In a nutshell

Resource-rich countries should save revenue for future usage and adopt spending rules to stabilise the domestic economy.

But the adoption of fiscal spending rules will not necessarily shelter the economy from pro-cyclical fiscal spending.

For MENA countries, there is much to learn from Norway’s experience, both in terms of how to set up a sovereign wealth fund for rainy days and also how to implement a fiscal spending rule more flexibly to avoid pro-cyclical behaviour.

Sound resource management is crucial. There are huge costs associated with large and unpredictable swings in oil prices. If not well managed, the volatility can destabilise the domestic economy and undermine long-term growth. Resource-rich countries are therefore advised to adopt some type of fiscal policy framework (that is, a fiscal spending rule), which, if operated counter-cyclically, should shelter the economy from oil price fluctuations and prevent over-spending on the part of the government.

But the adoption of a fiscal rule does not in itself ensure that fiscal policy works to insulate the domestic economy from oil price fluctuations. In recent research, my colleagues and I show that the constructed fiscal rule may be too lax over the commodity price cycle: the actual conduct of fiscal policy might not be in accordance with the rule or fiscal policy may be conducted differently in booms and busts. Hence, what works in theory may not necessarily work in practice.

Norway’s experience

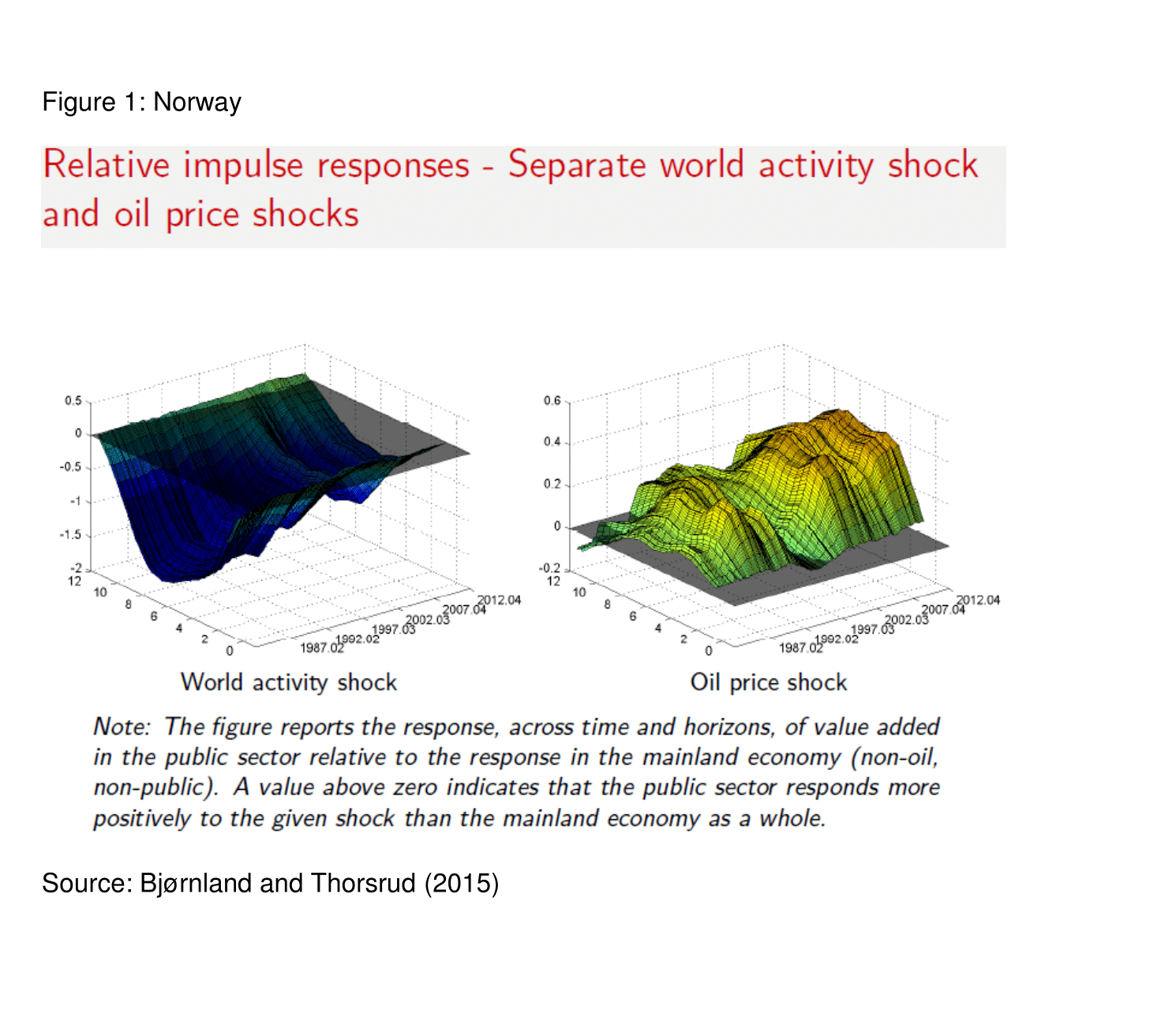

To illustrate the point, in Bjørnland and Thorsrud (2015), we analyse fiscal policy’s response in a resource-rich economy to oil price shocks over time and the extent to which this response has insulated the domestic economy from oil price fluctuations or, conversely, exacerbated their effect.

We focus on Norway, a country where the handling of its petroleum wealth has been described as exemplary. Unlike most oil exporters, Norway has adopted a fiscal framework in 2001, with a view to shielding the fiscal budget, and therefore also the domestic economy, from oil price fluctuations.

In particular, oil and gas revenue is first put in a Savings Fund, of which only the expected real return (4%) of the fund is drawn annually to finance public spending or tax cuts. Thus, in comparing how fiscal policy responds to oil price shocks before and after the rule’s implementation, our study provides a natural experiment for assessing fiscal policy over oil price cycles.

Global demand as a driver of oil prices

Analyses of fiscal pro-cyclicality in oil rich economies come with an important caveat: the price of oil has moved in tandem with global demand in recent decades. Hence, any changes in the response of fiscal policy to the oil price could be due to the role of global demand in the business cycles, and not necessarily the increase in the price of oil.

Thus, and in line with these findings, when analysing fiscal policy responses to oil price shocks, we control for shocks to global activity. Previous studies addressing the role of fiscal policy in resource-rich countries have typically ignored this issue. Furthermore, they have often found that fiscal policy is counter-cyclical in recent commodity booms.

Controlling for global activity, our study confirms that the counter-cyclical fiscal responses found in the recent oil price boom in these previous studies should be attributed to global activity shocks and their domestic propagation, rather than to the adopted fiscal framework (see Figure 1).

In particular, we find that in the wake of supply-driven oil price shocks, fiscal policy is pro-cyclical on impact and over response horizons. If anything, fiscal policy has been more (not less) pro-cyclical since the adoption of the fiscal policy rule in 2001. Hence, taking everything else as given and following an oil price shock, the adoption of the spending rule has not meant that fiscal policy effectively insulates the economy from an oil price shock.

MENA countries

In a more recent study (Bjørnland et al, 2017), rather than first identifying periods of booms and busts and then analysing fiscal policy behaviour in these periods, we identify and analyse fiscal regimes directly. Focusing on the 20 largest oil-exporting countries, many of them in the MENA region, we ask: in which periods is the probability of finding contractionary or expansionary fiscal policy regimes high? And are oil-exporting countries managing their resources well to minimise uncertainty?

We find that government expenditures seem correlated with business cycle fluctuations for many countries, independent of the adopted spending rule. Hence, there is evidence of pro-cyclical behaviour. Furthermore, fiscal policy seems particularly pro-cyclical in the booms. Still, there is large heterogeneity in volatility estimates across countries. Not all the countries are managing their natural resources so as to minimise uncertainty.

Concluding remarks

Although the fiscal rule has not managed to shelter the Norwegian economy from oil price fluctuations, the goal of saving resource revenue for future usage has been accomplished. By only using roughly 4% of the Savings Fund every year, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund is today the largest in the world.

From a policy point of view, the implications of the findings are therefore of general interest since they highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the fiscal framework adopted in a resource-rich economy where the handling of resource wealth has been described as exemplary.

For MENA countries, there is much to learn from the Norwegian experience, both in terms of how to set up a sovereign wealth fund for rainy days and also how to implement a fiscal spending rule more flexibly to avoid pro-cyclical behaviour.

Further reading

Bjørnland, Hilde C., and Leif Anders Thorsrud (2015) ‘Commodity Prices and Fiscal Policy Design: Procyclical Despite a Rule’, Centre for Applied Macro- and Petroleum economics (CAMP) Working Paper No. 5/2015, BI Norwegian Business School.

Bjørnland, Hilde C., Roberto Casarin, Marco Lorusso and Francesco Ravazzolo (2017) ‘Oil and Fiscal Policy: Panel Regime-Switching Country Analysis’, mimeo.