In a nutshell

Several factors explain rising informality in Egypt, including a fall in the share of workers obtaining social insurance on entry to jobs, an ‘informality trap’ with limited transitions into social insurance once employed, and greater losses of social insurance among the employed.

Reforms will be needed to make social insurance more appealing to workers and firms, including less expensive and more flexible contributions, better benefits, higher quality of administration, and shifting to a progressive system.

Egypt’s social insurance system could be reformed in a way that involves funding by consumption taxes instead of the current contributory system; decoupling social insurance benefits from employment could increase labour mobility and entrepreneurship.

Over half of the world’s workers (58%) lack social insurance coverage and are thus informal (International Labour Organisation, 2023). Informality has been a particular challenge for the Middle East and North Africa, where the inability of countries to provide good (formal) jobs has been a continuing struggle (Gatti et al, 2014).

Egypt is a notable example: the country has been unable to expand social insurance coverage, instead experiencing declines in coverage. Contributory social insurance coverage declined from 52% of workers in 1998 to 32% by 2018 (Barsoum and Selwaness, 2022). Recent changes in the structure of the economy and employment do not seem to be responsible for these continuing declines (Assaad and Wahby, 2023).

So, why does social insurance coverage continue to decline? This column explores the dynamics of social insurance in Egypt over the period 1998-2018, providing new insight into declines in coverage (see Krafft and Hannafi, 2023, for further details).

Dynamics of social insurance coverage

Analysing social insurance dynamics requires panel microdata on workers and their contributory social insurance coverage. We therefore use the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) waves of 1998, 2006, 2012 and 2018 (Krafft et al, 2021; OAMDI, 2019). We can assess dynamics from 1998-2006, 2006-12 and 2012-18.

The panel nature of the data allows us to assess dynamics directly, comparing the same individuals at two points in time. We use two key margins of social insurance dynamics: gaining social insurance (often distinguishing at entry into a job from while remaining in employment) and losing social insurance (distinguishing between while remaining in employment and when exiting work).

In Krafft and Hannafi (2023), we present detailed descriptive and multivariate results for social insurance dynamics. We summarise the results here.

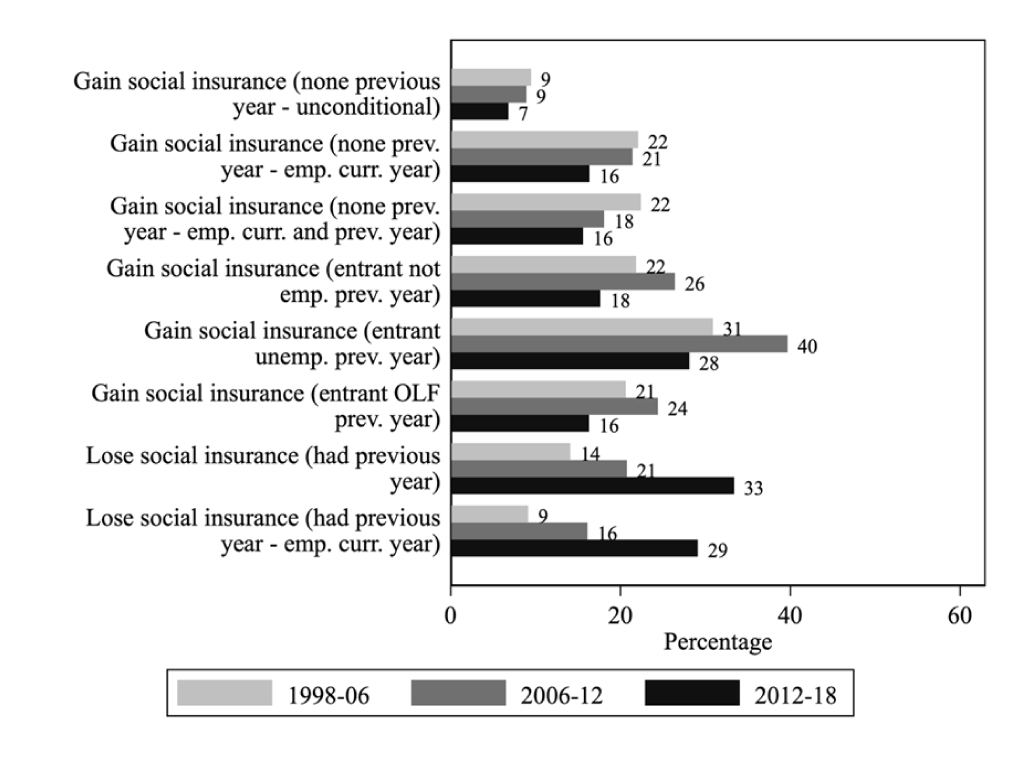

Figure 1 shows the panel transitions of gaining and losing social insurance coverage over 1998-2006, 2006-12 and 2012-18. The share of those without social insurance gaining social insurance declined from 2006-12 (9%) to 2012-18 (7%). Focusing on those who were employed in the latter period, 21% of those without social insurance in 2006 who were then employed in 2012 gained social insurance, compared with 16% of those over the period from 2012 to 2018. Fewer workers were gaining social insurance over time.

Our analysis further distinguishes between those employed in both periods and ‘entrants’, who were not employed in the first period but became so in the later period. The share gaining social insurance while employed fell over time: from 22% in 1998-2006 to 18% in 2006-12 and 16% in 2012-18.

Entrants (those who were not employed initially and subsequently obtained employment) experienced an increase in gaining social insurance from 1998-2006 (22%) to 2006-12 (26%), but then a further drop in 2012-18 (18%). This pattern over time held for both entrants from unemployment and entrants from being out of the labour force. Those entering from unemployment (who were likely to have had higher reservation working conditions) were more likely to gain social insurance at entry.

A troubling trend is that losing social insurance increased substantially over time. Between 1998 and 2006, 14% of those with social insurance lost it, compared with 21% in 2006-12 and 33% over 2012-18. These results are not driven by additional exits from the labour force. Among those who remained employed from 1998 to 2006, only 9% lost social insurance, compared with 16% in 2006-12 and 29% over 2012-18.

Figure 1: Panel transition rates (percentage), individuals aged 18-59 in 2006/2012/2018 over panels 1998-2006, 2006-12 and 2012-18

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the ELMPS 2018 retrospective data.

Notes: Entrant is an individual who was not employed in the previous year and is employed in the current year.

The analysis highlights key predictors of gaining and losing social insurance coverage. Workers who were in the public sector, in large firms, and in fixed establishments were more likely to obtain social insurance coverage. Workers who were in professional or operations occupations, who were more educated and older, or who had more years in their current job were more likely to gain social insurance. These groups were also often, but not always, less likely to lose social insurance.

Reforming and expanding social insurance

Contributory social insurance is critically important for ensuring that workers can retire and have old-age income. Enrolling in social insurance, and thus formalising employment, is associated not only with benefits in old age, but also a number of benefits and protections while working (Barsoum and Selwaness, 2022).

Yet social insurance coverage has been declining in Egypt. As this research demonstrates, fewer workers – both entrants and those already employed – are gaining social insurance coverage. Increasing numbers of workers are losing social insurance, even when they remain employed. How can social insurance coverage be increased in Egypt?

Egypt has already made a number of reforms to encourage firms to formalise (register), a pre-requisite to social insurance coverage for their workers, and to improve the social insurance system (Barsoum and Selwaness, 2022; Shehata & Partners Law Firm, 2020). Although social insurance coverage rates had not increased substantially as of 2021 (Assaad and Wahby, 2023), it may take some time for the effects of the reforms to be apparent. Future research will also need to explore the long-term impacts of these reforms.

A variety of approaches have been undertaken to try to increase take-up of social insurance in other low- and middle-income countries, including premium subsidies, additional/bundled benefits, information campaigns and enrolment assistance (Canelas and Niño-Zarazúa, 2022a). Workers are more willing to pay for less expensive and more flexible contributions, better benefits and higher quality administration (Miti et al, 2021), suggesting key directions for reform that could also increase take-up.

Challenges with the design of the social insurance system may require further reforms. For example, despite reforms, social insurance in Egypt remains regressive (Barsoum and Selwaness, 2022). Transforming it into a progressive system could be important for increasing the appeal of enrolling in social insurance to workers. Ensuring that firms are formal may require different efforts, for example, simplified tax procedures and lower tax rates for micro firms in Brazil increased firm formality and employment (Fajnzylber et al, 2011).

One possible, more radical reform to the social insurance system is moving financing from payroll to consumption taxes (Anton-Sarabia et al, 2012; Esteban-Pretel and Kitao, 2021; Pagés, 2017). This reform would essentially move from a contributory to non-contributory scheme.

While this would certainly expand the number of people who could access benefits in old age, a downside is that it might also make workers more willing to work for unregistered firms or in positions that lack other benefits. The global evidence on these effects is mixed (Canelas and Niño-Zarazúa, 2022a, 2022b).

But an upside would be that decoupling social insurance benefits from employment could increase labour mobility and entrepreneurship, since transitions to non-wage work often led to the loss of social insurance.

Further reading

Anton-Sarabia, Arturo, Fausto Hernandez and Santiago Levy (2012) ‘The End of Informality in Mexico? Fiscal Reform for Universal Social Insurance’, Inter-American Development Bank.

Assaad, Ragui, and Sarah Wahby (2023) ‘Why Is Social Insurance Coverage Falling in Egypt? A Decomposition Analysis’, ERF Working Paper No. 1658.

Barsoum, Ghada, and Irene Selwaness (2022) ‘Egypt’s Reformed Social Insurance System: How Might Design Change Incentivize Enrolment?’, International Social Security Review 75(2): 47-74.

Canelas, Carla, and Miguel Niño-Zarazúa (2022a) ‘Social Protection and the Informal Economy: What Do We Know?’, ESCAP, Social Development Division.

Canelas, Carla, and Miguel Niño-Zarazúa (2022b) ‘Informality and Pension Reforms in Bolivia: The Case of Renta Dignidad’, Journal of Development Studies 58(7): 1436-58.

Esteban-Pretel, Julen, and Sagiri Kitao (2021) ‘Labor Market Policies in a Dual Economy’, Labour Economics 68: 101956.

Fajnzylber, Pablo, William Maloney and Gabriel Montes-Rojas (2011) ‘Does Formality Improve Micro-Firm Performance? Evidence from the Brazilian SIMPLES Program’, Journal of Development Economics 94(2): 262-76.

Gatti, Roberta, Diego Angel-Urdinola, Joana Silva and Andras Bodor (2014) Striving for Better Jobs: The Challenge of Informality in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

International Labour Organization (2023) ‘World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023’.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Khandker Wahedur Rahman (2021) ‘Introducing the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey 2018’, IZA Journal of Development and Migration 12(12): 1-40.

Krafft, Caroline, and Cyrine Hannafi (2023) ‘The Dynamics of Social Insurance in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper Series No. 1655.

Miti, Jairous Joseph, Mikko Perkio, Anna Metteri and Salla Atkins (2021) ‘Factors Associated with Willingness to Pay for Health Insurance and Pension Scheme among Informal Economy Workers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review’, International Journal of Social Economics 48(1): 17-37.

OAMDI (2019) ‘Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS). Version 2.0 of Licensed Data Files; ELMPS 2018’,

Pagés, Carmen (2017) ‘Do Payroll Tax Cuts Boost Formal Jobs in Developing Countries?’, IZA World of Labor.

Shehata & Partners Law Firm (2020) ‘Overview of the New SMEs Law’.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Ford Foundation grant to ERF for the project ‘Renewing the Social Contract: Working Toward a More Inclusive Social Insurance System in Egypt’. The authors appreciate the comments of participants in the ‘Workshop on social insurance in Egypt,’ particularly discussant Rania Roushdy.