In a nutshell

The middle class has been central to Iran’s economic and political development, evolving from traditional bazaar merchants and mid-ranking clerics to a modern, urban and educated group, which has played a vital role in industrialisation and fuelled entrepreneurship and innovation.

International sanctions on Iran, which intensified from 2012 because of the country’s nuclear programme, have had a significant impact on the country's middle class: an average annual reduction in its size of between 12 and 17 percentage points.

Key transmission channels include reduced real GDP per capita, disrupted merchandise trade, declining investment and industry value added and rising informal employment; these effects highlight sanctions' broader socio-economic costs, underscoring the need for policies that protect middle-class stability.

International sanctions on Iran are likely to become more severe over the coming months. A recent failed resolution in the United Nations (UN) Security Council to continue the sanctions relief on 19 September 2025 has paved the way for the automatic re-imposition of pre-2015 UN sanctions through the ‘snapback’ mechanism triggered by France, Germany and the UK (Amiri, 2025). Amid Iran’s recovery from a devastating 12-day war with Israel in June (Moradi-Lakeh et al, 2025), this development risks deepening the Islamic Republic’s financial crisis and amplifying its socio-economic fallout.

Sanctions affect not only ruling elites but also ordinary people (Sajadi et al. 2024), including the middle class, which is essential for innovation, progress, and socio-economic stability.. In new research, we explore the effect of sanctions on the size of Iran’s middle class and the channels through which it has been affected (Farzanegan and Habibi, 2025).

The why and what of Iran’s middle class

The middle class plays a pivotal role in both the economic and social development of emerging economies. Valued for fostering entrepreneurship, innovation and pro-development norms, it contributes to sustained growth and technological progress (Banerjee and Duflo 2008, Kharas and Gertz 2010, Chun et al. 2017, Pleninger et al. 2022).

Beyond its economic contributions, a sizable middle class stabilises society as a buffer between the conflicting interests of the wealthy and the poor, reducing the risk of political and social conflict (Feng 2003). Understanding its dynamics is therefore essential for assessing both development outcomes and social stability.

In our investigation, we focus on the share of Iran’s middle-class population, defined as individuals in households with daily per capita incomes between $11 and $110 (2011 PPP) (Kharas, 2017). This range captures those who have moved beyond subsistence, possess discretionary income for education, leisure or consumer goods, and are not vulnerable to falling into poverty as a consequence of minor economic shocks. The definition is based on an absolute threshold approach that allows for globally consistent comparisons over time.

The middle class has been central to Iran’s economic and political development, evolving from traditional bazaar merchants and mid-ranking clerics to a modern, urban and educated group shaped by the Pahlavi modernisation and oil wealth of the 1970s (Zahirinejad, 2014; Farzanegan et al, 2021).

The group played a vital role in industrialisation before 1979, in mobilising for the Islamic revolution and later in supporting reformist movements such as Khatami’s presidency, the 2009 Green Movement and the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom protests (Alaedini and Ashrafzadeh, 2016; Farzanegan and Fischer, 2025). Beyond politics, the middle class has fuelled entrepreneurship and innovation in Iran (Sharif, 2015; Bozorgmehr, 2018).

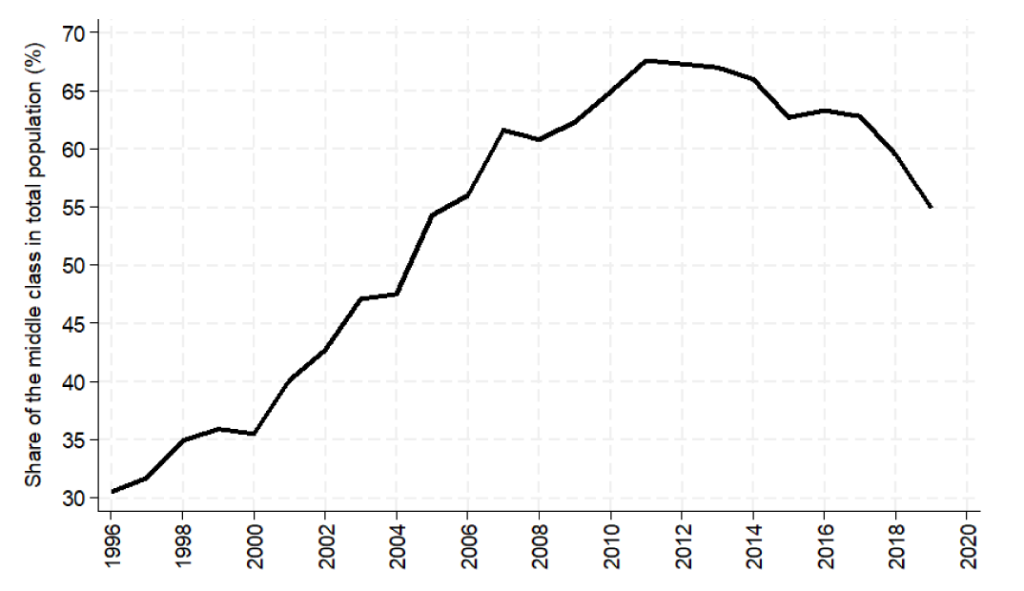

Iran’s middle class expanded steadily from the early 1990s, following the end of the Iran-Iraq war, reaching a significant share of the population by the 2010s (see Figure 1).

This growth was disrupted by severe international economic sanctions starting in 2012. Although the partial relief following the 2016 JCPOA briefly eased pressures (Farzanegan and Batmanghelidj, 2023), the 2018 US withdrawal and the re-imposition of ‘maximum pressure’ sanctions accelerated economic decline and curtailed middle-class expansion. Other domestic factors, such as governance quality and economic policies, may also have influenced these developments. To isolate the impact of sanctions on the middle class, our research uses a counterfactual methodology. The objective is to assess how Iran’s middle class might have evolved in the absence of the sanctions imposed in 2012. This task is complicated by the fact that some of the very socio-economic and political conditions that triggered the sanctions may themselves have shaped subsequent changes in the middle class. The key challenge, therefore, is to construct a synthetic unit that closely mirrors Iran’s trajectory without sanctions, allowing for a meaningful causal comparison.

Figure 1. Iran’s middle class as a percentage of the total population

Methodology and data

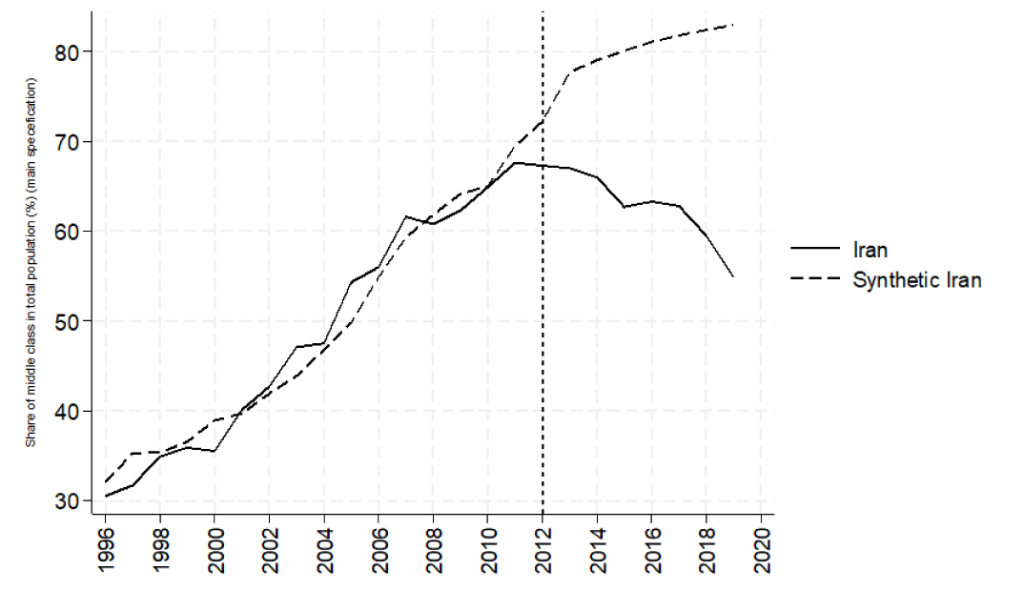

We apply the synthetic control method (SCM) to estimate how sanctions affected Iran’s middle class. SCM constructs a ‘synthetic Iran’ by assigning weights to a group of countries (from MENA, OPEC and selected OIC members) that did not face major sanctions or major conflicts. This synthetic Iran closely replicates Iran’s middle-class trajectory before sanctions (1996-2011).

The treatment year is 2012, when unprecedented sanctions, including oil export embargoes and financial restrictions, were imposed. The difference between actual Iran and synthetic Iran after 2012 shows the effect of sanctions. Importantly, our estimates capture both the direct economic shock of sanctions and the indirect effects of government responses to them.

Our outcome of interest is the size of the middle class, measured as the share of Iran’s population with daily per capita incomes between $11 and $110 (2011 PPP). This absolute definition (Kharas, 2017) ensures that individuals are counted as middle class only if they have moved beyond subsistence, but are not part of the rich elite.

To construct the counterfactual, we include a set of predictors that earlier studies identify as key drivers of middle-class growth and for which data are consistently available across countries in our donor pool (the set of countries with sufficient economic and institutional similarities, from which the set of comparators will be selected). These predictors are:

- Economic development: log real GDP per capita (Penn World Table 10.01).

- Demographics and health: urbanisation, age dependency ratio and life expectancy (World Development Indicators, WDI).

- Education: secondary school enrolment (WDI).

- Resource dependency: natural resource rents as a percentage of GDP (WDI).

- Consumption and government role: household consumption share of GDP and government expenditure share of GDP (Penn World Table 10.01).

- Trade openness: log of merchandise trade (WDI).

- Governance: voice and accountability and control of corruption (WGI).

We also include selected lagged values of the size of the middle class (1996-2010) to strengthen the fit of the synthetic control.

Results

Our donor pool consists of 18 countries from the MENA, OPEC and OIC regions, after excluding those with missing data or affected by wars or sanctions. In the main specification, synthetic Iran is constructed primarily from Tunisia (41.2%), Qatar (21.7%), Malaysia (17.8%), Azerbaijan (12.4%) and Indonesia (6.9%).

Figure 2 compares the size of the middle class between the actual and synthetic Iran between 1996 and 2019. Until 2012, the two trajectories align almost perfectly. But after sanctions, a sharp divergence emerges: while synthetic Iran’s middle class continues to grow, Iran’s declines steeply.

We estimate that sanctions reduced the size of Iran’s middle class by an average of 17 percentage points per year between 2012 and 2019, with the cumulative loss reaching 28 percentage points by 2019. These results suggest that sanctions have pushed lower-middle-class households into poverty and accelerated the downward movement of upper-middle-class groups. Evidence for this is provided for Iran by Salehi-Isfahani (2023). Part of the reduction in the size of the middle class may also be explained by increasing outmigration of skilled labour force. Evidence for the causal effect of sanctions on emigration in a global sample is provided by Gutmann et al (2024). For Iran, Zareei et al. (2024) provide supporting evidence of increased desire to emigrate as migrant workers due to sanctions.

Figure 2. The size of the middle class: Iran versus synthetic Iran

To test the robustness of our results, we conduct in-space and in-time placebo analyses (Abadie et al, 2010, 2015). The placebo tests applied to other countries reveal no comparable divergence, while in-time placebos for Iran in the pre-2012 period also show no spurious effects.

A leave-one-out analysis confirms that the results are not driven by any single donor country contributing to the construction of synthetic Iran. Furthermore, synthetic difference-in-differences estimations (Arkhangelsky et al, 2021) yield average annual reductions of about 10-12 percentage points, broadly consistent with the SCM results. Narrower definitions of the middle class ($10-40/day PPP) produce similar findings.

Potential concerns about spillover effects through oil markets are unlikely, as the synthetic control for main analysis is dominated by diversified economies and evidence shows no sustained global oil price increase from Iran’s reduced supply (Farzanegan and Raeisian Parvari, 2014).

Finally, survey evidence from the World Values Survey corroborates our quantitative results. In 2005, before sanctions, 78.7% of Iranians self-identified as middle-income, compared with only 63.7% in 2020, after years of sanctions. This subjective decline in middle-class identity mirrors the objective contraction revealed in our SCM analysis.

Examining key channels, we find considerable, though approximate, changes in core determinants of middle-class welfare during the period 2012-19. Real income per capita fell by around $3,000, merchandise imports per capita by about 24%, investment per capita by roughly 37% and industry value added per capita by 30%. Exports per capita also dropped by close to 8.5%. Labour market effects include an estimated 3.4 percentage point rise in self-employment and a 2.7 percentage point increase in vulnerable employment (all reported values represent average annual effects for 2012-19).

Conclusion

International sanctions since 2012 have significantly reduced the size of Iran’s middle class, both directly and through adverse effects on income, trade, investment and employment. This erosion reflects the combined impact of external pressure and domestic policy responses, weakening a social group that is vital for stability, cohesion and accountability.

Further reading

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., and Hainmueller, J., 2010. Synthetic Control Methods for Comparative Case Studies: Estimating the Effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105 (490), 493–505.

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., and Hainmueller, J., 2015. Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method. American Journal of Political Science, 59, 495–510.

Alaedini, P. and Ashrafzadeh, H.R., 2016. Iran’s Post-revolutionary Social Justice Agenda and Its Outcomes: Evolution and Determinants of Income Distribution and Middle-Class Size. In: M.R. Farzanegan and P. Alaedini, eds. Economic Welfare and Inequality in Iran: Developments since the Revolution. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 15–45.

Amiri, F., 2025. UN Security Council votes against lifting Iran ‘snapback’ sanctions ahead of deadline.

Arkhangelsky, D., Athey, S., Hirshberg, D.A., Imbens, G.W., and Wager, S., 2021. Synthetic Difference-in-Differences. American Economic Review, 111 (12), 4088–4118.

Banerjee, A.V. and Duflo, E., 2008. What Is Middle Class about the Middle Classes around the World? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22 (2), 3–28.

Bozorgmehr, N., 2018. Start-up republic: can Iran’s booming tech sector thrive? [online]. Financial Times. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/ca7ab580-3d71-11e8-b9f9-de94fa33a81e [Accessed 3 Apr 2025].

Chun, N., Hasan, R., Rahman, M.H., and Ulubaşoğlu, M.A., 2017. The Role of Middle Class in Economic Development: What Do Cross-Country Data Show? Review of Development Economics, 21 (2), 404–424.

Farzanegan, M.R., Alaedini, P., Azizimehr, K., and Habibpour, M.M., 2021. Effect of oil revenues on size and income of Iranian middle class. Middle East Development Journal, 13 (1), 27–58.

Farzanegan, M.R. and Batmanghelidj, E., 2023. Understanding Economic Sanctions on Iran: A Survey. The Economists’ Voice, 20, 197–226.

Farzanegan, M.R. and Fischer, S., 2025. The effect of the ‘woman life freedom’ protests on life satisfaction in Iran: Evidence from survey data. Marburg, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics No. 01–2025.

Farzanegan, M.R. and Habibi, N., 2025. The effect of international sanctions on the size of the middle class in Iran. European Journal of Political Economy, 90, 102749.

Farzanegan, M.R. and Raeisian Parvari, M., 2014. Iranian-Oil-Free Zone and international oil prices. Energy Economics, 45, 364–372.

Feng, Y., 2003. Democracy, Governance, and Economic Performance: Theory and Evidence. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Gutmann, J., Langer, P., and Neuenkirch, M., 2024. International sanctions and emigration. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 226, 106709.

Kharas, H., 2017. The unprecedented expansion of the global middle class. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, Global Economy & Development Working Paper No. 100.

Kharas, H. and Gertz, G., 2010. The New Global Middle Class: A Cross-Over from West to East. In: C. Li, ed. China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Moradi-Lakeh, M., Majdzadeh, R., Farzanegan, M.R., and Naghavi, M., 2025. Iran and beyond: perilous threats to population health. The Lancet, 406, 1001–1002.

Pleninger, R., de Haan, J., and Sturm, J.-E., 2022. The ‘Forgotten’ middle class: An analysis of the effects of globalisation. The World Economy, 45 (1), 76–110.

Sajadi, H.S., Farzanegan, M.R., and Majdzadeh, R., 2024. WHO EMRO’s initiative on economic sanctions: delayed but promising. The Lancet, 404 (10463), 1638–1639.

Salehi-Isfahani, D., 2023. The impact of sanctions on household welfare and employment in Iran. Middle East Development Journal, 15, 189–221.

Sharif, H., 2015. Iran’s digital start-ups signal changing times [online]. BBC News. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-34458898 [Accessed 3 Apr 2025].

Zahirinejad, M., 2014. The State and the Rise of the Middle Class in Iran. Hemispheres. Studies on Cultures and Societies, 29 (1), 63–79.

Zareei, A., Falahi, M.A., Wadensjö, E., and Sadati, S.M., 2024. International Sanctions and Labor Emigration: A Case Study of Iran. Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), IZA Discussion Papers No. 17062.