In a nutshell

A productive future cannot be based on non-renewable energy: MENA countries that depend on production of such energy sources have much lower labour productivity growth rates than those that rely on more diversified production structures.

Capitalising on the transition to renewable energy requires a number of linked initiatives: embracing global electrification; taking advantage of proximity to solar and wind power sources; keeping the cost of capital low; managing technological risks; and exploring carbon prices and carbon sinks in their deserts.

MENA countries can liberate their future from the unsustainable past, diversify their economies, re-purpose their fossil deposits and create new productive and clean activities – or remain locked into non-renewable activities with an uncertain future and damaging consequences for themselves and the globe.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has rich natural endowments of high solar radiation over much of the year and multiple locations with strong winds. The solar potential per square kilometre is equivalent to energy produced by between one and two million barrels of oil annually. This alone means that the region’s solar energy producers could meet at least 50% of global electricity demand. Furthermore, three-quarters of MENA countries have average wind speeds that exceed the minimum threshold for utility-scale wind farms.

All of this suggests that the region has an inherent comparative advantage in the development of renewable energy sources, a transition that would help to reduce emissions of the greenhouse gases that cause climate change. The region’s contribution to global emissions is put at less than 8.7% (World Bank Group, 2023).

The transition is a huge opportunity for the region to implement transformative programmes that would help energy producers and consumers to rebase their economies and societies, anchoring them on productive activities, and spurring sustainable development and inclusive growth.

The following opportunities could be realised:

- Diversifying MENA countries’ lopsided economies, extricating them from the damaging negative consequences of the rentier structures that their dependence on fossil fuels has engendered.

- Availing themselves of the large employment opportunities that this transition will offer.

- Exploiting the chance to address the prevailing damaging inequities of income and wealth distributions.

- Promoting an inclusive growth strategy and giving women, young people and marginalised communities a better chance to benefit from, participate in and lead the development of the economy and society.

- Rebasing their economies on renewable assets and factors of production, and anchoring them on a promising future of new, sustainable, clean and productive comparative advantages and exports.

- Invigorating the private sector, particularly empowering MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) to lead the transition, to adopt the most appropriate technologies, to supply energy sources to underserved regions and to innovate and develop local capacities and skills that can expedite the transition and increase its speed, depth and benefits.

- Capitalising on the opportunity to reduce overblown public sectors and heavy-handed government interventions, and giving a more balanced role to the private sector.

MSMEs in the region are emerging as the agents of change that can best lead the transition to a cleaner and sustainable future (see Saif and Awad, 2024). Given their widespread geographical distribution, they are well positioned to contribute to a more decentralised, secure and resilient energy system. By engaging in decentralised energy production and storage, MSMEs can support the region’s green energy transition and also reduce their operational costs and carbon footprint.

Large-scale energy projects are often constrained by the national grid’s capacity and spread. In contrast, decentralised renewable energy systems anchored on MSMEs allow energy generation closer to consumption nodes, thereby reaching underserved regions, reducing transmission losses, enhancing efficiency, exploiting cheaper and cleaner energy alternatives, and improving the competitive advantage of the economy.

Renewable energy is now the cheapest power option in most parts of the world, particularly in MENA. Prices of renewable energy technologies are dropping very rapidly. The cost of electricity from solar power fell by 85% between 2010 and 2020. as the cost of solar panels fell commensurately.

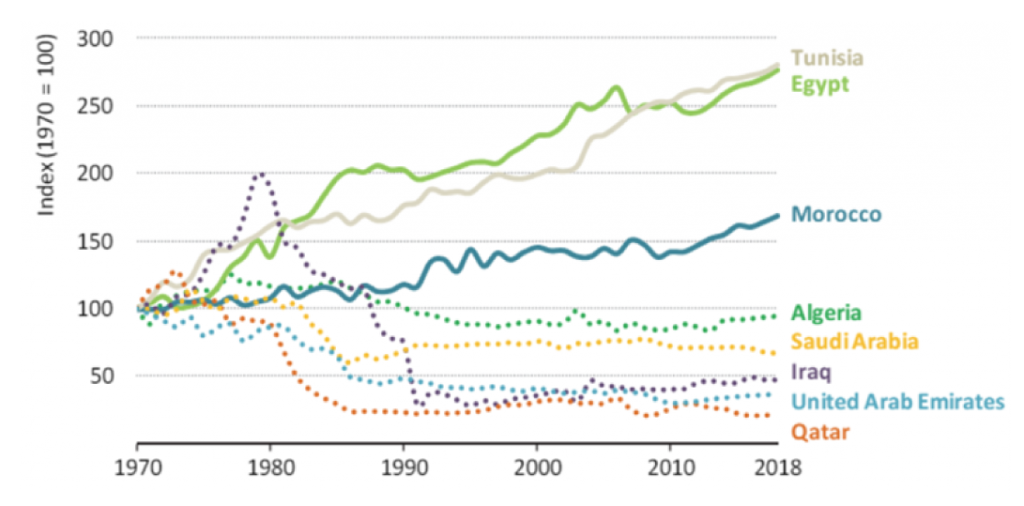

Figure 1: Labour productivity changes in the MENA countries, 1970-2018

More importantly, a productive future cannot be based on non-renewable energy. MENA countries that depend on non-renewable energy production have much lower labour productivity growth rates than those that rely on more diversified production structures (see Figure 1).

The factors described above constitute necessary conditions, but they are not sufficient. While they highlight the potential, there are a few conditions and policies that need to be developed to guide the transition and to cement it on firm foundations that make it possible to reap the full benefits.

The Hausmann view on what it takes to capitalise on the transition to renewable energy

Some economists have considered the benefits and risks of capitalising on transition strategies to renewable energy and even the broader context of making the transition to a green economy. But two economists in particular have focused their attention on MENA’s potential to reap the benefits of an effective transition: Ricardo Hausmann and Paul Collier. (Here we focus on the former; the contribution of the latter will be discussed in a later column.)

In one seminal contribution, Hausmann (2022) argues that it would be a grave mistake for developing countries not to consider climate change as an important aspect of their development strategies. This is because climate change disasters are already imposing a heavy toll on the global economy, and many countries are recognising that the world must slash emissions to prevent a climate catastrophe.

More importantly in his view is the realisation that decarbonisation will usher in several structural changes that will present new opportunities and threats as the demand for dirty goods and services declines and the demand for those that are cleaner and greener increases. This realisation will raise the question as to how countries, particularly developing ones in the MENA region, can supercharge their development by breaking into fast-growing industries that will help the world to reduce its emissions and reach net zero, and offer greater employment opportunities and new export lines.

Drawing on the experience of successful Southeast Asian economies, Hausmann points out that these countries have sustained decades of high growth by upgrading their areas of comparative advantage, from garments to electronics to machinery and chemicals. They did not remain stuck in industries bequeathed by the past. Developing countries, including in MENA, can create jobs that pay higher wages, but they have to find new industries that can grow and export competitively even with higher wages.

At its core, making the transition to a green economy with green energy will create new opportunities – especially for those that move fast. The paths that are opening up have not been trodden by many predecessors. The transition will require significant greenfield investments, and plants will have to find new places to locate.

This could be a great opportunity for MENA countries with their solar endowments and huge spatial deserts that are scarcely inhabited. But to access it, they must understand the changing landscape, leverage their existing comparative advantages and, more importantly, develop new ones.

Embrace global electrification

The future is likely to demand that the energy used in mining be green, especially since mining is energy-intensive and has local environmental impacts. It is also water-intensive, something that is in short supply in most MENA countries unless green energy is used in desalination. Most countries fail to implement a regime that is open to investment but adequately manages these risks and conflicts of interest.

In addition, minerals must be processed into the capital goods needed by the electrification process. This involves long manufacturing global value chains. Today, many mega-factories are being built to produce lithium-ion batteries, mostly in China, Europe and the United States. A good question to ask is why none are being developed in MENA countries. The region must develop what it takes to host them. If not, countries must acquire the missing capabilities and resources.

Capitalise on proximity to renewable energy

The sun shines and the wind blows in many countries, but some in MENA are blessed with abundant opportunities and endowments that few regions can match. In addition, oil and coal products are incredibly energy-dense, meaning that they contain a lot of energy per unit of weight and volume, making them cheap to transport.

For example, it costs less than $4 to ship a barrel of oil that is worth about $100 at the well halfway around the world. As a consequence, oil and coal made the world flat from an energy perspective. Fossil fuel-poor countries could become competitive in energy-intensive products. China, Japan, and Germany, for example, are major steel exporters but energy importers.

This is unlikely to be the case with the alternatives to oil. Thus, countries with a lot of sunshine produce solar energy for less than $ 20 a megawatt hour, but to move the energy a long distance, it must be stored in a molecule such as ammonia. This conversion will increase the cost of energy six-fold (not including the cost of transport). This creates enormous incentives to use renewable energy in situ. Energy-intensive industries will be likely to move toward places rich in green energy. This will make the MENA region a desirable hub for energy-intensive production.

Keep the cost of capital low

Hausmann notes that most of the cost of renewable energy production is the fixed cost of the equipment, including the cost of the capital to buy it. Germany may be able to obtain funding at a cost of 2%, while in Morocco, it may be 7%. Therefore, although Morocco is sunnier than Germany, this does not translate into cheaper solar energy.

This is a major issue because the sun is strong in the Middle East, but capital markets shun these regions, potentially reversing their comparative advantage. Good institutions[1] and macroeconomic management that keep country risk low are critical determinants of the cost of capital and hence the ability of MENA countries to be competitive in green energy.

Manage technological risks

Technological uncertainty is a defining characteristic of the world today. One megawatt hour of solar energy when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing is cheaper than the fossil fuel needed to generate the same megawatt hour using a thermal plant. This was unthinkable a decade ago (Chrobak, 2021).

At this time, it is difficult to predict which technologies will win the race: there are many in the running. MENA countries should be aware of the bets being placed across the world. While technological surveillance is done regularly by industry, few governments do enough of it.

Explore carbon sinks – net zero is not gross zero

A few countries in the MENA region have not adopted carbon prices in an appropriate manner and a few do not even price carbon (Saudi Arabia, for example). The region does not have large forests, but they have large empty deserts, and it is imperative that they find ways to benefit from carbon sinks.It may be worthwhile to consider leasing these to create the credible offsets needed to prolong the life of their huge deposits of fossil fuels as an interim strategy.

There are; however, other sinks too. There may be geological formations in the deserts that could be ideal for storing carbon that has been captured. MENA countries should figure out where these are and certify that they are safe and sealed. Property rights must be defined on these geological formations so that investment can take place and countries in the region can collect rent from storage space.

The Hausmann recipe is carefully laid out for the MENA countries to follow. They can liberate their future from the unsustainable past, diversify their economies and create new productive and clean activities – or remain locked into non-renewable activities with an uncertain future and damaging consequences for themselves and the globe.

Further reading

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. London: Profile Books Ltd.

Chrobak, Ula (2021) ‘Solar Power Got Cheap. So Why Aren’t We Using It More?’, Popular Science.

Hausmann, Ricardo (2022) ‘Green Growth Opportunities’, Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund.

Saif, Ibrahim, and Ahmad Awad (2024) ‘In the Context of the Renewable Energy Transition in MENA: The Role of MSMEs in Fostering Inclusive, Equitable, and Sustainable Economic Growth – Jordan Case Study’, ERF Policy Research Report No. 50.

World Bank Group (2023) Middle East and North Africa Climate Roadmap (2021-2025).

[1] Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Profile Books Ltd.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.