In a nutshell

Egypt’s demographic profile promises an ever-rising supply of young labour force, productivity and tax revenues for the next three decades – but sooner or later, automation is bound to retrench millions of jobs.

Meeting the rising expectations of future workers should begin with a transformation of the education system and encourage future generations to consider non-academic and vocational career paths.

Stronger efforts are required to foster K-12 education and boost skill acquisition for young generations, and to invest in continuous education and skill upgrading.

The phenomenon of labour market polarisation has been well documented in industrialised economies since the 1980s, but there has been less research on emerging and developing countries, especially those in the Middle East and North Africa. Polarisation, defined over occupational categories, clusters employment in high-education, high-wage occupations and low-education, low-wage occupations while occupations in the middle stagnate.

There are three leading explanations for labour market polarisation:

- Automation, driven by the rise of artificial intelligence algorithms, less costly and enhanced computer power, is typically viewed as a replacement for routine occupations.

- Sectoral employment shifts – away from manufacturing and towards services – reduce wages and lower demand for employment in high productivity growth occupations compared with other occupations.

- Consumption patterns arising from increased demand from high-wage workers for goods and services provided by low-skilled workers (Goos et al, 2014); Autor and Dorn, 2013; Michaels et al, 2013; Hilgenstock, 2018; and Siegel et al, 2018).

In this column, I present evidence of occupational polarisation in Egypt, its impact on wage differentials and interdependence with the education system. Drawing on Labour Market Panel Survey (LMPS) data (1998-2018) and labour force surveys (1997-2018), three issues emerge from employment polarisation in Egypt:

- Marked wage compression in absolute and relative terms along the occupational spectrum.

- Deskilling of college-educated workers once they enter the labour market.

- A needless escalation in demand for higher education.

Employment polarisation

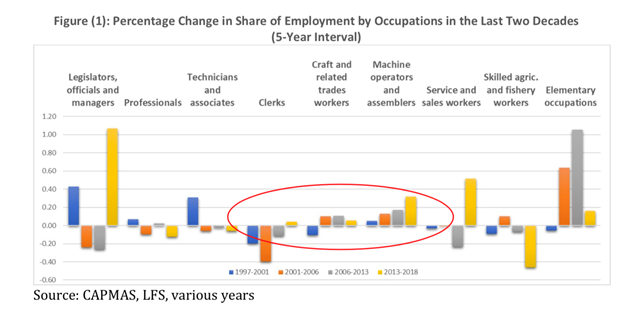

Figure 1 shows shifts in employment shares along nine broad occupational categories, tracking changes over the last 20 years in five-year intervals. The three occupations on the right (services, skilled agriculture, and elementary occupations) are typically held by low-wage, least educated workers; the three in the middle (clerks, craft and trade workers, and plant operators) normally held by vocational and non-tertiary educated workers; while the three on the left (managers, professionals and technicians) are claimed by high-education, high-wage workers.

Figure 1 suggests employment polarisation towards either the far right or far left of the occupational range. By comparison, there are minor changes in mid-range occupations (circled region).

To narrow down the comparability across nine occupational categories, I use the ‘occupation-task-education distribution’ approach, a cruder allocation of occupations based on the most dominating task within each occupation (as in Acemoglu and Autor, 2011). It is worth noting that this approach carries its own weaknesses. For example, it assumes homogeneity of tasks within occupations, and does not consider workers’ adaptability to new tasks. Using a continuum of occupations is probably best to address these drawbacks (El-Hamidi, 2020).

The occupation-task-education distribution distinguishes between three broad groups:

- Cognitive, skilled, non-routine-task occupations, which involve abstract problem-solving tasks and are filled by college graduates. They managerial, professional and technical occupations.

- Routine-task occupations, which consist of codifiable tasks that follow clear instructions and are regarded as a substitute for the following occupations: clerical, sales and machine operator occupations.

- Manual, unskilled, non-routine-task occupations, which require some flexibility, physical skills and human interaction, but not problem-solving skills. They are the least prestigious and the core labour market for the least educated. Such tasks usually characterise occupations such as service, transport, labourers and farming occupations.

Using LMPS data, Figure 2 displays the three task groups and verifies employment polarisation in Egypt towards manual and cognitive. Declining employment in routine occupations, typically catering for high school and non-tertiary graduates, averaged 32% in the last two decades. This is a faster pace of polarisation than what is observed in developing and developed countries alike since 1995: 8% and 12% respectively (World Bank, 2016).

On the other hand, it is evident that employment gains in Egypt were biased in favour of manual occupations. The 20-year period logged a 67% rise in manual occupations. Cognitive occupations added only 14% of jobs, overwhelmingly clustered in managerial positions in real estate and mining sectors.

Figure 2 also presents changes in the ratio of college to non-college workers by task groups. It shows that college-educated workers were increasingly working in jobs for which they were overqualified. Between 1998 and 2018, routine occupations were taken three times more by over-fitted workers, while manual jobs employed over one and half times tertiary educated workers.

Wage compression

Wage polarisation in Egypt was not as evident as employment polarisation. In advanced economies, and as a result of deficient supply of college graduates, wages in cognitive occupations grew both in absolute and relative terms, intensifying inequality (Autor et al, 2002, 2003; Levy and Murnane, 2004; Autor et al, 2006, 2008; Acemoglu and Autor, 2011; Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018).

The rise in college graduates in Egypt, especially in the last decade, has had adverse effects on the value of a college degree in the labour market. Adjusted for inflation, Figure 3 shows college-educated workers had gained the least in purchasing power between 1998 and 2018. By comparison, workers with non-tertiary degrees, including basic education, gained at least 13% in real wages.

In fact, rising real wages of non-college-educated workers contributed to narrowing their wages with those of college-educated workers. For example, the wage gap between college and basic educated workers closed by more than 10%, and contracted by 14% between workers with college education and workers with high school diploma.

The labour market versus the education system

Compared to labour markets, the education sector, especially higher education, is highly regulated, generously subsidised and adversely managed. Despite sincere efforts to privatise higher education in the last decade, still 80% of college-educated workers are graduates of public universities.

Figures 2 and 3 deliver two main messages:

- A negligible rise in cognitive occupations, disappearing routine occupations and a surge in manual jobs (Figure 2). It is not surprising to see the most educated competing against the less educated, who in turn are pushing the least educated out of the labour market.

- College-educated workers suffer deteriorating wages relative to non-college-educated workers. In additions, wages in manuals jobs are rising faster than wages in other occupations (Figure 3). Changes in relative and absolute wages, a predictor for private rates of return to education, send cues to prospective workers and guide future demand on higher education.

Accordingly, it is expected to see declining demand for college education, or at least plateauing.

But the education sector has yet to respond to market forces and the demand for higher education has yet to realise the true market valuation of college degrees. For example, in a span of ten years (2005-16) college graduates increased in absolute numbers by 25%. While one may cite the impact of refugees, vocational school graduates dropped by 38%, and high technical institutes (non-tertiary) graduates rose by only 10%. (CAPMAS, Annual Bulletins for Pre-University and Higher Education various).

In other words, current employment polarisation, along with conforming wages in the labour market are conveying the following message to new generations: ‘you need a college degree to get a manual job’. This is a message that perpetuates an insatiable demand for tertiary education and a labour market that is aggressively depleting investment in human capital.

Policy recommendations

Employment polarisation revitalises the economy when employment rises in high-wage occupations. In the case of Egypt, there is evidence of employment polarisation towards the lower end of the occupational ladder. While this is not a problem as long as the market is responding to consumption and production cues, it is critical when the workforce feeding these production lines is increasingly overqualified.

In 2014, Egypt’s newest constitution stretched the years of state-funded compulsory education till the end of secondary or its equivalent. This necessitates conscious efforts to increase public expenditure on K-12 education. Yet the allocated budget among tertiary and non-tertiary education is disproportional.

First, enrolment in higher education represents 12% of total enrolment in K-12. But as recently as 2019, the national budget for education allocated 32% of its budget to tertiary education, contributing further to deskilling the labour force, while alternative non-academic and vocational paths that offer better employment opportunities are financially deprived and culturally discouraged.

Egypt’s demographic profile promises an ever-rising supply of young labour force, productivity and tax revenues for the next three decades. Sooner or later, automation is bound to retrench millions of jobs.

Meeting the rising expectations of future workers should begin with a transformation of the education system and encourage future generations to consider non-academic and vocational career paths. Stronger efforts are required to foster K-12 education and boost skill acquisition for young generations, invest in continuous education and skill upgrading.

Further reading

Acemoglu, Daron, and David H Autor (2011) ‘Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings’, in Handbook of Labor Economics Vol. 4B edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, 1043-1171, North-Holland.

Adermon, A, and M Gustavsson (2015) ‘Job polarization and task-biased technological change: Evidence from Sweden, 1975–2005’, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 117(3): 878-917.

Autor, David H, and David Dorn (2013) ‘The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market’, American Economic Review (103(5): 1553-97.

Autor, David H, Lawrence F Katz and Melissa S Kearney (2008) ‘Trends in US wage inequality: Revising the revisionists’, Review of Economics and Statistics 90(2): 300-23.

Autor, David H, Frank Levy and Richard J Murnane (2003) ‘The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (4): 1279-1333.

Autor, David H, Lawrence F Katz and Melissa S Kearney (2006) ‘The Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market’, American Economic Review 96(2): 189-94.

Bárány, ZL, and C Siegel (2018) ‘Job polarization and structural change’, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 10(1): 57-89.

Das, MM, and B Hilgenstock (2018) The exposure to routinization: Labor market implications for developed and developing economies, International Monetary Fund.

Goos, M, and A Manning (2007) ‘Lousy and lovely jobs: The rising polarization of work in Britain’, Review of Economics and Statistics 89(1): 118-33.

Goos, M, A Manning and A Salomons (2014). ‘Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring’, American Economic Review 104(8): 2509-26.

Green, DA, and BM Sand (2015) ‘Has the Canadian labour market polarized?’, Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique (48(2), 612-46.

Levy, Frank, and Richard J Murnane (2004) ‘Education and the changing job market’, Educational Leadership 62(2): 80.

Michaels, Guy, Ashwini Natraj and John Van Reenen (2014) ‘Has ICT Polarized Skill Demand? Evidence from Eleven Countries over Twenty-Five Years’, Review of Economics and Statistics 96(1): 60–77.

Spitz-Oener, A (2006) ‘Technical change, job tasks, and rising educational demands: Looking outside the wage structure’, Journal of Labor Economics 24(2): 235-70.

World Bank (2016) World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends.