In a nutshell

Nearly one fifth of the Arab population are extremely poor by global standards, and two thirds are either poor or vulnerable to multidimensional poverty.

Better and more regular monitoring of Arab poverty is required – for example, through the establishment of a poverty observatory similar to those in China and Latin America.

No matter how good they are, social policies will be insufficient to remedy the problem of Arab poverty.

The World Bank has recently updated its numbers on poverty from 2013 to 2015. The following provides a quick overview of what the latest datasets have to say about poverty in Arab states. There are four stylised facts to take away from the numbers before we discuss what they mean for the medium to long-term outlook.

Four stylised facts

First, according to the common measure of extreme poverty – the $1.9 per day international poverty line – the Arab region’s poverty headcount ratio in 2015 was 6.7%. This may seem low, but it is the third highest among developing regions (after sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia). To put things in perspective, the global average was 10%.

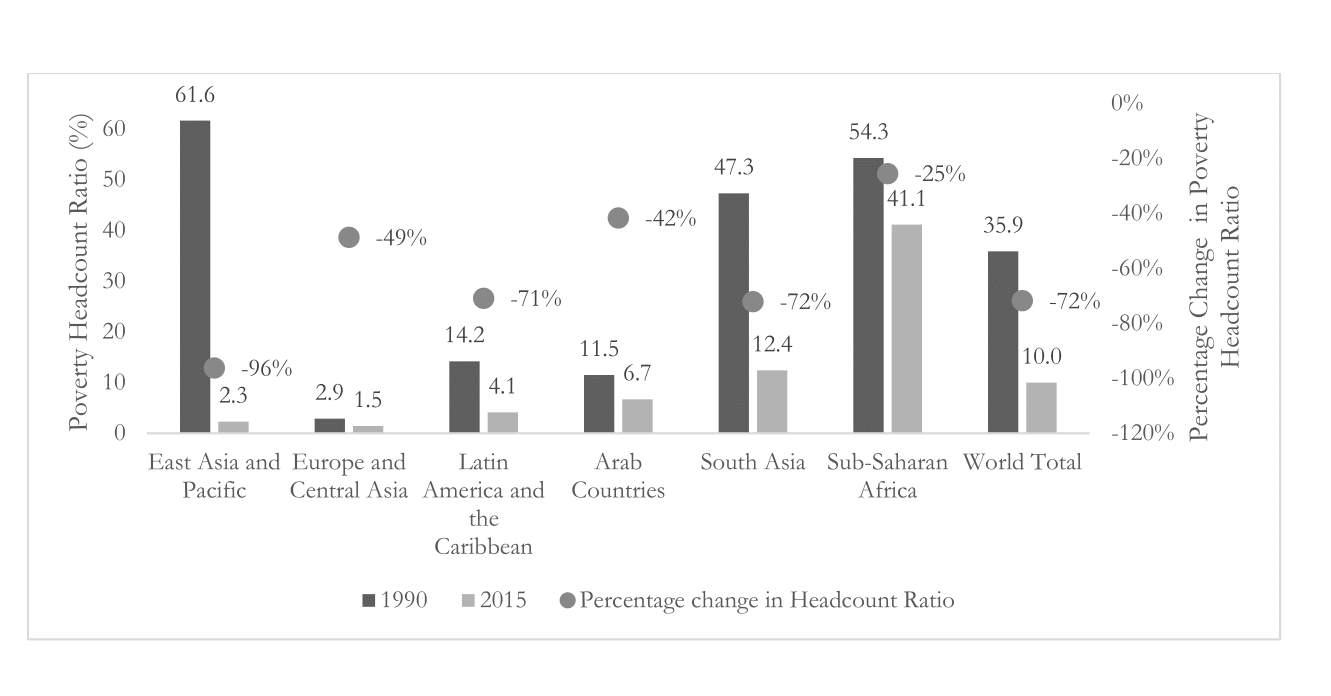

Second, the Arab region fell short of reducing extreme poverty by half from 1990 (the first of the Millennium Development Goals), and it scored the second lowest poverty reduction rate of 42% (after sub-Saharan Africa). The global average for poverty reduction was 72%, mainly driven by the massive fall in extreme poverty in East Asia (led by China) and to a lesser extent in South Asia (see Figure 1).

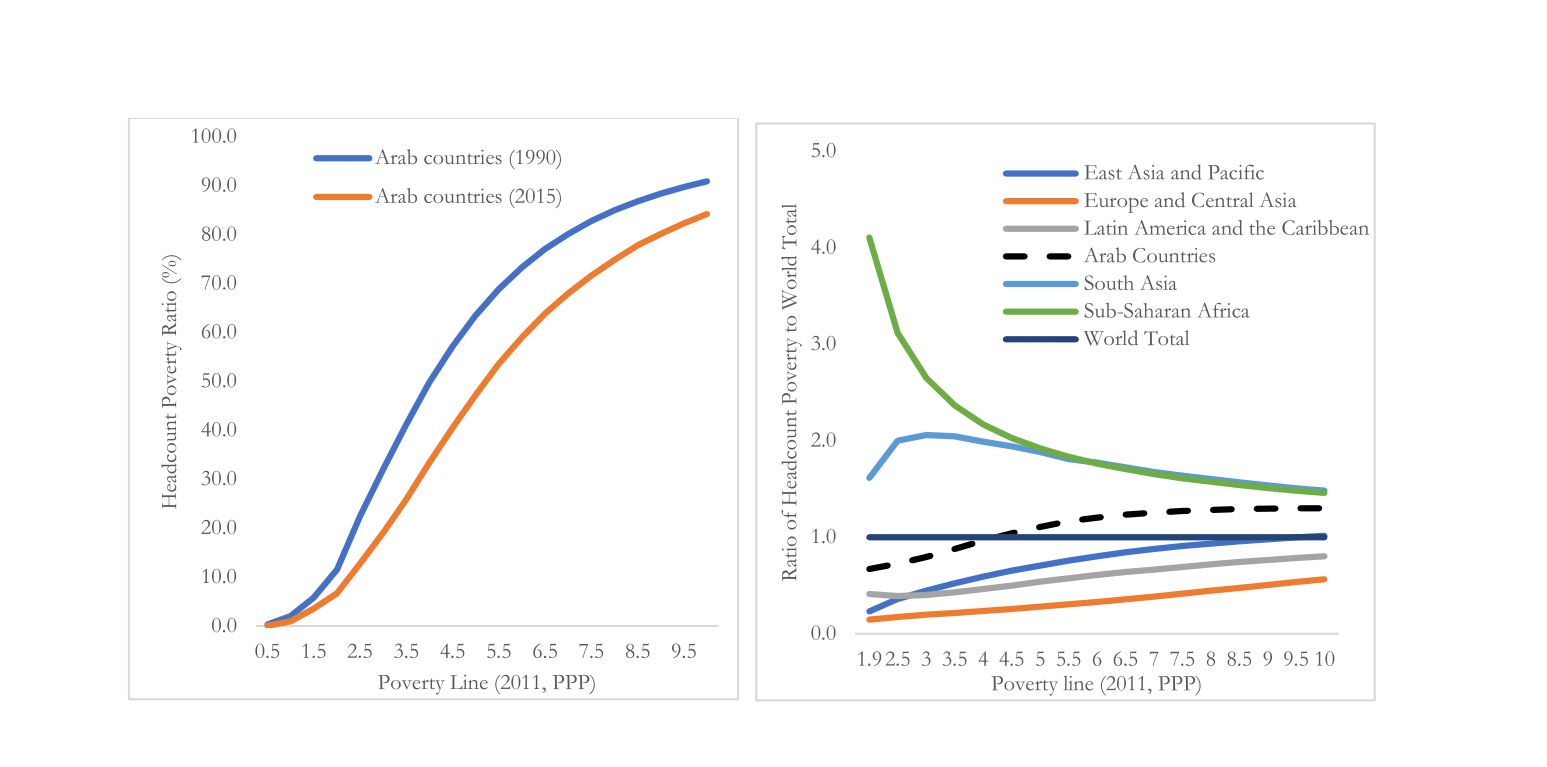

Third, poverty reduction in Arab states took place independently of the choice of the poverty line, as Figure 2A shows. But it is worth noting that as a result of conflicts in some countries, the Arab region is the only one that has witnessed an increase in extreme poverty since 2013, when the $1.9 poverty headcount ratio was approximately 4%. This is an alarming indicator as it signals a new trend of reversing some of the progress in poverty reduction.

Fourth and more importantly, the Arab region’s ranking vis-à-vis the global average varies significantly depending on the choice of the poverty line. Money metric poverty is low using the $1.9 line but not when we move beyond the $3.5 poverty line as the headcount rate for the 11 countries included in the Arab region (Algeria, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen).

Poverty is higher than the global average once we apply higher poverty lines – above $4.0 per day – which are closer to the level of national poverty lines in middle income Arab countries (see Figure 2B).

Multidimensional poverty

The real story emerging from these facts is that although extreme poverty has declined since 1990, vulnerability to poverty is high, and that a significantly higher share of the population in Arab countries is clustered right after the $1.9 per day line compared with other developing regions.

These results are not surprising. They are consistent with recent stylised facts from measures of multidimensional poverty, which focus on deprivation in health, education and living conditions. Examples include deprivation from primary or secondary schooling, infant and child mortality, and deprivation from essential assets and household amenities, such as water and sanitation.

The recent global report on multidimensional poverty by UNDP and OPHI (2018) suggests that nearly one fifth of the Arab region’s population are extremely poor (65 million). Last year, the Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report estimated a total number of multidimensional poor at 116.1 million (40% of the population). It also showed that vulnerability to multidimensional poverty is high, affecting one quarter of the Arab population (ESCWA et al, 2017).

All of this means that nearly one fifth of the Arab population are extremely poor by global definitions, and two thirds are either poor or vulnerable to multidimensional poverty using a regional definition.

Policy implications

There are two policy implications. The first is that we should be concerned with the outlook for poverty. Social and economic policies that affect consumer prices and real household income will matter a great deal in the coming months and years; the latter in particular will have immediate and far-reaching consequences for poverty and vulnerability. Therefore, better and more regular monitoring of Arab poverty is required – for example, through the establishment of a poverty observatory similar to those in China and Latin America.

Second, no matter how good they are, social policies will be insufficient to remedy the problem of Arab poverty. There is a need to understand the root causes of the two factors that are mainly responsible for rising poverty since 2013: rising conflict in some countries; and stagnating or declining household income in middle income and least developed countries.

Key medium-term interventions

Addressing the root causes will establish the foundation for inclusive and sustainable development in the long run. But there are some key interventions to pave the way over the medium term.

The first is that reversing the recent rising trend in extreme monetary poverty (combined with high rates of acute multidimensional poverty and high vulnerability) requires policy-makers to operationalise the principle of ‘first, do no harm’. Doing this demands an assessment of the impact of proposed policy reforms on the poorest and vulnerable, and adopting remedial actions contemporaneously.

Second, it is essential to improve targeting of the poorest – not solely in monetary terms or on a geographical basis but, more importantly, assessing social deprivations and targeting of excluded and vulnerable groups.

Evidence on inequality in the Arab region (to be published soon by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, ESCWA, and ERF) shows that notwithstanding the low average of inequality in the region, national figures mask large disparities in outcomes, as well as opportunities in health, education and living standards among the poorest households in rural areas, those facing high dependency and with an uneducated household head. These groups endure the dynamics of a poverty cycle of low human development, low income and economic exclusion.

Third, breaking this cycle of poverty requires an integrated and equity-focused social and economic programme. The programme needs to be tailored to support the poorest in their efforts to accumulate human capital, and to avert negative coping mechanisms by preparing the poor to integrate and benefit from the returns of the long-term reform and structural transformation.

Fourth, the heightened risk and prolonged nature of conflict (as well as rising environmental concerns in the region) require the development of early warning and emergency preparedness systems to deploy in case of humanitarian crises. This step will help countries like Iraq, which have recently emerged from war, to capitalise on the emergency response system put in place and refined throughout the crises to become an integral part of emergency preparedness within the social protection system.

An evidence-based, systems approach and accountable governance are operational pre-requisites for the successful implementation of the above recommendations as well as longer-term reforms. As a growing number of policy-makers in the region work on reforming social protection, social services and fiscal policies, it is important to engage with the targeted beneficiaries, the poorest and vulnerable, when revisiting these operational domains.

It is also important to recognise that a large part of the evidence used to inform policies is based on poverty profiles and analysis of poverty determinants (‘the problem’) but it says very little about the set of incentives needed and the response behaviours of the poor (‘the solution’) to inform policies.

Going beyond merely reaching the poor with relief to adopting a developmental framework makes it vital to incorporate information on these aspects. This requires the use of participatory approaches and behavioural studies, rather than solely undertaking impact evaluation after years of intervention and assessing ex post successes and failures to break the cycle of poverty.

Further reading

Routledge (forthcoming 2019) Poverty in the MENA in the Handbook of the Middle Eastern Economy, edited by Hassan Hakimian .

ESCWA (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia), United Nations Children’s Fund, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and League of Arab States (2017) Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and OPHI (2018) Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2018: The Most Detailed Picture to Date of the World’s Poorest People.

Figure 1: Headcount poverty ratio at $1.9 (2011 PPP) poverty line, and percentage change from 1990, developing regions, 2015

Source: Calculated from World Bank online Datasets POVCAL.NET

Figure 2:

(A) Headcount poverty ratio at $1.9 to $10 (2011 PPP) poverty lines, Arab states, 1990 and 2015

(B) Ratio of headcount poverty ratio of developing regions to world average, 2015

(A) (B)

Source: Calculated from World Bank online Datasets POVCAL.NET