In a nutshell

Almost a quarter of households in Egypt experienced food insecurity and 16% were exposed to at least one type of economic shock during the year 2017/18.

Poor households were four times as likely to have experienced food insecurity and more than twice as likely to have experienced shocks compared with rich households.

Households mostly used ‘consumption rationing’ – reduced spending on health, food or education – and social capital to cope with economic shocks or food insecurity.

Rural and urban households face different risks that could lead to adverse economic shocks. Poverty and vulnerability to shocks are interlinked given the limited opportunities of poor households to use assets or diversify income (Dercon, 2002). The 2018 wave of the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) allows us to explore the nature of economic shocks and food insecurity experienced by Egyptian households as well as the preventive measures and coping mechanisms that they adopt. We find that there is still a need for more effective social programmes with wider coverage to mitigate household vulnerability to shocks and food insecurity.

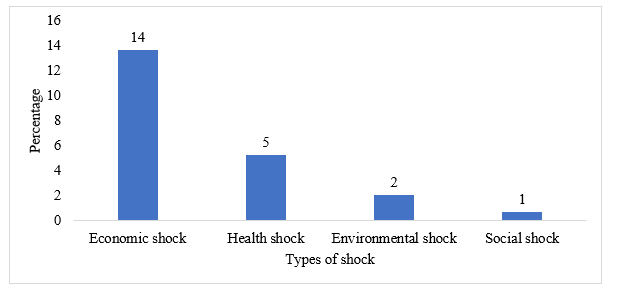

Around 16% of Egyptian households were exposed to at least one type of shock during the year preceding the ELMPS interview. As Figure 1 shows, economic shocks were the most frequently reported type of shocks. Reduced income (12%) followed by loss of employment (7%) were the most prevalent types of economic shocks. In addition, around 25% of the households experienced food insecurity during the month preceding the survey. About 15% of households experienced food insecurity alone, while about 10% experienced both food insecurity and at least one type of shock simultaneously (Helmy and Roushdy, 2019).

Figure 1: Percentage of households exposed to shocks during the past year by type of shock

Source: Helmy and Roushdy (2019). Note: Multiple shocks are possible

Households in the poorest quintile by wealth (23%) were more than twice as likely to experience a shock as those in the fourth (12%) and fifth (9%) wealth quintile groups. Similarly, the likelihood of exposure to food insecurity was higher among the poorest households. About 39% of the poorest quintile households experienced food insecurity compared with only 11% of the richest quintile households.

Disability and food insecurity were linked. This relationship is as expected since both food insecurity and disability are higher among the poor. In addition, exposure to shocks was associated with low subjective wellbeing (Sieverding and Hassan, 2019).

Exposure to shocks was higher in rural areas than in urban areas. More households were exposed to shocks in rural Upper Egypt (21%) and rural Lower Egypt (20%), followed by the Alexandria and Suez Canal region (19%), Urban Upper Egypt (15%), Urban Lower Egypt (14%) and Greater Cairo (3%).

There was a similar regional disparity for food insecurity, which was higher in the 1,000 poorest villages (31%), followed by other rural areas (28%) and 21% among urban households. The two regions that had the highest rates of food insecurity were rural Upper Egypt (32%) and Alexandria and Suez Canal (31%) (Helmy and Roushdy, 2019).

In terms of social protection coverage, around 57% of Egyptian households received either non-contributory benefits (such as Sadat/Mubarak pensions, Takaful and/or Karama, and other types of social assistance) or contributory benefits (such as retirement pensions) compared with 62% in 2012 and 68% in 2006. This decline could be due to the decrease in the percentage of households with at least one actively contributing member as well as the drop in social insurance coverage (Selwaness and Ehab, 2019).

The decrease in health insurance and social security coverage (Selwaness and Ehab, 2019) is alarming given that informality of employment is associated with exposure to shocks among households. Households with heads working in the informal private sector were twice as likely to be exposed to a shock (20%), compared with households with heads working in the formal private or public sectors (10-11%). In addition, around 23% of the households with heads working outside an establishment were exposed to a shock compared with only 12% among those of heads working inside an establishment (Helmy and Roushdy, 2019).

On the other hand, the percentage of households covered by any type of social assistance transferred by the government increased from 9% in 2006 to 13% in 2018 (Selwaness and Ehab, 2019). Despite receiving social assistance, beneficiary households still reported higher exposure to risks compared with non-beneficiary households. For example, 31% of households that received Takaful or Karama were exposed to shocks compared with 15% among non-recipient households. The results were similar for other social assistance and food ration cards.

Food insecurity was common among households receiving social assistance and food ration cards. Over a quarter of the households that received food ration cards suffered from food insecurity during the month preceding the ELMPS survey.

Furthermore, the degree of food insecurity was highest among households receiving Takaful and Karama conditional cash transfers or other types of social assistance. Less than 9% of the households receiving retirement pensions reported severe food insecurity compared with 18% of the households receiving social assistance and 15% of the Takaful and Karama beneficiaries (Helmy and Roushdy, 2019).

In contrast to social assistance, households with health insurance were less likely to experience a shock in 2017/18: 15% versus 18% among those without health insurance. The case was similar for those with social insurance: 11% experienced a shock versus 19% among those without social insurance.

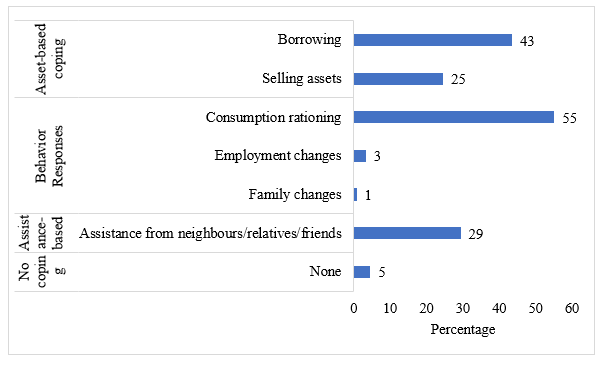

Looking at strategies adopted by households to cope with shocks, Figure 2 shows that ‘consumption rationing’ (55%) followed by borrowing (43%) were the two most frequently reported coping mechanisms. Social capital was an important safety net, as almost a third (29%) of Egyptian households reported seeking assistance from relatives and friends in response to a shock (Helmy and Roushdy, 2019).

Figure 2: Percentage of households using different coping mechanisms, households with shocks during the past year

Source: Helmy and Roushdy (2019). Notes: Multiple strategies are possible

About 28% of households borrowed money from their relatives or friends, while 5% borrowed from a bank or a moneylender. Consumption rationing as a coping strategy primarily consisted of reduced spending on health (36%), eating less food (35%) and lower spending on education (22%).

Borrowing and purchasing on credit were more prevalent as coping strategies among households headed by men, while assistance from neighbours, relatives and friends were more frequently reported by households headed by women. Similarly, around 34% of the households that experienced food insecurity borrowed or purchased food on credit, while 19% received assistance from neighbours, relatives and friends to cope with food insecurity.

Our findings point out to the importance of providing poor households with formal shock-responsive social safety nets. Safety nets need to be flexible and sufficient to strengthen households’ capacity to respond to shocks without using stressful coping strategies that harm their human capital.

Increasing social and health insurance coverage is crucial given that our results show access to formal, inside establishment jobs and to social security benefits were associated with considerably lower exposure to shocks and food insecurity in Egypt.

Further reading

Dercon, S (2002) ‘Income Risk, Coping Strategies, and Safety Nets’, World Bank Research Observer 17(2): 141-66.

Helmy, I, and R Roushdy (2019) ‘Household Vulnerability and Resilience to Shocks in Egypt, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Selwaness, I, and M Ehab (2019) ‘Social Protection and Vulnerability in Egypt: A Gendered Analysis’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Sieverding, M, and R Hassan (2019) ‘Associations between Economic Vulnerability and Health and Wellbeing in Egypt, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).