In a nutshell

The costs of the crisis are a moving target: global, policy and social responses are fluid.

As time goes by, the main driver of expected costs is the health system with transparency at a premium.

National policy responses should follow a ‘sequencing without delay’ approach with transparency at a premium.

Research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows that economists generally have difficulties forecasting severe economic downturns (IMF, 2018). Similarly, World Bank research finds that rare and large negative shocks – so-called ‘black swan’ events – are even harder to predict than run-of-the-mill recessions. Thus, predicting the costs of the current dual shock is difficult (World Bank, 2018).

Nevertheless, close inspection of the changes in the World Bank’s growth forecasts (Figure 1) can shed light on the beliefs of the institution’s economists about the nature of the impact of the dual shock on growth expectations for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in 2020-21.

Figure 1: Fluid estimates of the costs of the crisis – changes in World Bank growth forecasts

Panel A shows the changes in the growth forecasts between those conducted in 1 April 2020 and those published in October 2019, for MENA as a whole, the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), developing oil exporters and developing oil importers. The sharpest drop in 2020 growth forecasts corresponds to the developing oil exporters, followed by the developing oil importers and then by the GCC countries.

Panel B illustrates how forecasts can be fluid and subject to change when new data become available. Between 19 March and 1 April 2020, World Bank economists sharply increased their estimates of the cost of the dual shock, and downgraded growth rates in 2020 and 2021 for MENA.

To the extent that the full repercussions of the dual shock have not been fully captured in economic forecasts, it is safe to conclude that our estimates of the costs of the crisis are conservative; they can be interpreted as lower bound estimates of the costs.

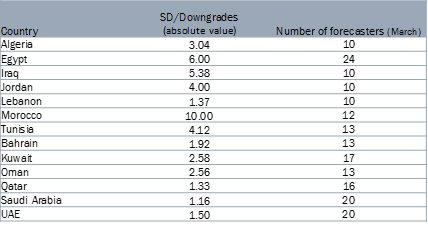

Uncertainty also dominated private sector forecasts for the MENA region between December and March (see Table 1). The variance across forecasts as of March is orders of magnitude larger than the magnitude of the growth downgrades (relative to December). Furthermore, the magnitude of the growth downgrades is correlated with the variance of the forecasts.

Table 1: Private sector forecasts for MENA 2000 GDP growth

Source: Focus Economics.

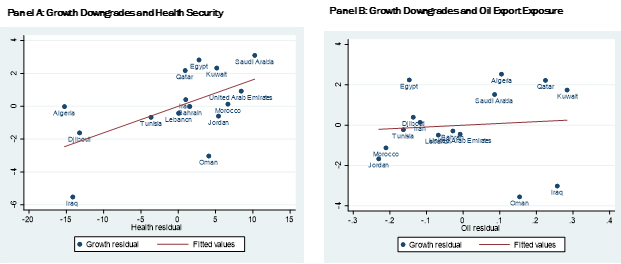

A closer look at the World Bank forecast adjustments suggests that the changes in the forecasts are systematically related to initial pre-existing conditions, particularly each economy’s health system (see Figure 2). But oil export exposure had a significant effect only in the March forecast, with little influence in the April adjustment.

Figure 2: Correlates of the costs of the crisis: growth downgrades, oil export exposure and health security

March forecast:

April forecast:

To net out the effects of pre-existing conditions and cyclicality, we decompose the change in economic expectations as follows: C = V + P + O – CYC. Where C is the change between ex post and ex ante expectations; V is change due to the spread of the virus; P is change due to the collapse of oil prices; O is other pre-existing conditions; and CYC is change due to cyclical factors.

While Figure 2 illustrates effects from the first two elements – namely Covid-19 and oil price-related changes – Lebanon provides a good example of the role of pre-existing conditions. Downgrades in not only the forecasted growth rate in 2020 but also in growth rates estimated for 2019 suggests that prior to Lebanon’s exposure to Covid-19 and the oil price collapse, the country was already facing crises, such as the larger than expected and still increasing fiscal deficit.

To deal with the dual shock, a two-pronged approach can be pursued. One is immediate and related to the health emergency. The other concerns forward-looking policy reforms. Authorities could sequence and tailor their responses to the severity of the shock. That is, it might be desirable to focus first on responding to the health emergency and the associated economic contraction.

Fiscal consolidation and structural reforms associated with the persistent drop in oil prices and pre-existing challenges are also very important, but with proper external support, they can wait until the health emergency subsides. After the crisis, budget-neutral reforms such as debt transparency and reforms of state-owned enterprises will also come to the fore.

In summary, the costs of the crisis are a moving target: global, policy and social responses are fluid. As time goes by, the main driver of expected costs is the health system with transparency at a premium. National responses should follow a ‘sequencing without delay’ approach.

Further reading

An, Zidon, Jaoa Tovar Jalles and Prakash Loungani (2018) ‘How Well Do Economists Forecast Recessions?’, IMF Working Paper.

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Vegh, Carlos, Guillermo Vuletin, Daniel Riera-Crichton, Juan Pablo Medina, Diego Friedheim, Luis Morano and Lucila Venturi (2018) ‘From Known Unknowns to Black Swans: How to Manage Risk in Latin America and the Caribbean, World Bank.

Register to attend our upcoming live webinar on On the Economics of the Dual Shock in MENA on May 12, 2020 at 4:00 pm Cairo Local Time.