In a nutshell

Plans for reconstruction in Syria should critically examine the dynamics of the country’s social and economic policies in the years before 2011, when the economy was characterised by crony capitalism and severe income inequality.

It is essential that policy-makers take all the necessary measures that can undermine sectarian influences and consolidate national identity.

Having a transparent power-sharing plan that is based on the rule of law is of fundamental importance for restoring peace and prosperity by establishing an inclusive social contract.

The Syrian civil war has been by far one of the most violent wars of the twenty-first century. This has to do with the magnitude of battlefields, displacement waves, proxy wars and the multidimensional grievances that have developed during a decade of war.

The need come up with a comprehensive plan to address all these problems has become inevitable (Makdisi and Soto, 2019). The empirical results of our research suggest a number of recommendations and policy implications (Abosedra et al, 2020).

Power-sharing

Having a power-sharing plan that achieves inclusive economic growth and development is essential. This was lacking in the pre-2011 era, which contributed to the civil war. Hence, a power-sharing plan is of fundamental importance for restoring peace and prosperity by establishing an inclusive social contract.

International assistance

The participation of international organisations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is vital for the success of the reconstruction process. That process needs to put as a priority an economic agenda that can put the Syrian economy back on track.

Respect public demands

The weak responsiveness of politicians to public demands can trigger anger and discontent. When these demands happen to be among specific demographic groups, they antagonise these groups against the state. Thus, policy-makers should address these demands in a serious way.

Corruption

The consequences of various forms of corruption can augment hatred between different segments of the population, including those associated with the ruling party and those who have been systematically marginalised.

Rule of law

The absence of the rule of law exacerbates grievances. Having a robust rule of law can promote social cohesion and protect the society from any surge in violence levels.

Syria’s economic performance

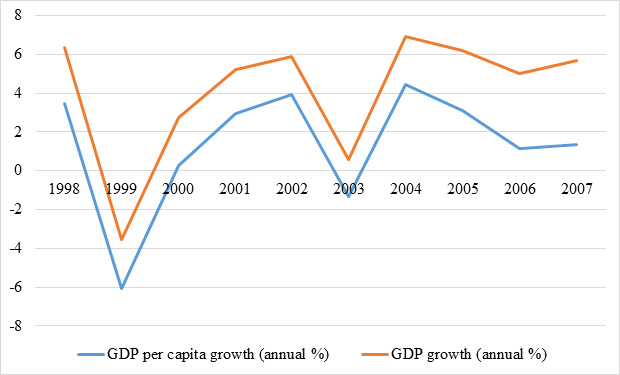

Syria witnessed a substantial improvement in economic performance from 2000, when President Bashar Al-Assad took office (see Figure 1). The new economic era had been characterised particularly by the substantial removal of tariffs that year and the introduction of massive privatisation measures. These liberalising measures led to relatively significant improvements in living standards and national GDP per capita.

But the fruits of this prosperity were shared unevenly among economic classes, widening income and wealth inequality. This, in turn, has exacerbated grievances within the Syrian society, especially regional ones between rural and urban areas (Burner, 2015). Several studies have linked extreme inequality levels in Syria to the control of the national economy by very few well-connected businessmen, especially those in Damascus and Aleppo (Goulden, 2011).

Figure 1: GDP per capita and GDP growth in Syria, 1990-2007

Source: World Bank Development Indicators (WDI).

Reconstruction plans

Plans for reconstruction should therefore examine critically the dynamics of Syria’s social and economic policies in the years before 2011, which noticeably enhanced the power of a small ethnic group that is well-connected, resulting in crony capitalism and intensifying inequality levels.

In addition to establishing a power-sharing mechanism among the different ethnic groups and the ethno-political configurations of power, policy-makers and politicians should respect the demands of their citizens by paying more attention to their daily suffering. Besides enhancing power-sharing and taking note of what people are demanding, it is essential that policy-makers should take all the necessary measures that can undermine the sectarian influence and consolidate the national identity.

Another important measure is enforcement of the rule of law. Fearon (2011) studies the effect of four out of six of the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) governance indicators on the onset of a civil war. These measures are: ‘investment profile,’ ‘corruption,’ ‘rule of law’, and ‘bureaucratic quality’. Fearon (2011) suggests that all four measures are effective in reducing the probability of war, with the rule of law and corruption being the sturdiest among the four indicators.

In fact, corruption was a key driver behind the Arab uprisings in the MENA region. (Makdisi and Soto, 2019). More specifically, the improvement in the investment profile indicator – defined by the ICRG to be a measure of the political stability of a country – lessens the possibility of the occurrence of a civil war (Fearon, 2011).

Accordingly, policy-makers are encouraged to ensure the existence of long-term political stability, which in turn stimulates investment as a result of an increase in investors’ confidence in the country. This is particularly relevant for Syria to attract foreign investments that will aid in the restoration process of the country’s infrastructure.

Further reading

Abosedra, Salah, Ali Fakih and Nathir Haimoun (2020) ‘Ethnic Divisions and the Onset of Civil Wars in Syria’, ERF Working Paper No. 1384.

Burner, D (2015) Syria’s Economy: Picking Up the Pieces, Chatham House.

Fakhoury, T (2019) ‘Power-sharing after the Arab Spring? Insights from Lebanon’s Political Transition’, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25(1): 9-26.

Fearon, JD (2011) ‘Governance and civil war onset: Background Paper’, World Development Report, World Bank.

Goulden, R (2011) ‘Housing, inequality, and economic change in Syria’, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38(2): 187-202.

Makdisi, S, and R Soto (2019) ‘Economic agenda for post-conflict reconstruction’, unpublished manuscript.