In a nutshell

Analysis of freedom to express opinions in Arab countries highlights persistent challenges and areas of improvement; while countries like Kuwait and Tunisia maintain their relatively high rankings, others, such as Egypt and Sudan, continue to face significant limitations.

As these countries navigate their respective political and social landscapes, policy-makers must focus not only on removing legal restrictions but also on fostering environments where diverse opinions can be expressed without fear of reprisal or self-censorship.

Moving forward, a deeper understanding of how freedom intersects with other dimensions of wellbeing will be essential for designing more comprehensive development strategies that prioritise human agency and social progress.

Freedom is a fundamental dimension of human wellbeing, yet it is consistently overlooked in assessments of inequality, poverty and multidimensional wellbeing worldwide. These analyses often focus on other critical dimensions, such as income, education and health, but political philosophy has long emphasised the importance of freedom in shaping a meaningful life.

For example, in Nozick’s libertarian philosophy, freedom and self-ownership are central to the concept of procedural justice (see Nozick, 1974), while Rawls’s theory of justice places liberty as a primary principle ahead of other considerations (see Rawls, 1971). Sen’s capability approach also highlights the centrality of freedom in expanding an individual’s ability to choose and achieve valuable social functionings (see Sen, 2010). Similarly, analytical Marxists view effective freedoms as essential to achieving equality of opportunity (see Cohen, 2009).

Freedom and justice have long been intertwined, an idea that traces back centuries. The Arab philosopher Ibn Khaldun emphasised the crucial relationship between justice and governance in his Muqaddimah. Although he did not directly address freedom in the modern sense, his work highlights the importance of freedom from oppression and expropriation as essential for a prosperous society. Ibn Khaldun argued that just governance prevents instability and fosters long-term prosperity, a concept that remains relevant today as contemporary discussions on human development increasingly recognise the importance of justice and freedom.

Enhancing individual freedoms should be central to any development policy, as it is a crucial element of fostering human wellbeing and ensuring meaningful participation in society. But understanding how freedom contributes to social welfare requires a context-sensitive approach that accounts for local realities.

Freedom to express opinions

This column focuses on one particularly pertinent dimension of freedom: the freedom to express opinions. While some countries face extreme government restrictions on this front, the reality in the Arab world is more nuanced. It is not a simple binary between total repression and absolute freedom; rather, it involves a range of subtle constraints shaped by both government policies and unwritten social norms.

This is not a challenge exclusive to the Arab world. Consider the shifting dynamics of freedom to express opinions in countries often considered free. In these contexts, individuals may once have felt entirely at liberty to express their opinions. But this sense of freedom may have become constrained over time, not necessarily by government policies but by evolving social pressures, particularly on social media.

Public discourse on these platforms is increasingly influenced by vocal groups, creating an environment where opinions are scrutinised intensely. As a result, many people, wary of misinterpretation or backlash, opt for self-censorship. While this might appear voluntary, it highlights how social norms can significantly restrict effective freedom, even in formally free societies.

Thus, the freedom to express opinions is shaped by both formal laws and informal social dynamics, fluctuating with the changing cultural context, particularly in the age of social media.

This example underscores a crucial policy implication: promoting freedom of expression is not solely about lifting government restrictions. It also involves creating a social environment that empowers people to express their opinions effectively. For countries looking to enhance freedom within their development frameworks, a balanced approach that considers both institutional and social dimensions is not just important but essential.

Data from the Arab Barometer

Here, I analyse data from Waves III and VII of the Arab Barometer to track changes in the perceived freedom to express opinions in Arab countries over the past decade.

The majority of countries in Wave III were surveyed in 2013, although some data were collected as early as December 2012 (partially in Jordan and fully in Palestine) and as late as 2014 (Morocco, Libya and Kuwait). For simplicity, I will refer to these results collectively as ‘2013’ throughout this column.

Similarly, while most interviews for Wave VII were conducted in 2022, some took place in 2021 (partially in Iraq and Lebanon, and entirely in Palestine and Tunisia). Therefore, I will refer to these results as ‘2022’ for the remainder of this piece.

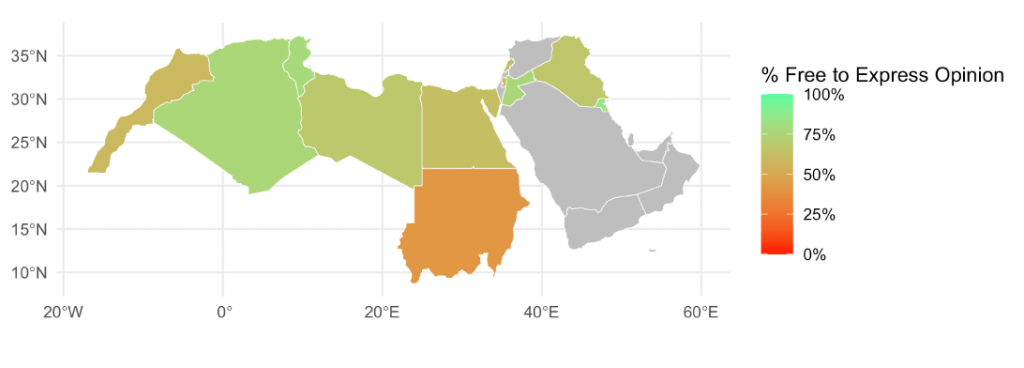

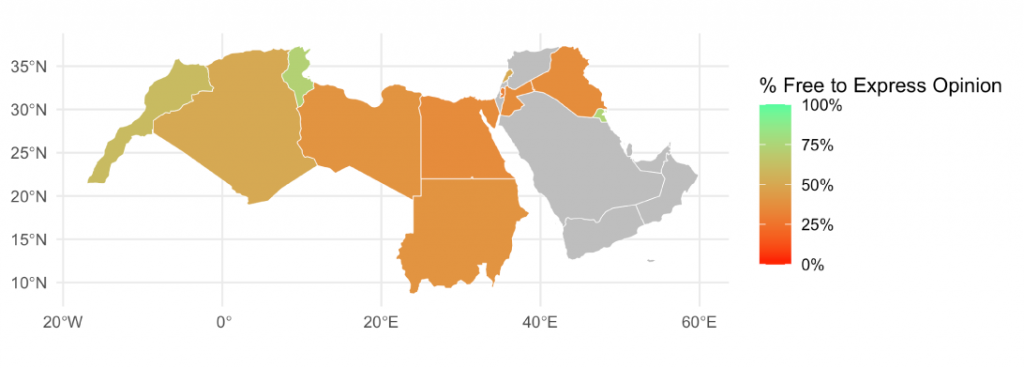

Figures 1 and 2 provide a visual representation of the estimated percentage of people who felt their freedom to express opinions is Guaranteed to a medium extent or Guaranteed to a great extent in 2013 and 2022 across 11 Arab countries. On these maps, each country’s colour signifies this percentage of people feeling free to express opinions, ranging from vibrant green (100%) to stark red (0%).

A striking pattern quickly becomes evident: in most countries, the sense of freedom to express opinions has diminished over the years, with the colours shifting noticeably from green to red. This decline is worrying from a human development perspective, as the freedom to voice one’s opinions is a key contributor to individual wellbeing and social progress.

Analyzing the data

The maps in Figures 1 and 2 were created by simplifying an ordinal variable that measures freedom of expression. The Arab Barometer survey asks respondents to assess the level of freedom to express opinions in their country, offering four categories: Not guaranteed, Guaranteed to a limited extent, Guaranteed to a medium extent, Guaranteed to a great extent.

For the analysis, I chose Guaranteed to a medium extent as the threshold and calculated the percentage of people who reported being above this level of freedom. But this approach might overlook the full richness of the ordinal information provided by the different categories. While some might suggest calculating the mean value, this method can be problematic as it involves assigning an arbitrary numerical scale to these ordinal categories.

In a previous column on happiness, I explored a similar issue regarding numerical scales and ordinal variables (Makdissi, 2024). Let’s adapt that discussion to the context of freedom to express opinions.

Imagine we have the following distribution among ten individuals: Not guaranteed, Guaranteed to a limited extent, Guaranteed to a limited extent, Guaranteed to a medium extent, Guaranteed to a medium extent, Guaranteed to a medium extent, Guaranteed to a great extent, Guaranteed to a great extent, Guaranteed to a great extent, Guaranteed to a great extent. Now, consider two possible numerical scales: Scale 1 (1, 2, 3, 4) and Scale 2 (1, 12, 13, 14). Both scales represent the same ordinal information.

But if we calculate the average using Scale 1, we get 3, suggesting an average freedom level of Guaranteed to a medium extent. Using Scale 2, the average becomes 12, which corresponds to Guaranteed to a limited extent. The numerical value changes because the scales differ, but more importantly, the assigned category also changes, highlighting the complexity and potential pitfalls of estimating the average value of an ordinal variable using an arbitrary numerical scale.

Allison and Foster (2004) argue that if one is interested in ranking countries according to their average level of an ordinal variable, such as freedom to express opinions, one should check for first-order stochastic dominance on the distribution of this variable to identify rankings that remain valid across all increasing numerical scales. Only when one country first-order dominates another can we assert that its average level of freedom to express opinions is higher for any increasing numerical scale applied to the ordinal variable.

In this analysis, I don’t consider missing values as random. Refusing to answer this specific question about freedom to express opinions is assumed to be associated with the respondent’s perception of her freedom. For this reason, I treat missing values as an ordinal category positioned below Not guaranteed on the freedom scale, interpreting it as a sign that the respondent’s freedom is so restricted that she chose not to answer the question.

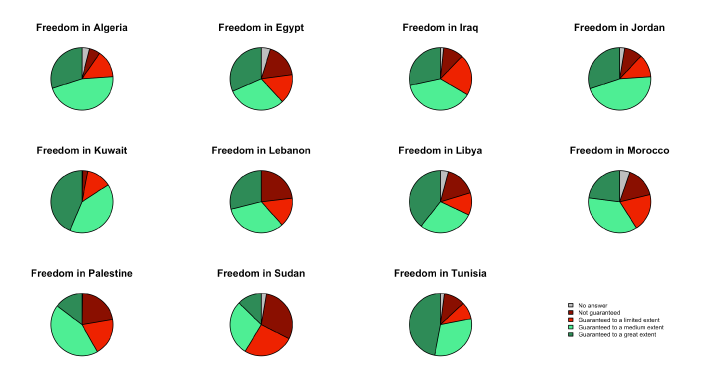

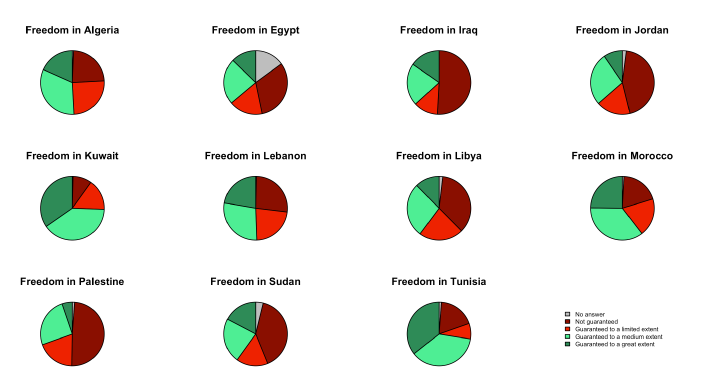

As explained in my previous column on happiness, a visual representation of the first-order dominance condition for an ordinal variable can be illustrated by comparing pie charts. In the case of freedom to express opinion, these pie charts could be constructed based on four categories of perceived freedom, along with the additional No answer category. To ensure consistency, the pie charts would start from a fixed point at 12 o’clock position.

I compare pairs of distributions, which could represent either two different years or two different countries. For one distribution to exhibit first-order stochastic dominance over the other:

- The pie chart segment representing the No answer category should be smaller in the dominating distribution.

- When combining the No answer and Not guaranteed segments, this combined segment should be smaller in the dominating distribution’s pie chart.

- Adding the Guaranteed to a limited extent segment to the previous categories, the combined segment should still be smaller for the dominating distribution.

- Adding the Guaranteed to a medium extent segment to the previous categories, the combined segment should still be smaller for the dominating distribution.

Thus, at each cumulative step (as we add one level of freedom to the others), the proportion of people at or below that level of freedom, including those who refused to answer, should be smaller for the country that first-order dominates the other.

Ranking Arab countries on freedom to express opinions

Figures 3 and 4 present the pie charts illustrating the average freedom to express opinions in 11 Arab countries for which data are available for both 2013 and 2022. While a clear pattern of declining freedom emerged in Figure 1 and 2, with the colours shifting from green to red, signalling a widespread erosion of freedom to express opinions, the more detailed comparison of distributions between these two years reveals a more complex trajectory.

In six countries – Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Sudan and Tunisia – it is impossible to rank the two years definitively. This suggests that for each of these countries, at least one numerical scale would indicate greater average freedom in 2013, while another could show higher average freedom in 2022.

But in four countries – Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon and Palestine – the average freedom to express opinions was unequivocally higher in 2013 than in 2022, consistently across all possible scales. In contrast, Morocco is the only country where average freedom improved, with levels in 2022 higher than in 2013.

These nuanced trends highlight that while the dichotomised view in Figures 1 and 2 suggests a significant decline in freedom to express opinions, a closer look reveals a more varied and complex pattern, with some countries experiencing mixed or even positive changes in the average freedom to express opinions.

In 2013, Kuwait emerges as a leader in freedom to express opinions. The average freedom to express opinions in Kuwait is unequivocally higher than in Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco and Sudan. Three other countries – Lebanon, Palestine and Tunisia – are not dominated by any other countries regarding average freedom to express opinions. Lebanon, Palestine and Tunisia all have unequivocally higher average freedom to express opinions than Sudan. Tunisia also has unequivocally higher average freedom to express opinions than Egypt, Libya and Morocco.

At the other end of the spectrum, Egypt, Morocco and Sudan do not dominate any other country. Egypt has unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Algeria, Kuwait, Libya and Tunisia. Sudan has unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon and Tunisia. Morocco has unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait and Tunisia.

The remaining countries fall between these extremes. Algeria has unequivocally higher average freedom to express opinions than Egypt, Libya and Morocco, and unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Kuwait. Both Iraq and Jordan have unequivocally higher average freedom to express opinions than Morocco and Sudan, and unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Kuwait. Libya has unequivocally higher average freedom to express opinions than Morocco, and unequivocally lower average freedom to express opinions than Tunisia

In 2022, Kuwait continues to stand out as a leader in terms of freedom to express opinions, with unequivocally higher averages compared to Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Palestine and Sudan, though it shows no dominance over Iraq, Lebanon or Tunisia.

Algeria also ranks highly, with higher averages than Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Palestine and Sudan, while showing no clear dominance over Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia.

Egypt remains on the lower end, with unequivocally lower averages than Algeria, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia, and no dominance over Iraq, Jordan, Libya or Palestine.

Similarly, Jordan ranks lower than Algeria, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia, with no clear dominance over Palestine or Sudan.

Lebanon, on the other hand, ranks higher than Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Palestine and Sudan, but shows no dominance over Morocco or Tunisia.

Tunisia is ranked higher than Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Palestine and Sudan, though it does not dominate Kuwait or Lebanon.

Libya remains among the lower-ranked countries, with unequivocally lower averages than Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia, and no dominance over Egypt, Iraq, Palestine or Sudan.

Morocco ranks higher than Egypt, Jordan, Palestine and Sudan, but does not dominate Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon or Tunisia. It is dominated only by Kuwait.

Palestine dominates no country, while Algeria, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia dominate it.

Sudan, similarly, only dominates Egypt, and is dominated by Algeria, Kuwait, Lebanon and Morocco.

Tunisia dominates Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Palestine and Sudan, and is not dominated by any other country.

The 2022 comparison reveals some similarities with 2013 but also notable changes. Kuwait continues to lead, reaffirming its dominance over several countries and maintaining its top position in terms of freedom to express opinions. Algeria, while still ranking highly, now has more non-dominance relationships with countries such as Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia, suggesting a narrowing of the differences between them.

Egypt remains on the lower end, consistently dominated by countries like Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia, with little change in its position since 2013. Jordan also shows minimal improvement, as it continues to be dominated by several countries. But its non-dominance relationships with Palestine and Sudan have remained stable.

Lebanon continues to rank highly, though it now has more non-dominance relationships in 2022 than in 2013, particularly with Morocco and Tunisia. Tunisia maintains a strong position, consistently outperforming Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Palestine and Sudan. Yet, its non-dominance relationships with Lebanon and Kuwait reflect an increased parity among the higher-ranking countries.

Libya and Sudan remain near the lower end of the spectrum, with Libya dominated by countries like Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia. Morocco, however, has strengthened its position, unequivocally dominating Palestine and Sudan. The relationship between Palestine and Sudan remains unchanged, with neither dominating the other, and both ranking below Tunisia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the analysis of freedom to express opinions in Arab countries over the past decade highlights both persistent challenges and some areas of improvement. While countries like Kuwait and Tunisia maintain their relatively high rankings, others, such as Egypt and Sudan, continue to face significant limitations. The nuanced shifts in freedom observed between 2013 and 2022 suggest that both government policies and social dynamics play a crucial role in shaping individual freedoms.

As these countries navigate their respective political and social landscapes, policy-makers must focus not only on removing legal restrictions but also on fostering environments where diverse opinions can be expressed without fear of reprisal or self-censorship. Moving forward, a deeper understanding of how freedom intersects with other dimensions of wellbeing will be essential for designing more comprehensive development strategies that prioritise human agency and social progress.

Further reading

Allison, RA, and JE Foster (2004) ‘Measuring health inequality using qualitative data’, Journal of Health Economics 23: 505-24.

Cohen, GA (2009) Why Not Socialism?, Princeton University Press.

Makdissi, P (2024) ‘Happiness in the Arab world: should we be concerned?’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

Nozick, R (1974), Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Basic Books.

Rawls, J (1971) A Theory of Justice, Belknap, Harvard University Press.

Sen, AK (1999) Development as Freedom, Alfred A Knopf/Oxford University Press.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.