In a nutshell

In MENA, where youth unemployment is high and social media penetration is among the fastest-growing in the world, the internet has fundamentally altered the equation between economic disparity and regime stability.

Social media are engines of social comparison: in unequal MENA economies, where a digital elite may display conspicuous consumption while the young face double-digit unemployment, online platforms raise the visibility of wealth gaps and relative deprivation.

Digital tools lower the costs of coordination: organising a protest used to required logistical resources and faced high risks of state repression; today, encrypted messaging apps and online platforms allow for the rapid mobilisation of dissatisfied citizens.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is currently navigating a period of profound geopolitical tension and domestic fragility. From the continuing fallout of the Gaza conflict to economic stagnation in non-oil economies, the drivers of political instability remain a primary concern for policy-makers.

Traditionally, the debate on what drives civil unrest has focused heavily on economic grievances (Collier and Hoeffler, 2002). It is intuitively appealing to assume that countries with higher income inequality are more prone to revolution, coups and political violence.

Yet empirical evidence has long puzzled economists. Seminal work by scholars such as Fearon and Laitin (2003) and Fearon (2011) famously finds no systematic link between income inequality and the onset of conflict. They argue that grievances are ubiquitous, but that the capacity to organise rebellion is what varies. Similarly, theories on the ‘preconditions’ for revolution often clash with the reality that many highly unequal societies remain remarkably stable for decades.

If inequality alone is the gunpowder, what is the spark? In our recent study (Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2025), we argue that the missing piece of this puzzle is digital connectivity. In MENA, where youth unemployment is high (Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2021) and social media penetration is among the fastest-growing in the world, the internet has fundamentally altered the equation between economic disparity and regime stability.

The digital amplifier

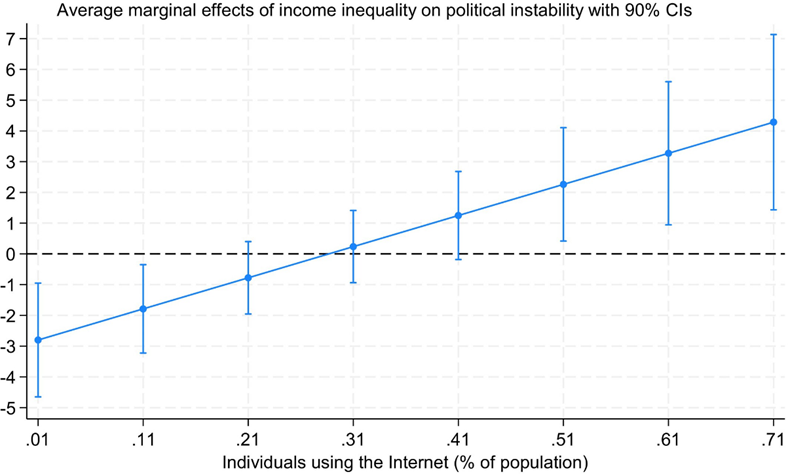

We have analysed data from over 120 countries between 1996 and 2020 to understand how the interaction between income inequality (measured by the Gini index) and internet penetration affects political stability.

Our findings show a conditional relationship that is crucial for understanding MENA’s modern political economy. We find that in countries with low internet penetration, higher income inequality does not lead to higher instability. In fact, in some unconnected societies, high inequality is associated with lower instability. This can be attributed to a lack of political awareness: in disconnected regions, marginalised populations may not be fully aware of the extent of their relative deprivation, or they may lack the logistical means to coordinate collective action.

But this dynamic reverses dramatically as societies become digitally connected. Our results show that once internet penetration exceeds a certain threshold (roughly 50% of the population), it acts as a ‘threat multiplier’ for inequality. In highly connected societies, income inequality becomes a strong and significant predictor of political instability (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Marginal effect of income inequality on instability at different levels of internet usage

Mechanisms: awareness and mobilisation

Why does the internet turn inequality into instability? We identify two primary mechanisms that are particularly relevant to the MENA context.

First, the internet acts as a window into the lives of others, exacerbating relative deprivation. Social media platforms are not neutral; they are engines of social comparison. In unequal MENA economies, where a digital elite may display conspicuous consumption while the young face double-digit unemployment, online platforms heighten the visibility of wealth gaps. As noted by Holmberg (2025), this heightened social comparison fuels frustration and disappointment with the political system. The ‘echo chamber’ effect of social media algorithms further intensifies these radical views.

Second, digital tools lower the costs of coordination. Historically, organising a protest required significant logistical resources and faced high risks of state repression. Today, encrypted messaging apps and social media platforms allow for the rapid mobilisation of dissatisfied citizens.

The region has served as a laboratory for this phenomenon. The ‘Arab Spring’ was an early indicator of how digital tools could help to break the barrier of fear and coordinate mass movements against unequal distributions of power and wealth.

More recently, the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ protests in Iran highlight this mechanism (Farzanegan and Fischer, 2025). As discussed in recent studies (for example, Danesh and Athari, 2024), cyber-activism played a key role in mobilising public opinion and amplifying grievances in the absence of traditional opposition organisations.

Policy implications for MENA

For policy-makers in the region, these findings present a complex challenge. The digital economy is often touted as a solution to the region’s economic woes – a way to modernise education, to diversify away from oil rents and to create jobs for the young (Fardoust and Nabli, 2022). But our research suggests that digitalisation is a double-edged sword.

If governments pursue digital expansion without simultaneously addressing deep-seated economic inequalities, they are effectively building the infrastructure for their own instability. The solution is not to restrict the internet (shutdowns, while common, carry severe economic costs – West, 2016 – and often signal regime weakness) but to view inequality reduction as a national security imperative.

Inequality is a security issue

In the digital age, economic disparity can no longer be hidden. Policies that reduce the Gini coefficient such as progressive taxation, strengthening social safety nets and tackling corruption (which is a significant stabiliser – see Farzanegan and Zamani, 2024) must be prioritised not just for fairness, but also for political stability.

Targeted youth employment

Given that the digital generation is also the demographic most affected by unemployment in MENA, labour market reforms are critical. The combination of idle youth, high inequality and high-speed internet is a volatile mix.

Governance and corruption

Our study confirms that controlling corruption is a significant stabiliser. This finding is particularly critical for the region when viewed alongside earlier research (Farzanegan and Witthuhn, 2017), which demonstrates that the combination of high corruption and a large ‘youth bulge’ significantly increases the risk of conflict.

Today, that youth bulge is hyper-connected. In an era where digital natives can instantly document and share evidence of graft, corruption scandals do not stay local: they go viral. Therefore, improving transparency is not just an administrative goal: it is an essential mechanism to mitigate the specific grievances of a young, digitally connected population.

In conclusion, the ‘digital peace’ is a myth in unequal societies. As MENA continues to come online, the stability of its regimes will depend less on their ability to control information and more on their willingness to close the economic gaps that the internet makes so painfully visible.

Further reading

Collier, P, and A Hoeffler (2002) ‘On the Incidence of Civil War in Africa’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(1): 13-28.

Danesh, A, and SH Athari (2024) ‘Cyber Activism in Iran: A Case Study’, Social Media and Society 10(3).

Fardoust, S, and MK Nabli (2022) ‘Growth, employment, poverty, inequality, and digital transformation in the Arab region: How can the digital economy benefit everyone?’, ERF Policy Research Report No. 45.

Farzanegan, MR, and S Fischer (2025) ‘The Effect of the ‘Woman Life Freedom’ Protests on Life Satisfaction in Iran: Evidence From Survey Data’, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics No. 01-2025.

Farzanegan, MR, and HF Gholipour (2025) ‘Internet, Inequality, and Regime Stability’, Scottish Journal of Political Economy.

Farzanegan, MR, and HF Gholipour (2021) ‘Youth Unemployment and Quality of Education in the MENA: An Empirical Investigation’, in: Ben Ali, MS (ed) Economic Development in the MENA Region: Perspectives on Development in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region, Springer.

Farzanegan, MR, and S Witthuhn (2017) ‘Corruption and political stability: Does the youth bulge matter?’, European Journal of Political Economy 49: 47-70.

Farzanegan, MR, and R Zamani (2024) ‘The Effect of Corruption on Internal Conflict in Iran Using Newspaper Coverage’, Defence and Peace Economics 35(1): 24-43.

Fearon, JD (2011) Governance and Civil War Onset: World Development Report, World Bank.

Fearon, JD, and DD Laitin (2003) ‘Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War’, American Political Science Review 97(1): 75-90.

Holmberg, R (2025) ‘Disappointment Is Not Just a Feeling – It’s a Political Force’, Psyche. West, DM (2016) ‘Internet shutdowns cost countries $2.4 billion last year’, Brookings Institution.