In a nutshell

Digitalization is one of the main factors shaping the global economy, but a third of the population in the Arab world—about 142 million people—is not yet connected. Digital development in the Arab world has failed up to now to have the transformative impact it has had in other developing regions, where improvements in business climate and connectivity have unleashed economic activity; created new jobs; and supported, better public services.

To unleash the power of digitalization and avoid falling farther behind, Arab countries need to reform their education systems, build trust in digitalization through improved cybersecurity, support the private sector, and work with international partners.

New digital technologies are bringing about massive shifts in global output, trade, and employment. The Internet has connected people in virtually every corner of the planet, with 63 percent of the world connect in 2021 . Still, more than 2.9 billion people are not connected, 96% of them living in developing countries.

Digitalization has benefited billions of people—but not everyone has benefited equally

The digital divide between advanced and developing economies, as well as within many countries, is wide. And the stronger the network, the worse not being connected to it is. People left behind face daunting barriers to acquiring knowledge, building wealth, and improving their well-being.

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the digital transformation in both public and private sector activities. Countries adapted to the shock at different paces, widening the digital divide in many places, including the Arab world. Lockdown brought many new people online and forced the region to modernize at breakneck speed. But the groups already facing marginalization benefited least.

Digitalization brings the promise of intellectual and economic liberation—but it also risks entrenching old inequalities and creating new ones by widening digital divides across income groups and by gender and disrupting labor markets.

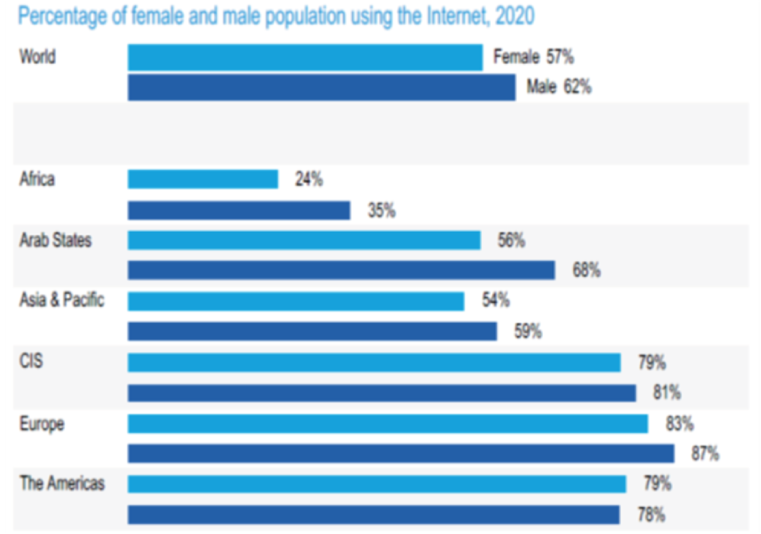

In 2020, about 62 percent of the world’s male population and about 57 percent of the female population used the Internet, a female to male ratio of 0.92 (figure 1). Despite some progress in narrowing the gender gap in Internet use in recent years, some 234 million fewer women than men used the Internet in 2020. In the Arab region, where about 142 million were unconnected in 2021, 56 percent of women and 68 percent of men were online, leaving a gender gap of 0.82.

Figure 1: Share of world’s population using the Internet, by gender, 2020

Source: International Telecommunications Union, 2021. Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2020 (Geneva), https://www.itu.i nt/en/ ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2021.pdf.

Digitalization policies in the Arab countries do not appear to be having the desired result

Nearly all Arab countries investigated as part of a recent report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and ERF had developed national strategies for digitalization. But the impacts of these plans have been limited, suggesting that the policies are not working as intended.

Indeed, digitalization in the Arab world is a story of squandered opportunities. Digital development has failed to have the transformative impact it has had in many other emerging economies, where improvements in the business climate and digital connectivity have unleashed economic activity, created new jobs, and improved public services. Many Arab countries lag behind other countries in both the digitalization of public services and the use of new technology by businesses and financial institutions. As a result, the public sector remains slow and inefficient and the private sector uncompetitive.

To remedy the situation, Arab countries need to move quickly

At the state level, countries need to move beyond “e-government” to develop full-fledged digital government services. Doing so will require engineering a user-driven public administration in which services are designed to maximize efficiency and quality for all citizens, not just retro-fitting new technology into clunky old systems.

Tackling this problem is critical. In other regions, digitalization of public services has played a leading role in the technological transformation of the wider economy. Opportunities in the Arab world have been missed. Policy-makers urgently need to make up for lost time.

Failing to digitalize means falling farther and farther behind

Increased digital connectivity can raise productivity, increase growth, and reduce inequality, transforming people’s lives. Increases in Internet access and use, as well as increased participation in global value chains within services trade, leads to significant increases in economic activity and well-being. Failing to digitalize while other countries plow ahead will cause countries and regions to fall farther behind.

For digitalization to work, it needs to be all-encompassing

All-encompassing digital transformation will have significant and unpredictable impacts on a range of factors, including inequality, employment, trade, investment, supply chains, migration, service delivery, and even environmental and climate-related challenges. To manage this complexity, it is critical that Arab countries address the implications of such transformations early on, through appropriate policy interventions, and invest in human capital to help realize and strengthen the economic and social benefits of new technologies. Such investment would help curb some of the risks associated with widening digital divides and increased inequality.

Policy-makers should also be mindful of wider national strategies and how digitalization fits into these targets. Governments in the region should ensure that development of the digital economy aligns with their commitments to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and leave no one behind, for example, particularly in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The pandemic increased the importance of inclusive economic development

The pandemic exacted a massive human toll and caused unprecedented reversals in poverty reduction, increasing the number of people living in extreme poverty by 97 million in 2021 and exacerbating income inequality, both between and within countries. The health and economic impacts of the pandemic increased imbalances that existed before 2020 in both developed and developing economies.

Large divides in digital literacy, infrastructure, and affordability led to highly unequal economic opportunities and outcomes duringthe pandemic. Digital technologies, which played a critical role in sustaining economic activity during lockdowns, magnified the inequalities caused by the crisis, as hundreds of millions of educated people with digital technology were able to work from home while billions of others could not.

Five sets of actions are critical for policymakers in the region to consider:

- Reform education and training programs to meet the requirements of the digital age, including languages. Encourage the acquisition of skills that complement the new technologies by both young and older workers, paying special attention to women and other disadvantaged groups.

- Strengthen trust and confidence in digital technologies by improving cybersecurity and adopting and enforcing appropriate rules and regulations.

- Policy-makers should develop and enforce regulations to foster competitive markets, so that digitally savvy firms can compete with one another without being bulldozed by larger organizations whose monopoly power could stifle innovation across the region.

- Adjust taxation so that it does not penalize or create unfair advantages for certain operators; simplify procedures for creating and expanding businesses; increase access to finance; and foster competition.

- Engage with partners at the international level. Arab countries need to be more active in global efforts to design good regulatory practices and facilitate digital trade and e-commerce through cooperation with trading partners.

Knowledge gaps need to be filled

Understanding of both the upsides and downsides of digitalization on economic and social outcomes is very limited in the Arab world, according to the UNDP–ERF project. More needs to be learned about how and why firms and households adopt digital technologies; the extent to which they use such technologies; and the ways in which they affect productivity, jobs, and incomes.

At the firm level, research should identify how firms decide to adopt digital technologies and how their doing so affects productivity, wages, and incomes. The hypothesis of divergence between leading and lagging firms in the adoption of digital technologies should be tested in Arab countries. Evidence on the impact of digital technologies on growth, demand for skills, wages, and the distribution of income is almost nonexistent, and very little research has been done on how the large gender gap in digital access, use, and skills could be narrowed.

At the sectoral level, research could be undertaken to understand the extent to which digital technologies are changing the allocation of resources between old and new activities. The process of job destruction and creation needs to be assessed and explained. The contribution of digitalization to diversification and structural transformation in Arab countries remains a major concern and needs to be documented and assessed.

Work also needs to be done to understand the impact of digitalization at the macroeconomic level. Many research questions raised by this report need to be addressed, including the following:

- What is the impact of digitalization on aggregate productivity growth (labor productivity and total factor productivity)?

- How is digitalization affecting labor market dynamics, including the role of skills and labor matching?

- What are the likely implications of digitalization for competition and market structures in Arab countries?

- What is the impact on trade, and how is digitalization affecting competitiveness and the prospects of participation in global value chains?

- What is the impact of digitalization on inequality and poverty in Arab countries?

- What is the impact on women’s participation in the labor market?

- What role does the lack of language proficiency play in sustaining digital divides?

As the answers to these questions will depend on the policy ecosystems that accompany digitalization, empirical trials and model simulations are necessary to better design coherent sets of policies that accompany a more inclusive digital transformation than experienced to date.