In a nutshell

A number of regional trade agreements have included services as an integral aspect, among which has been the Arab free trade area in services (AFTAS) which was inaugurated in 2002, concluded in 2017, and entered into force in 2019 after its ratification by three member countries.

The seeds for services trade driving regional trade integration are there, but watering is needed to make them grow; that means executing the agreement, which requires a strong collective political nudge, as well as raising the level of awareness among different stakeholders.

Deep integration is essential: the framework for liberalisation of trade in services requires tackling regulatory measures in a more prudent way, handling markets with imperfect competition, and regionalisation of some regulatory bodies.

The prospects for trade integration among Arab countries have been dim for a long time. Merchandise trade as an engine of integration among Arab countries has suffered from severe limitations. The reasons vary from similar economic and trade structures, through the dominance of oil trade to the prevalence of non-tariff barriers (NTBs).

The end result has been modest intra-regional trade among Arab countries with estimates that range from 12% of total trade, including oil, to a maximum of 18% of total trade, excluding oil (see, for example, Atrash and Yousef, 2000, Zarrouk, 2000, Ghoneim and Péridy, 2013, and Arab Monetary Fund, 2023).

Can services play the role of engine of growth in trade?

Services trade has gained a great deal of attention since the inauguration of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. Indeed, ‘servicification’ – the process in which manufacturing relies increasingly on services as an integral element of the production process – is becoming an important phenomenon that is dominating global value chains (GVCs).

The services sector accounted for 67% of global GDP in 2021, compared with 53% in 1970 – and services trade accounted for 50% of global trade in terms of value added compared with 34% for industry and 16% for agriculture (World Bank and WTO, 2023).

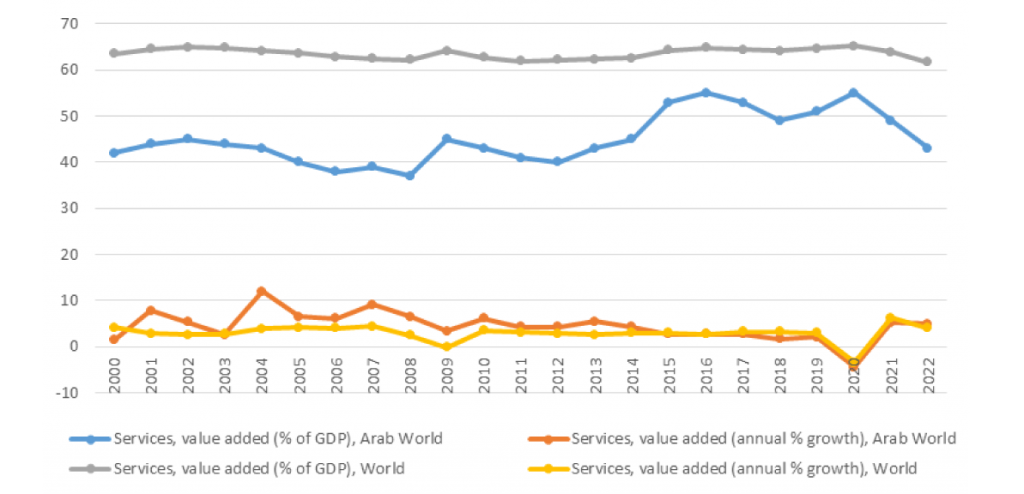

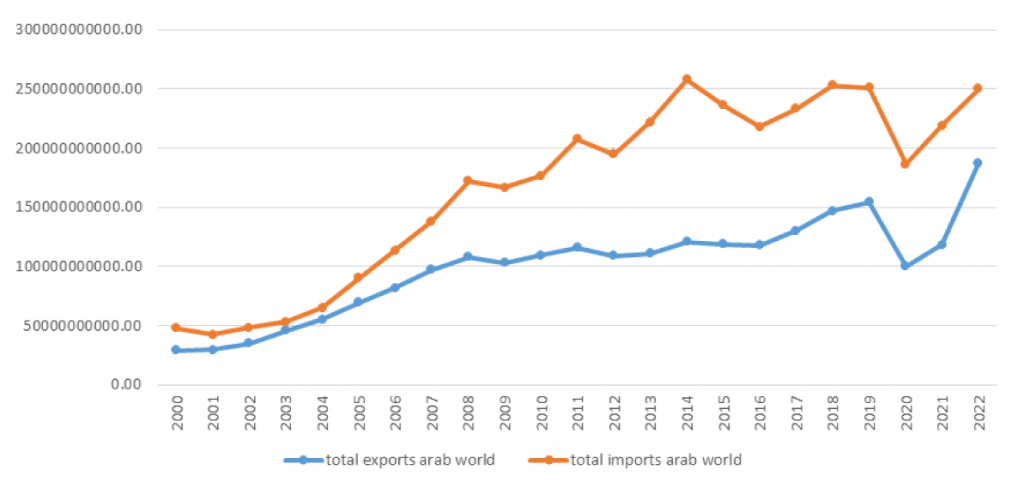

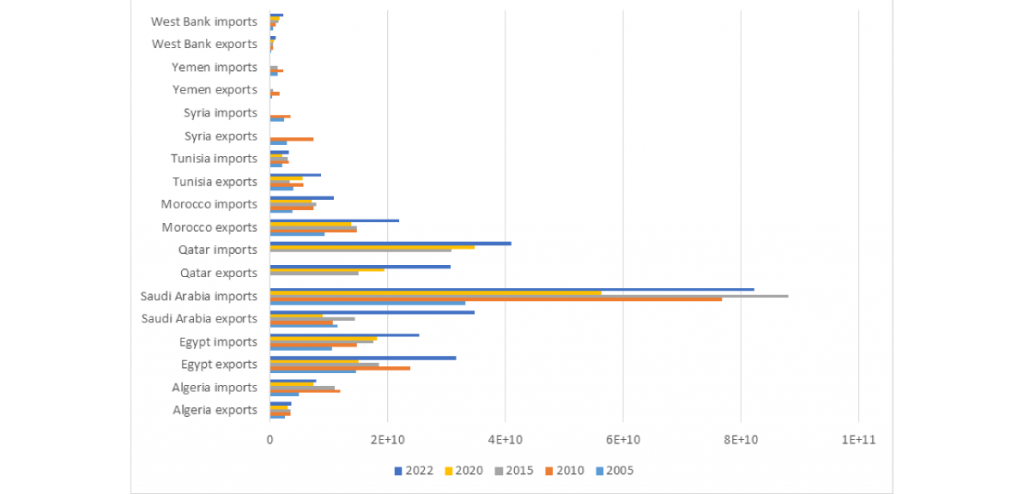

For Arab countries, services represent a varying share of GDP, ranging from 33% for Mauritania to 70% for Lebanon – see Figure 1. But services do not represent a high share of Arab exports and imports on regional, sub-regional and individual cases despite growing at fast rates – see Figures 2 and 3 (UNESCWA, 2019)

Moreover, the calculus of trade in services is rather different from trade in goods where liberalisation does not entail the traditional losses (for example, employment and balance of payments effects) associated with liberalisation of merchandise trade. For the main differences between trade in merchandise goods and trade in services see, for example, Copeland and Mattoo (2008).

A number of regional trade agreements have included services as an integral aspect, among which has been the Arab free trade area in services (AFTAS) which was inaugurated in 2002, concluded in 2017, and entered into force in 2019 after its ratification by three member countries.

Figure 1: Services value added as percentage of GDP and annual growth rates in the world and Arab countries

Despite the fact that the impact of such agreement has not yet materialised, the expectations that it can be a main engine of growth for regional integration are high. Several reasons explain such expectations:

- First, the increasing role of services in the GDP of Arab countries and the potential role of exports and imports of services as percentage of GDP (2.6% for Arab countries compared with 6% for ASEAN – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations), and the comparative advantage developed by a number of countries in a wide range of services (UNESCWA, 2018).

- Second, there is the de facto flourishing of trade in services among Arab countries in the tourism, transport, business and professional services, health, audiovisual, communications, financial and construction sectors.

- Third, the increasing membership of Arab countries in the AFTAS.

But such expectations are limited by the prevalence of NTBs to trade in services that render it to be relatively highly restricted in the Arab world (UNESCWA, 2018). Although preferential trade agreements (PTAs) are expected to lead only to marginal liberalisation, regional liberalisation of services should play a crucial role in GVC participation through backward and forward linkages, which is needed in the case of Arab countries.

Figure 2: Services imports and exports in Arab countries (current USD)

Figure 3: Services exports and imports in selected Arab countries

Steps undertaken

Among Arab countries, the 18 members of the Pan Arab Free Trade Area (PAFTA) set the framework of the AFTAS in 2002 and started negotiations in 2003. These continued until 2017, when the Beirut round was concluded. As a result, ten Arab countries provided detailed schedules: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemen. Afterwards, three other Arab countries joined: Bahrain, Kuwait and Palestine.

The number of sectors included in the committed schedules range from six sectors per country, as with Egypt, to 11 sectors per country, as with Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. Currently, six countries have finished signing and ratifying the AFTAS: Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and the UAE. Hence, the agreement has de jure entered into force. But no practical steps have been undertaken by the members to make it effective. In fact, and despite seven years having passed, AFTAS remains idle.

Several reasons explain the modest progress of the agreement:

- The lack of awareness among the different stakeholders on trade in services in general and AFTAS in specific.

- The blurred political scene in the Arab region in general and in some members in particular, such as Palestine and Sudan.

- The lost enthusiasm for enhancing trade in general and its role of an engine of growth.

- The scarcity and, in some cases, the absence of data on trade in services whether in terms of flows by the four different modes of trade in services, or in terms of NTBs affecting trade in services.

What needs to be done?

The seeds for services trade playing a pivotal role as an engine for regional trade integration and enhancing GVCs are there, but watering is needed to make them grow. The seeds are the AFTAS and the de facto high stage of trade in services integration among Arab countries (compared with merchandise trade integration). Moreover, there are several sectors where the GATS commitments of the AFTAS members overlap, as in communications, financial services and tourism, which hints at similar interests in liberalisation. (ECES, 2009)

Yet watering is still needed. This should consist of moving from an ink on paper agreement to executing the agreement, which requires a strong collective political nudge, as well as raising the level of awareness among different stakeholders. The rules of the game in services trade, on the exports and imports sides, need to be explained, as they are completely different from their counterparts in merchandise trade whether in terms of trade policy tools or in terms of their effects on employment and the balance of payments.

Hence, the framework for liberalisation of trade in services requires tackling regulatory measures in a more prudent way, handling markets with imperfect competition, and regionalisation of some regulatory bodies.

In other words, deep integration – which deals with issues behind the borders, including rules and regulations, as opposed to shallow integration, which only deals with border issues – is essential for the success of liberalisation of trade in services (Guillin et al, 2023). Arab governments, in collaboration with regional and international organisations should devote more effort to constructing databases on trade in services as well as the NTBs that affect such trade, to be able to enhance the impact of liberalising trade in services.

The most comprehensive database available is the Services Trade Restrictions (STR) Database published by the World Bank, which provides a broad yet incomplete coverage for Arab countries (only five service sectors) and data were collected in 2008.The OECD picked up on the STR and produced the Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), which has a wider coverage of sectors (22) and countries, yet does not as yet include any Arab countries.

Further reading

Al Atrash, H, and T Yousef (2000) ‘Intra-Arab Trade: Is It Too Little’, IMF Working Paper WP/00/01.

Arab Monetary Fund (2023) Unified Arab Economic Report.

Copeland, B, and A Mattoo (2008) ‘The Basic Economics of Services Trade’, in A Mattoo, R Stern and G Zanini (eds) A Handbook of International Trade in Services, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and Oxford University Press.

ECES, Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (2009) ‘Liberalisation of Trade in Services in Four Arab South Mediterranean Countries: An Unutilised Vehicle for Intra-regional Trade Integration’, European Institute of the Mediterranean Yearbook.

Ghoneim, AF, and N Péridy (2013) ‘Trade effects of Non-Tariff Measures (NTMs): Some new insights into MENA countries’, Journal of Economic Integration 28(4): 375-92.

Guillin, A, I Rabaud and C Zaki (2023) ‘Does the depth of trade agreements matter for trade in services?’

UNESCWA, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2018) Assessing Arab Economic Integration: Trade in Services as a Driver of Growth and Development.

UNESCWA, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2019), Assessing Arab Economic Integration: Trade in Services as a Driver of Growth and Development.

World Bank and WTO (2023) Trade in services for development: Fostering sustainable growth and economic diversification.

Zarrouk, J (2000) ’Para-Tariff Measures in Arab Countries’, in H Kheir-El-Din and B Hoekman (eds) Trade Policy Developments in the Middle East and North Africa, ERF.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.