In a nutshell

If the complementarity between humans and machines observed in previous spells of technical progress is threatened by continued automation, countries in Africa and the Middle East will need drastic increases in productivity gains in their informal sectors.

Three areas of investment are required: building human capital for a young labour force; increasing the productivity of informal workers and enterprises; and creating fiscal space for investments in human capital by strengthening underused tax instruments.

The next phase of the Africa Continental Free Trade Area presents an opportunity for African countries to establish common positions on e-commerce and the harmonisation of digital economy regulations.

Digitalisation is just starting. The speed at which this transformation takes place will depend on the performance of the services sector through two channels:

- ‘Servicification’ – more intensive use of services in manufacturing reflected in a growing share of services in GDP.

- ‘Servitisation’ – services like after-sales bundled with goods in the sales of firms.

For both the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), digitalisation presents an opportunity to raise productivity by speeding up structural transformation.

The success of digitalisation rests on the combination of hard inputs – information and communication technologies (ICT), that is, submarine cable broadband lines (SMCs) and Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) cum Colocation Data Centres (CDCs) – and soft inputs often called DIGITECH, that is, additive manufacturing like 3D printing, machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT).

We explore these aspects of digitalisation in MENA and SSA in a recent study (Melo and Solleder, 2022), which describes the challenges and progress to date in both regions.

For MENA, which has largely failed to achieve structural transformation via manufacturing-led growth, the digital transformation (where value creation shifts from capital to knowledge) presents an opportunity to achieve a service-sector-led high-productivity-growth structural transformation. This has proved elusive to date: for example, the average annual rate of labour productivity growth in services in the region over the period 1995-2000 was 0.5%, about half the rate of in the next slowest developing region (Nayyar et al, 2021).

For SSA countries, even though so far there is no evidence of negative employment effects of technology (Hjort and Poulsen, 2015; Choi et al, 2020), the arrival of digitalisation could rob the region of the demographic dividend opportunity offered by rising wages in China.

Low readiness for e-commerce in MENA and SSA

Cross-border flows of data (e-commerce) will be an important aspect of digitalisation. Drawing on a classification of national data infrastructure preparedness along a ladder for 45 MENA and SSA countries, we document some catching up in terms of connectivity to the internet for MENA. But relative to other regions, usage is low in both regions, especially in SSA. The usage/affordability landscape is also very heterogeneous across countries in both regions.

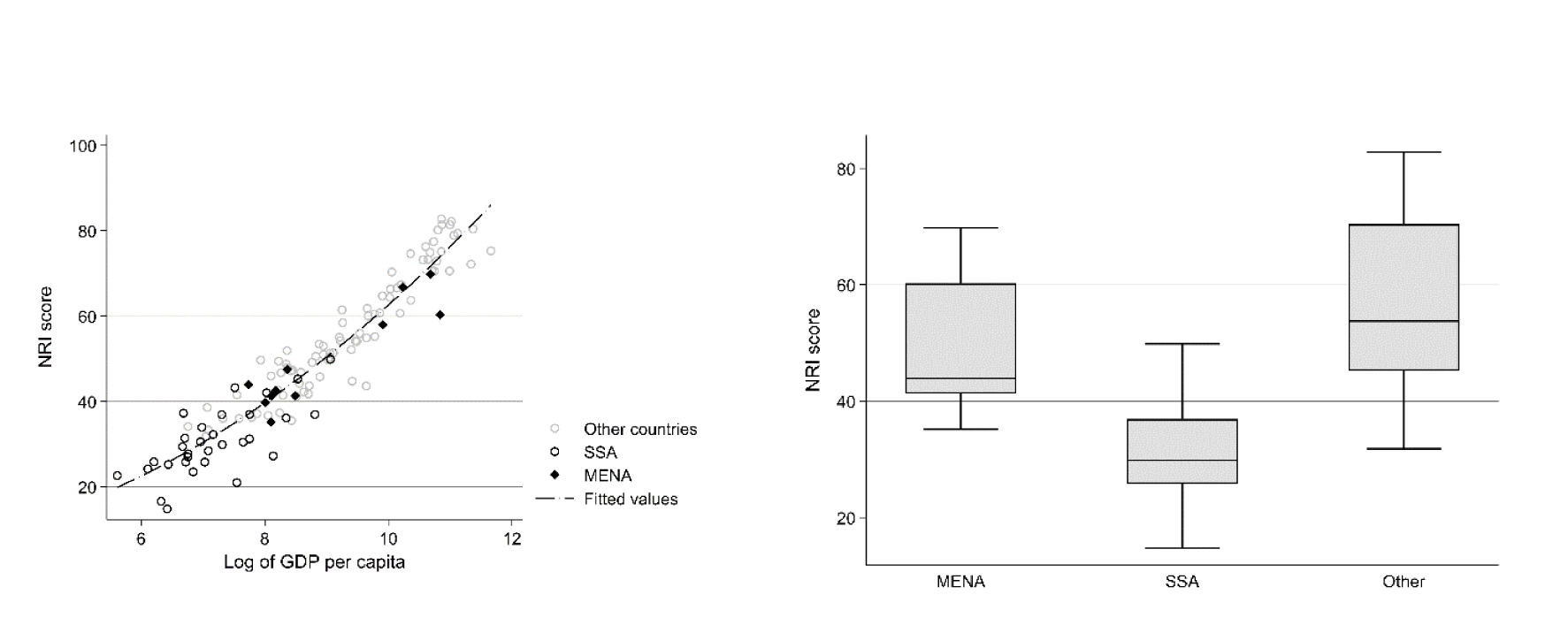

MENA countries that are not members of the Gulf Cooperation Council are doing relatively well on the hard side (SMCs, IXPs) with strong growth of mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions and mobile data consumption. But they are doing poorly on a network readiness index (NRI) because of low ICT skills and education outcomes (see Figure 1).

The World Bank (2021) attributes low NRI scores to a shortfall of connectivity that can be summarised in three types of gaps: coverage (access to the internet); usage (access but no use); and consumption (usage too low to support basic and economic functions). Good ICT infrastructure but low DIGITECH have combined to present a challenge towards successful digitalisation.

For most of SSA, low NRI scores are attributable to a lack of hard infrastructure (distance from transmission relays), high costs of connectivity (even for countries with access to hard infrastructure) and deficiencies in digital skills. These high costs are related to market size in networks, non-competitive markets for provider services and, in some cases, high rates of taxation for mobile operators. For SSA, we document that poor/unaffordable connectivity, lack of awareness and digital skills reflected in low NRI scores, have combined to create a ‘digital divide’ with other regions.

Figure 1: Network Readiness Index (NRI) scores in MENA and SSA

Notes: Data for 132 countries (31 SSA and 14 MENA). Scores based on a simple average of scores (number of indices per pillar in parenthesis) over four pillars: Technology (16), people (16), Governance (14), Impact (14). Except for technology, SSA and MENA, figure in the bottom of the regional rankings

Source: Melo and Solleder; figure 3 from data in Dutta and Lanvin (2021).

Across MENA, the share of services in GDP increased by 7.5 percentage points over the period from 1990 to 2018, half that in middle-income countries (MICs), reaching 49.7% of GDP relative to 54.7% in MICs. Weak exports of services reflect the prevalence of transport and tourism services with some countries registering a negative growth of ‘other commercial services’ over the period 2015-19 (Hoekman, 2021).

Low participation in supply chain trade

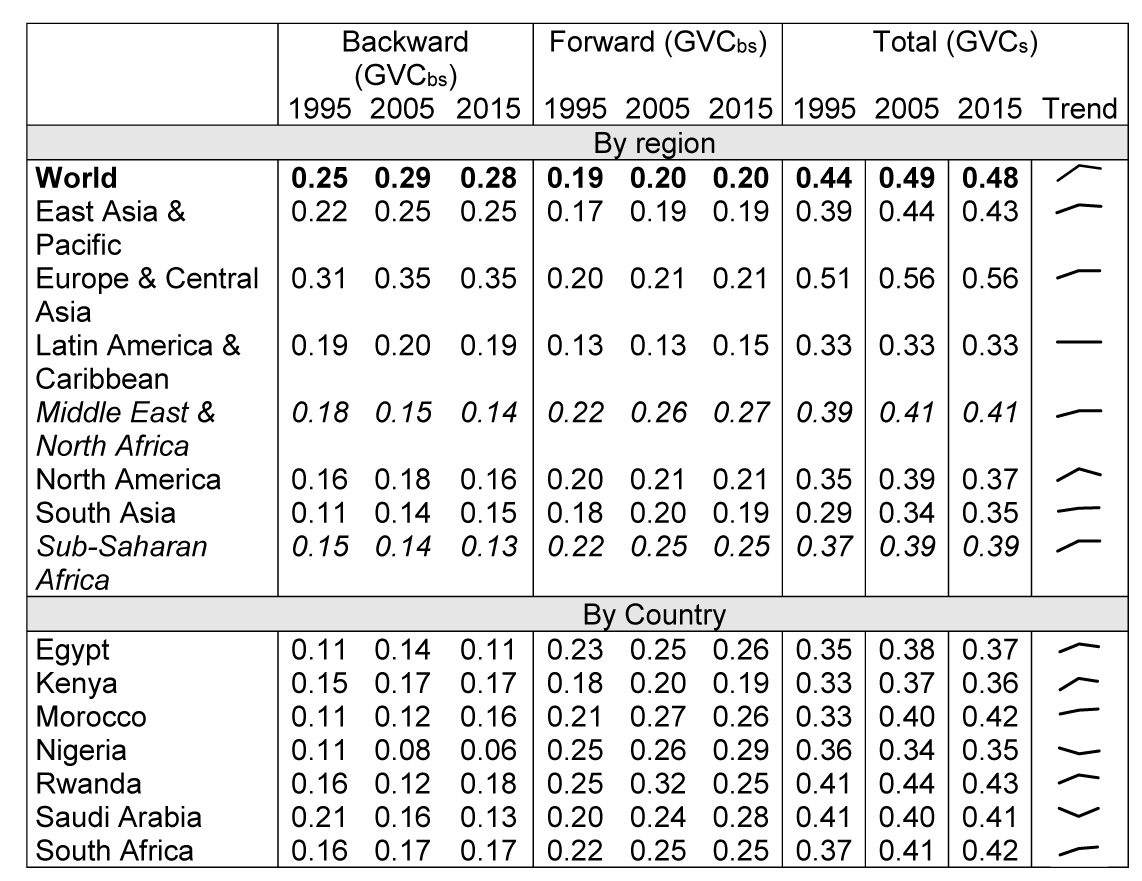

Both MENA and SSA have the lowest import content of exports across regions (low backward GVCbs values in Table 1). Exports from MENA and SSA embody fewer intermediate imports – a conduit for innovation and productivity improvements – than other regions.

This pattern is consistent with high policy-imposed trade barriers and of other barriers to trade like inhospitable geography, or at least with trade costs remaining stubbornly high, falling less rapidly than in other regions. Between 1995 and 2015, relative to those of the top 15 world leaders, bilateral trade costs of (MENA) [SSA] countries have only caught up by (35) [30] percentage points, standing in 2015 at (122%) [226%] above the leaders’ trade costs.

On the forward side (GVCfs), both regions have the highest shares throughout the period, an indication of exports concentrated in raw materials and agricultural products with little transformation. Forward participation rates for both regions are a third higher than elsewhere, an indication of further transformation – often high value-added – before final consumption.

The participation rates for a selection of countries in the bottom of Table 1 shows a low import content of exports in the resource-rich countries – Egypt, Morocco and Nigeria (low GVCbs values) – while exports undergo further processing in the importing countries (high GVCfs values). Morocco, Kenya and Rwanda stand out for increased upstream and downstream participation. For other regions, GVCfs measures have either remained constant or decreased. Value-added generated in the region has not gone up. These trends slow structural transformation.

Table 1: Trends in GVC participation by region

Notes. Simple average across countries within regions. (GVCbs) is the share of imports in gross exports and (GVCfs) is the share of gross exports that enters into exports of destination country. (GVCs) = (GVCbs)+(GVCfs)

Source: Melo and Solleder (2022, table 3).

Correlates of trade flows

Firms operating in environments with performing data ecosystems export more data-related services. Observing a strong positive correlation between the export of information services as a share of total services exports and CDCs per million population, Marel (2021) estimates that a 10% increase in CDCs results in a statistically significant expansion of data-related services of 1.6%.

In addition, access to platforms is associated with a decline in the export shares of the largest firms in bilateral trade, suggesting that access to platforms levels the playing field across firm size (Meng Sun, 2021).

Our study reports new estimates of the correlates of aggregate bilateral trade flows as captured by measures of GVC participation, trade costs (Arvis et al, 2016) and NRI. We estimate that an increase in telecoms subscriptions has a stable direct effect on GVC trade and an indirect effect through a decrease in trade costs. A 10% increase in telecoms subscriptions in MENA and SSA is associated with a 4% direct increase in GVC participation and a 2% indirect increase via lower trade costs.

Looking ahead

We conclude that ‘this time may be different’ if, as observed by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019), the labour displacement effects of automation are not compensated by substantial reinstatement effects observed during past episodes of widespread technological change when jobs were created to implement the new technologies.

If so, the complementarity between humans and machines observed in previous spells of technical progress may be threatened by the continued growth in automation and robots.

To counter or attenuate this possible outcome, at the national level, SSA (and to a lesser extent MENA) countries need a drastic increase in productivity gains in their large informal sectors, which account for close to 60% of employment (ILO, 2018).

Three areas of investment are required in addition to social protection:

- Building human capital for a young, rapidly growing, and largely low-skilled labour force.

- Increasing the productivity of informal workers and enterprises including through the creation of new formal low-skill jobs.

- Creating fiscal space for investments in human capital by strengthening underused tax instruments including through digitalisation to increase the efficiency of tax design and tax collection (Choi et al, 2020).

At the international level, African countries need to cooperate to avert ‘data colonialisms’ (Mayer, 2021). Several reports, notably UNCTAD (2021), have observed that digital disparities across countries may be increasing in a world increasingly data-driven. The next phase of the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents an opportunity for African countries to establish common positions on e-commerce and harmonisation of digital economy regulations.

Further reading

Acemoglu, D, and P Restrepo (2019) ‘Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2): 3-30

Arvis, JF, Y Duval and B Shepherd (2016) ‘Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1996-2015’, World Trade Review 15(3): 451-74.

Choi, J, M Dutz and Z Usman (eds) (2020) The Future of Work in Africa: Harnessing the Potential of Digital Technologies for All.

Dutta, S, and B Lanvin (eds) (2021) The Network Readiness Index 2020: Accelerating Digital Transformation in a Post-Covid Global Economy, Portulans Institute.

Hjort, J, and J Poulsen (2019) ‘The Arrival of the Fast Internet and Employment in Africa’, American Economic Review 109(3): 1032-79

Hoekman, B (2021) ‘Digitalization, International Trade and Arab Economies: External Policy Dimensions’, ERF Working Paper No. 1484.

ILO (International Labor Office) (2018) Women and Men in the Informal Sector: A Statistical Picture, 3rd edition.

Marel, E van der (2021) ‘Sources of Comparative Advantage in Data-Related Services’, Working Paper EUI RSCAS 30.

Mayer, J (2020) ‘Development Strategies for Middle-income Countries in a Digital World – Insights from Modern Trade Theory’, World Economy 44: 2515-46.

Melo, J de, and JM Solleder (2022) ‘Structural Transformation in MENA and SSA: The Role of Digitalization’, ERF Working Paper No. 1547.

Meng Sun (2021) ‘The Internet and SME Participation in Exports’, Information Economics and Policy 57.

Nayyar, G, M Hallward-Driemer and E Davies (2021) At Your Service? The Promise of Services-led Development, World Bank.

UNCTAD (2018) Power, Platforms and the Free Trade Delusion, Trade and Development Report.

World Bank (2021) Data for Better Lives, World Development Report.