In a nutshell

Over the period from 1980 to 2016, the average regional manufacturing TFP increased by nearly 4%: this reflects an overall increasing trend in manufacturing TFP across MENA countries.

Egypt and Iran were consistently among the top performers in the region: based on the most recent year with available data, they were the only MENA countries that were part of the upper half of top performers worldwide.

Despite the positive trend, the region is behind compared with other regional groups and the world as a whole – a result of its poor performance in areas that are crucial for productivity in the manufacturing sector, plus severe macroeconomic imbalances.

The repercussions of the manufacturing sector for the wider economy are numerous. For a start, it is a stimulator of other economic activities: an increase in manufacturing expenditure leads to an increase in demand for intermediate goods produced by various sectors. The manufacturing sector is also a source of foreign currency through the exports channel. Moreover, the sector’s development requires investments in infrastructure and human capital, which are likely to have positive effects on the competitiveness of the economy.

For such an export-oriented sector, technological progress is particularly important because it ensures competitiveness. In neo-classical growth theory, output growth rate is determined by changes in physical capital, labour and total factor productivity (TFP). TFP is the portion of output growth that is attributed to technological progress.

Given its importance in the manufacturing sector in promoting output growth, recent research has investigated TFP at the firm and industry level among MENA countries (Chaffai and Plane, 2006; Daoud and Sekkat, 2017; Elshennawy and Bouaddi, 2018; Seleem and Zaki, 2021).

Our recent study (Harb and Bassil, 2021) derives TFP levels in the aggregate manufacturing sector of 63 countries over the period from 1980 to 2016 (using the UNIDO, INDSTAT 2 database). Our method is based on Eberhardt and Teal (2020), which generates TFP from estimating country-specific production functions accounting for cross-country correlations.

Based on our research, we show here the evolution of manufacturing TFP across eight MENA countries. The performance of MENA is benchmarked against the world and other regional groupings.

The manufacturing sector in MENA: a brief overview

According to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database, the manufacturing sector’s value added as a percentage of GDP in the MENA countries increased from 7.6% in 1975 to 11.73% in 1988. It then steadily decreased to a trough of 10.85% in 1993, but overshot to a peak of 15.46% in 2001.

This share has been decreasing since 2001 and reached 12.37% in 2020. It is below the world share (16.51%) and lags behind the East Asia and the Pacific (23.16%), South Asia (13.28%), and Latin American and the Caribbean (13.06%) regions.

The three MENA countries with the highest average share over the period from 2000 to 2020 are Jordan, Egypt and Morocco. Moreover, on average, employment in the manufacturing sector as a percentage of total employment was the highest in Tunisia (12%) and Bahrain (13%) over the last two decades.

Finally and based on 2020 figures, compared with all other geographical regions, MENA has the lowest share of manufactured exports in total merchandise exports (23.42%).

Manufacturing TFP in MENA

Based on our findings, Table 1 shows that Egypt and Iran were among the top three performers with respect to TFP in the manufacturing sector in both the base year (1980) and final year (2016). Jordan experienced a substantial improvement as it came third in the final year, up from seventh position in 1980. West Bank and Gaza was trailing in the ranking both in the base and final years. Only Egypt and Iran were part of the upper half of top performers worldwide in the final year, whereas the rest of the countries were among the lower half of performers.

Table 1 Ranking of countries based on base year and final year TFP values

Note: i) base year is 1980 for all countries except for Morocco (1985), Oman (2005) and West Bank and Gaza (1994); ii) final year is 2016 for all countries except for Egypt, Iran and Tunisia (2015), and Morocco (2013); iii) the overall rank is based on our entire sample of 63 countries; iv) countries located in the third quartile are topped by 25% of the sample countries, countries located in the second quartile are topped by 50% of the sample countries, and countries located in the first quartile are topped by 75% of the sample countries.

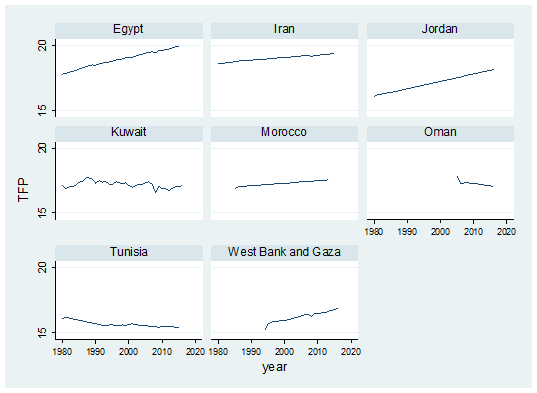

Figure 1 illustrates the time evolution of TFP for each of the eight MENA countries. Overall, countries witnessed an upward trend over the period. West Bank and Gaza registered the highest average annual growth rate (0.48%), followed by Jordan (0.34%) and Egypt (0.33%). Iran, Kuwait, Morocco and Tunisia registered relatively moderate to weak average annual growth rates, while Oman experienced a negative average growth rate per annum.

Figure 1 Time evolution of TFP, by MENA country

Table 2 sheds light on the base and final year TFP values across the MENA countries. TFP has increased over the period for most of the countries, pulling upward the regional average TFP value. The increase in the standard deviation across the period reveals that individual TFP values became more scattered around the regional mean over time, hinting at increasing disparities in terms of productivity within the region.

Table 2: Base year and final year TFP values, by country

Note: i) the average TFP is the simple regional mean value of TFP (sum of the TFP values divided by the number of MENA countries); ii) the standard deviation is a measurement of the dispersion of individual TFP values around the regional mean TFP: the smaller the standard deviation, the more centred are the TFP values around the mean and vice versa.

Figure 2 reports mean TFP values (for base and final years) across several country groupings.

Figure 2: Base year and final year average TFP values, MENA and other groups of countries

Note: i) for each group and year, we report the simple mean TFP value; ii) ‘World’ regroups the 63 sample countries; iii) ‘Asia’ includes 12 countries from East and South Asia; iv) ‘Middle income countries’ includes 24 countries (including six MENA countries) categorised as middle income countries as per the World Bank classification; v) ‘MENA’ includes our sample of eight Middle East and North African countries.

Despite the uptick between the two years, an evident gap still separates MENA from other regional blocs. Further, when compared with the group of middle-income countries, the MENA region also performs poorly. This suggests that MENA countries are underperforming in terms of productivity in the manufacturing sector.

Concluding thoughts on the underperformance of MENA

Recent research has identified some key TFP determinants (at the firm and industry levels) in the MENA region: the share of exports in output produced, foreign investment, lending rates, the tax burden, the time to enforce contracts, usage of information and communications technologies (ICT), spending on research and development, and technological intensity. Table 3 sheds light on proxies for such TFP determinants in the eight MENA countries, and shows that they perform poorly and lag behind Asian countries.

Table 3: Selected TFP determinants

Note: i) source: the World Bank, the World Development Indicators database; ii) all determinants, except the last one, are expressed as average values over 1980-2016; iii) the values reported for the last determinant are the latest ones available; iv) Asia regroups the same 12 East and South Asian countries as in Figure 2.

In addition to the above factors, MENA countries are currently facing macroeconomic constraints. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2021), the outbreak of coronavirus added more strains on the labour market, which was already characterised by high unemployment rates.

To mitigate the impact of the pandemic, many MENA countries increased fiscal packages. But the drop in oil prices in 2020 and the contraction in aggregate demand lowered government revenues, which led to fiscal imbalances and an increase in public debt. Such macroeconomic imbalances are impeding manufacturing TFP growth in the region.

Finally, it is worth noting that with the advent of the digital economy, the ICT sector (and services more generally) is regarded as the (new) backbone of the economy. Nayyar et al (2021) argue that the use of ICT transformed the world of business by expanding economies of scale, stimulating innovation and increasing linkages between businesses. Other research shows that the services sector plays a major role in achieving growth convergence between countries (Akram et al, 2019).

At the MENA level, research suggests that ICT has significantly affected economic growth (Harb, 2017). MENA policy-makers would thus gain by designing and implementing national ICT strategies, as this would positively affect the manufacturing sector and the economy as a whole.

Further reading

Akram, V, PK Sahoo and BN Rath (2020) ‘A sector-level analysis of output club convergence in case of a global economy’, Journal of Economic Studies 47(4): 747-67.

Chaffai, M, and P Plane (2006) ‘Total factor productivity of Tunisia’s manufacturing sectors: measurement, determinants and convergence towards OECD countries’, CERDI Working Paper 200622.

Daoud, Y, and K Sekkat (2017) ‘Cross-country comparative analysis of SMEs’ TFP in MENA region: a firm-level assessment’, Middle East Development Journal 9(1): 55-83.

Eberhardt, M, and F Teal (2020) ‘The magnitude of the task ahead: macro implications of heterogeneous technology’, Review of Income and Wealth 66(2): 334-60.

Elshennawy, A, and M Bouaddi (2018) ‘Sources of heterogeneity in labor productivity and total factor productivity in Egyptian manufacturing’, ERF Working Paper No. 1276.

Harb, G (2017) ‘The economic impact of the Internet penetration rate and telecom investments in Arab and Middle Eastern countries’, Economic Analysis and Policy 56: 148-62.

Harb, G, and C Bassil (2021) ‘TFP in the manufacturing sector: insights from a new dataset based on macro panel estimations’.

IMF, International Monetary Fund (2021) ‘Arising From the Pandemic: Building Forward Better’, Regional Economic Outlook (Middle East and Central Asia).

Nayyar, G, M Hallward-Driemeier and E Davis (2021) ’At Your Service? The Promise of Services-Led Development’, World Bank.

Seleem, N, and C Zaki (2021) ‘On modelling the determinants of total factor productivity in the MENA region: a macro-micro firm-level evidence’, International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management 32(2): 147-78.