In a nutshell

Growth in MENA is expected to increase modestly from an average of 1.8% in 2023 to 2.2% in 2024; this acceleration is primarily driven by high-income oil exporters, while growth is expected to decelerate in developing MENA countries; Gaza’s economy has come to a near-total halt.

Peace is an essential precondition for sustained economic growth, as conflicts can undo decades of progress and delay development by generations; without conflict, income per capita in conflict-affected countries in MENA could have been, on average, 45% higher.

The region could boost growth through better allocation of talent in the labour market, leveraging its strategic location, and promoting innovation; closing the gender employment gap, rethinking the public sector and facilitating technology transfers through trade are also key.

Over the last 50 years, average per capita income in MENA countries has increased by just 62%. In comparison, over the same period, the increase was fourfold in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) as a whole and twofold in advanced economies.

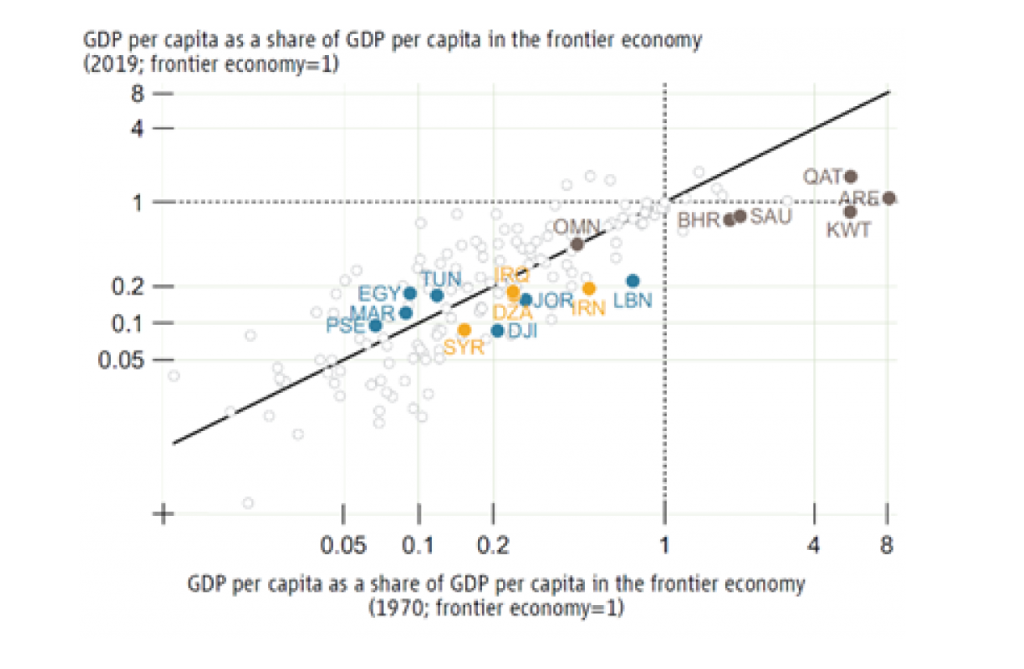

Only Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and the West Bank and Gaza (before the current conflict) have come somewhat closer to the income levels at the frontier (the most advanced economy), while the remaining MENA developing economies have lagged further behind (see Figure 1). GDP per capita in the region, including the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), averages only 25% of the level of the frontier.

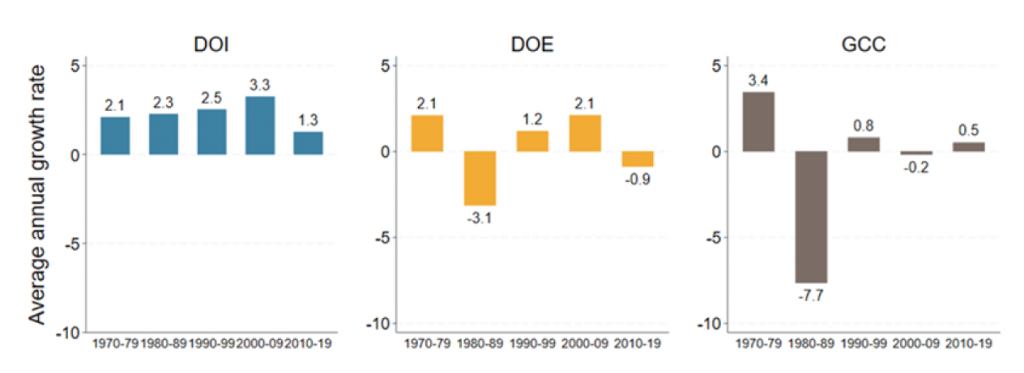

To narrow this gap to half the level of GDP per capita at the frontier, the region would need to grow at an average of 3.8% a year in per capita terms over the next three decades. But growth in income per capita among MENA oil importers has slowed dramatically – from 3.3% in the 2000s to 1.3% a year between 2010 and 2019 – while growth in both the GCC countries and the developing oil exporters is highly volatile (see Figure 2).

The World Bank’s October 2024 MENA Economic Update looks at economic growth from four complementary perspectives:

- The short-term outlook.

- The economic consequences of the conflict in Gaza.

- The long-term growth impact of conflicts in MENA.

- Opportunities to boost growth in the region.

Figure 1: Distance to the frontier in MENA countries: 1970 and 2019

Figure 2: Average annual growth rates in MENA country groups (1970 to 2019)

Note: DZA = Algeria. BHR = Bahrain. DJI = Djibouti. EGY = Arab Republic of Egypt. IRQ = Iraq. IRN = Islamic Republic of Iran. JOR = Jordan. KWT= Kuwait. LBN = Lebanon. MAR = Morocco. OMN = Oman. QAT = Qatar. SAU = Saudi Arabia. SYR = Syrian Arab Republic. TUN = Tunisia. YEM = Republic of Yemen. PSE = The West Bank and Gaza. ARE = United Arab Emirates. DOI = developing oil importers (Djibouti, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, The West Bank and Gaza). DOE = developing oil exporters (Algeria, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic, and the Republic of Yemen). GCC = Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). In the top panel, GDP per capita in both years is a share of GDP per capita in the US. Countries above the line reduced the gap in GDP per capita with the United States (the frontier economy) between 1970 and 2019. Both axes are in log scale. Different colors are used for the different MENA country groups. In the bottom panel, the bar graph reports average annual growth rates in income per capita for the three country groups in the MENA region, by decade. Aggregate GDP for each country is obtained by applying growth rates from national accounts to the level of GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2017—the growth rate from real GDP at constant (2017) national prices is applied to the expenditure side real GDP level at chained PPPs in 2017. Per capita GDP in each group is the sum of aggregate GDP across countries within the group divided by the sum of the population for each group.

Fragile growth

Real GDP growth in MENA is expected to show a modest increase from 1.8% in 2023 to 2.2% in 2024. This uptick masks important disparities within the region. It is driven by the GCC countries, where growth is forecast to rise from 0.5% in 2023 to 1.9% in 2024.

Growth is expected to decelerate in the whole of developing MENA. In developing oil importers, it will decelerate from 3.2% in 2023 to 2.1% in 2024, as the repercussions of the current conflict spill over directly onto some countries and exacerbate pre-existing vulnerabilities in others. Real GDP growth in developing oil exporters will decline from 3.2% in 2023 to 2.7% in 2024.

In per capita terms, the region is projected to grow by 0.9% in 2024, up from 0.5% in 2023. Changes in GDP per capita are influenced by both aggregate GDP and population changes. However, this growth rate remains significantly lower than the 3.8% real GDP per capita growth needed to reach halfway to the frontier over the next 30 years.

Over the past year, MENA’s 2024 real GDP growth forecasts have also been substantially downgraded, with the largest revisions being among economies in fragile and conflict-affected situations. These downgrades partly reflect the extension of OPEC+ oil production cuts and increased uncertainty due to the conflict centred in Gaza.

Forecast dispersion among private sector forecasters, a measure of uncertainty, is high and increasing in MENA. Since the outbreak of the conflict in October 2023, uncertainty in MENA has risen and remained elevated, while uncertainty has dropped in other EMDEs. As of September 2024, uncertainty in one-year-ahead real GDP growth forecasts in MENA is nearly twice as high as in other EMDEs.

The economic consequences of the conflict centred in Gaza

Amid a deepening humanitarian crisis, Gaza’s economy has come to a near-total halt, with a staggering 86% contraction in the second quarter of 2024. In the West Bank, the economy also contracted by 23% in the second quarter, largely due to tighter restrictions on movement, a decrease in permits for Palestinians working in Israel, and a severe fiscal crisis. As a result of increased deductions by Israel on the clearance revenue transfers and reduced domestic tax receipts, the Palestinian Authority is facing a projected financing gap of US$1.86 billion in 2024, more than double that of 2023.

In neighbouring economies, the conflict has suppressed economic activity. Tourism receipts have fallen (for example, there has been a 6.6% decrease in tourist arrivals in Jordan in the year to August 2024), as have fiscal revenues (for example, there has been a 62% drop in Suez Canal revenues in Egypt in the first half of 2024 relative to the second half of 2023).

As the latest MENA Economic Update was going to print, the escalation of the conflict in Lebanon is causing increasing human and economic tolls. The full extent of the impact of these escalations on Lebanon and the region will be shaped by the future trajectory of the conflict.

Globally, energy and financial markets have so far shown resilience. Despite some early, short-term fluctuations, spot oil prices and oil futures have fallen considerably since October 2023 amid robust supply and concerns about sluggish demand.

Disruptions in maritime transport, especially through the Suez Canal, have increased shipping times and spot prices, with freight rates rising four- to fivefold by August 2024 compared with November 2023. But with low global demand, increasing fleet sizes and contractual price stickiness, the increase in shipping costs has not as yet been passed through to consumers.

The long shadow of conflict in MENA

The conflict centred in Gaza underscores a wider trend of increasing violence in the region. There has been more than a twofold increase in conflict episodes and a sixfold increase in MENA’s share of global fatalities since the 1990s.

The cost of conflict transcends what common economic indicators can measure. Yet conflicts certainly lead to immediate economic losses and can have long-term detrimental effects on development. These outcomes stem from human capital losses, forced displacement, the destruction of physical infrastructure, and various forms of economic disorganisation, including supply chain disruptions.

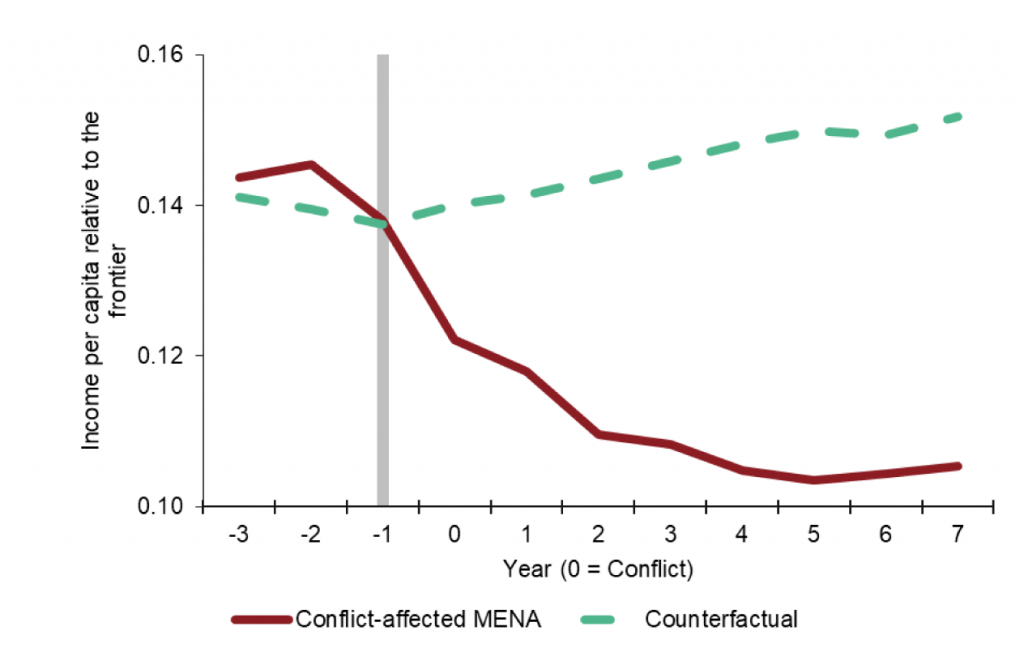

Analysis in the latest MENA Economic Update, using a synthetic control method, shows that income per capita in conflict-affected countries in MENA could have been, on average, 45% higher without conflict, measured seven years after its onset (see Figure 3). This loss is equivalent to 35 years’ worth of progress in the region.

Peace is an essential pre-condition for sustained economic development as persistent conflict can undo decades of progress, setting back countries in achieving sustainable development.

Figure 3: Counterfactual estimates of income per capita relative to the frontier for MENA countries in conflict

Prospects for a more prosperous region

Despite the region’s current challenges, there is significant untapped potential in MENA. Increasing employment rates and enhancing aggregate productivity are key levers for boosting standards of living in the region. Low employment rates and low levels of aggregate productivity together explain 60-80% of the difference in standards of living between MENA countries and the frontier.

This suggests that countries can allocate their labour market talent more effectively and leverage their strategic location to boost innovation and sustain growth. In particular, the latest MENA Economic Update emphasises the need to close gender employment gaps and boost productivity through a reallocation of talent from the public sector to the private sector, alongside an increase in international trade to tap the frontier of knowledge and technology.

Talent misallocation, both in and out of the labour force and between the public and private sectors, has harmed living standards in the region. Over the past 50 years, schooling in MENA has rapidly increased, especially for women, but women’s labour force participation rates have stagnated. MENA exhibits the lowest rates of women’s labour force participation in the world (19% on average compared with a 28% average for South Asia, which is the second lowest). Closing gender employment gaps in MENA would result in a 51% increase in per capita income in the typical MENA country.

Moreover, the public sector may be pulling too much talent away from the private sector, without translating into better public goods and services. Countries can exhibit low aggregate productivity when resources such as capital and labour are not being put to their best use.

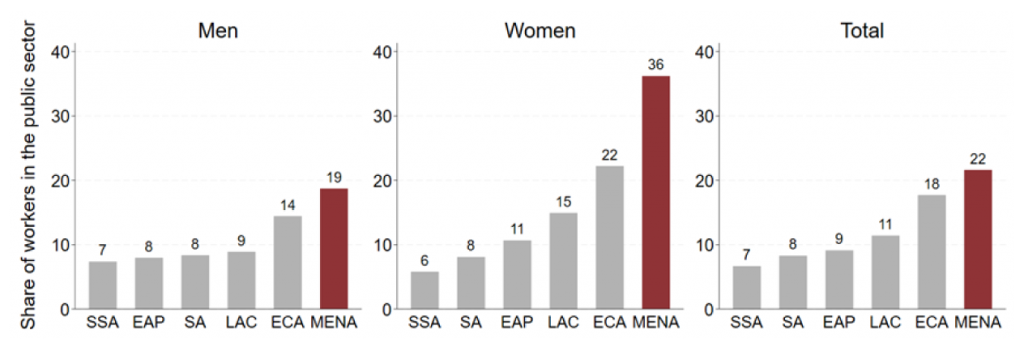

In MENA, a potential source of talent misallocation is the markedly high share of public sector employment compared with the rest of the world, especially for women. On average, 19% of employed men and 37% of employed women work in the public sector in MENA (see Figure 4). The average share of employed women in the public sector in MENA is almost twice that of Europe and Central Asia – the region with the second largest share of employed women in the public sector.

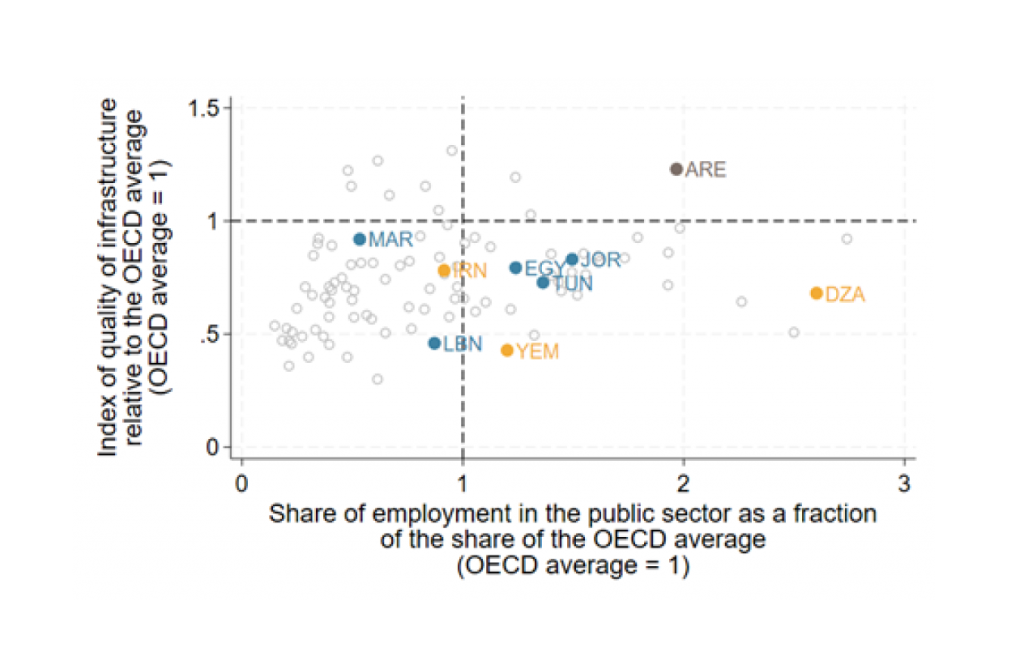

The size of the public sector in MENA might be too large relative to the quality of public goods and services delivered, and it might be taking too much talent from the private sector. Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia and Yemen, for example, have a higher share of public sector employment than the OECD average, yet they exhibit a lower quality of overall infrastructure (see Figure 5).

In MENA, a higher share of public sector employment does not necessarily correspond to better quality infrastructure than the OECD average. Transforming the size of the state would lead to substantial gains in aggregate productivity. If labour were to be optimally reallocated from the public sector to the private sector, aggregate productivity would increase by 5% in Iran, 8% in Tunisia and Egypt, 9% in Jordan, 43% in Algeria and 46% in Iraq.

Figure 4: Share of employment in the public sector

Figure 5: Quality of infrastructure and size of the public sector

Note: In the top panel, the bar chart reports the percentage of employed men (left panel) and women (middle panel) that are employed in the public sector. The figure shows the weighted average of employment in the public sector for each region. The data are for the latest year available for each country. MENA countries included in the average are the following: the Arab Republic of Egypt, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, the West Bank and Gaza. MENA = Middle East North Africa. SSA = sub-Saharan Africa. EAP = East Asia and Pacific. SA = South Asia. LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean. ECA = Europe and central Asia. In the bottom panel, YEM = Republic of Yemen. LBN = Lebanon.

Finally, to promote further productivity gains, MENA countries could leverage their location to access frontier knowledge and technology through increased international trade. Low aggregate productivity also reflects production techniques (ideas, technology) at the firm level that are far less advanced than those in the frontier economy.

For MENA, the knowledge produced in the region lags both in its impact and its novelty – which suggests that lags in technology sophistication are a potential source of the low levels of residual aggregate productivity (what’s known as total factor productivity or TFP). Over the past 15 years, Saudi Arabia is the only MENA country to produce a significant increase in the novelty and impact of its knowledge – but it remains well behind the frontier.

More international trade is another critical lever to boost aggregate productivity via the knowledge and technology spillovers that accompany exporting and importing. The MENA region is not competitive in non-oil exports – as a result of implicit barriers to exports – despite a natural competitive advantage from its proximity to the European Union. Some MENA developing economies are among the 20 economies least open to exports out of a group of 195 countries. Improving data quality and transparency in the region would help to remove bottlenecks for technology diffusion and to facilitate more and better circulation of ideas.

MENA has a long way to go – but the region also has large windows of opportunity.