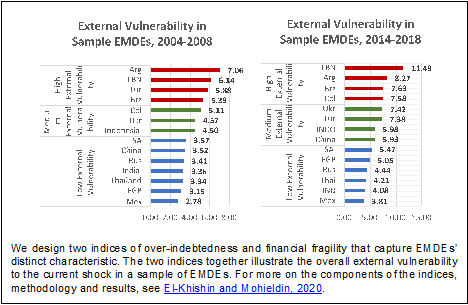

Notwithstanding the distinct features of the current crisis, in recent work (El-Khishin and Mohieldin, 2020), we show that emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) are even more vulnerable now than they were at the onset of the global financial crisis. This suggests that the impact of the current shock might be more devastating and recovery more distant (Figure 1). Several factors are contributing to the increased vulnerability, as we explain below.

Figure 1: External vulnerability index in sample EMDEs

Non-government debt largely drives debt distress in EMDEs

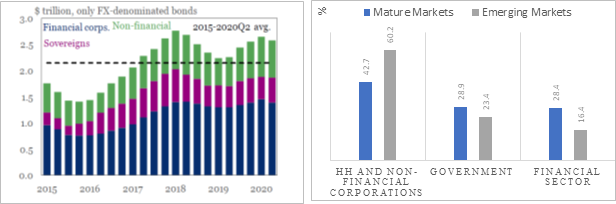

The combined debt of households and non-financial corporations constitute more than 60% of total debt, according to Institute of International Finance data (Figure 2). Corporate bonds constitute the largest share of foreign currency bond issuance in emerging markets (EM-30), as the figure shows.

Despite their appealing yields, relatively high ratings and other benefits compared with more mature markets, corporate bonds pose high risks in a crisis. Such volatile forms of debt are accompanied by high default risks and they are not eligible for restructuring.

Middle- and low-income countries, where financial and non-financial bond markets are still immature, may suffer more from the dominance of sovereign bonds as a source of finance. Sovereign bonds pose the same, if not higher, risks of high volatility and ineligibility for restructuring (Stiglitz and Rashid, 2020).

Figure 2: Overall debt composition in emerging markets

Source: IIF, in Tiftik and Mahmood (2020).

Reactions to the global financial crisis aggravated many pre-existing conditions

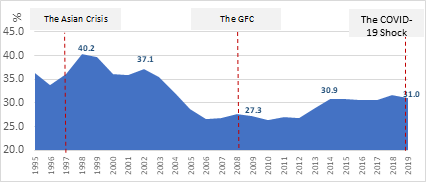

While EMDEs have acted to stabilise their external debt burdens since the global financial crisis (Figure 3), many are adopting debt architecture and maturity compositions that lead to increased external vulnerability and weak resilience to sudden shocks.

In excessive fear of entering a debt-deflation spiral, EMDEs expanded their growth trajectories through a pattern of cheap private lending, loose accommodative policy measures and, in some cases, unmonitored fiscal expansion. Such measures, usually advised to be temporary, have further expanded over-indebtedness and financial fragility in EMDEs.

Figure 3: External debt as a percentage of GDP in EMDEs (1995-2019)

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019

The disconnect between real and financial markets is becoming more evident over time since the outbreak began

The Covid-19 crisis initially resulted in a liquidity shock that largely stemmed from capital outflows from EMDEs, exchange rate shocks as well as rising credit spreads with the onset of the crisis. Nonetheless, financial markets overcame early losses, reflecting either investors’ denial of the severity of the crisis or a response to stimulus packages and debt restructuring plans.

Increased low cost finance, large monetary expansion and injected liquidity led to a surge in corporate bonds and speculative activities, disturbing the connection between financial markets and real sector performance during the crisis. The increased speculative activities and concerns about growing Ponzi finance activities together suggest that ‘Minsky’s moment’ may be approaching.

Following Minsky, ‘big government’ or a ‘big bank’ can help to avert economic disasters, as well as promoting global monetary harmony

Hyman Minsky attributed financial tranquillity and mild cycles during the period 1944-1970 to sound policies that were adopted early enough, curing the early onset of economic cycles. Bernanke picked up Minsky’s big government hypothesis, as did Paul Krugman (2020). Their advocacy of big government was found in the US Federal Reserve’s activities as a lender-of-last resort during the global financial crisis.

Likewise, Krugman’s ‘permanent stimulus’ proposal in the current Covid-19 shock may work for the US economy – given the low interest rate environment and the US dollar characteristics. But applying such recipes to EMDEs needs more caution. EMDEs, which are already characterised by fiscal imbalances, prolonged recessions, weak multipliers and, in many cases, politically driven discretionary interventions, must handle them more cautiously.

Fiscal stimuli might be inevitable after a crisis; yet, macro-fiscal structural imbalances in many EMDEs might make countercyclical interventions ineffective, even hazardous, and lead to more vulnerabilities.

Global and country-level actions are thus becoming more urgent, not just to improve EMDEs resilience during the Covid-19 shock, but also to achieve better debt sustainability outcomes after the crisis. In this regard, we offer the following proposals.

Growth models in EMDEs need to be remastered in the long term towards more reliance on sustainable domestic sources of finance

EMDEs with relatively young populations and potential demographic dividends need to adopt inclusive growth policies and develop their domestic financial markets to channel dividends, leverage domestic savings and fill financing gaps. Sustainable domestic sources of finance are key to decreasing reliance on short-term external finance, widening fiscal space, overcoming debt maturity mismatches and hence decreasing external vulnerability.

Post-shock accommodative measures should be balanced with longer-term policies that ensure the prudence of financial systems in the face of growing credit demand

EMDEs have already started early corrective actions to counter the effect of the shock. Nevertheless, the continuation of current monetary and financial easing in light of the perceived growth slump is highly alarming. EMDEs need to adopt more conservative policies and credit growth patterns need to be revised, even if this means some sacrifice in growth rates over the medium term.

Another lesson from the global financial crisis is that fears of deflation should not lead to the preservation of systems of cheap unmonitored finance or fiscal expansion. In line with Bernanke (2018), we argue that maintaining financial system resilience with prudent policies is necessary to prevent panics, even if this will have undesirable impacts on credit growth. This is particularly important in light of the perceived too-optimistic sentiment driven by monetary expansion and injected liquidity.

While overall debt build-up is always alarming, current debt threats arise mainly from debt architecture

Hence, debt portfolio management in EMDEs is essential in light of perceived risks arising from highly volatile, short-term and foreign currency-denominated bonds. We also recommend that EMDEs maintain flexibility in their exchange rates during the shock. More flexible exchange rates reduce financial fragility during shocks and can discourage short-term speculative activities in bonds markets, particularly in imprudent and underdeveloped financial systems.

At the global level, Minsky’s argument that global monetary and financial management have a role in preventing debt crises cannot be more relevant

While the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) provides some breathing space for IDA countries (the world’s poorest) during the shock, will not address the fundamental debt problems in non-IDA countries. Rather, such countries need innovative measures and more private sector participation in debt relief, debt buybacks and debt swaps (Ellmers, 2020; United Nations, 2020b).

Recent global efforts and actions are advancing in this regard. As part of the ‘Initiative on Financing for Development in the Era of Covid-19 and Beyond’, member states of the United Nations and international institutions are discussing actions to address debt issues through introducing global harmonised actions, as well as accounting for the heterogeneity of debt conditions across different countries (United Nations, 2020a).

We highlight the importance of renovating the global financial architecture to consider currency exchange realignments, proper management of capital flows and more actions related to debt moratorium and restructuring, especially in light of the current low interest rate environment, which might facilitate debt reform processes in EMDEs.