In a nutshell

Several Arab League members and MENA countries have been recently characterised by high inflation and large nominal exchange rate movements, concomitantly with a high intensity of civil conflicts.

Civil conflicts lead to real effective exchange rate overvaluations in the region.

Currency overvaluations can hamper post-conflict transitions and affect the emerging institutions, leaving an enduring imprint on the development prospects of the country.

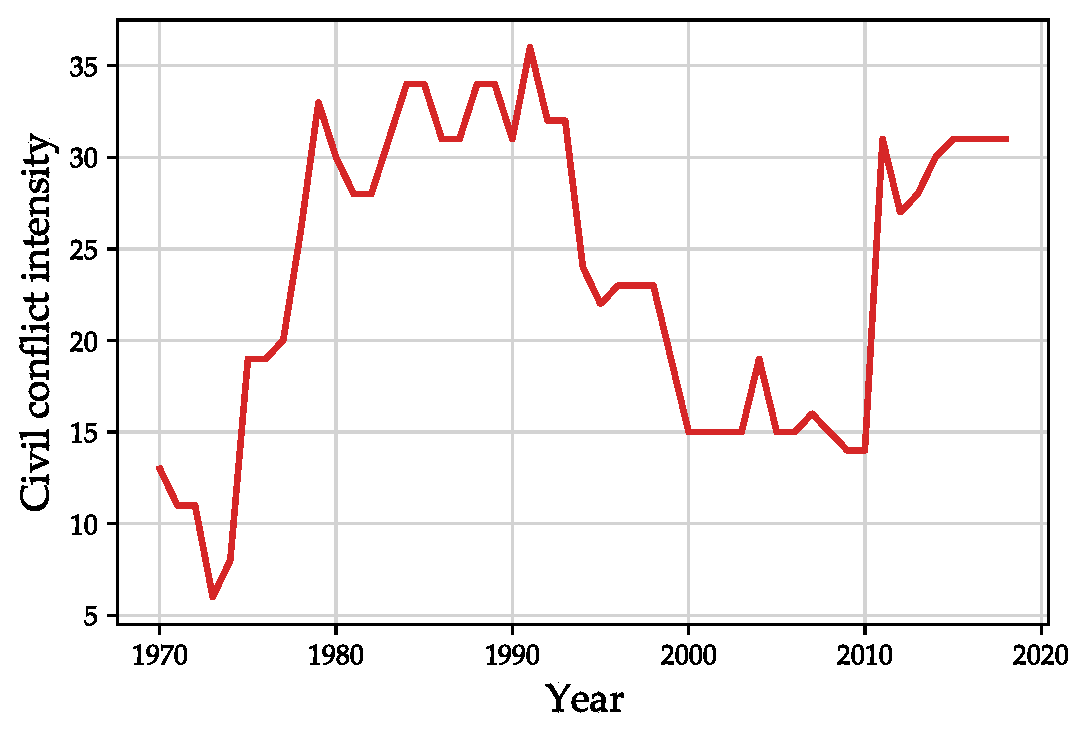

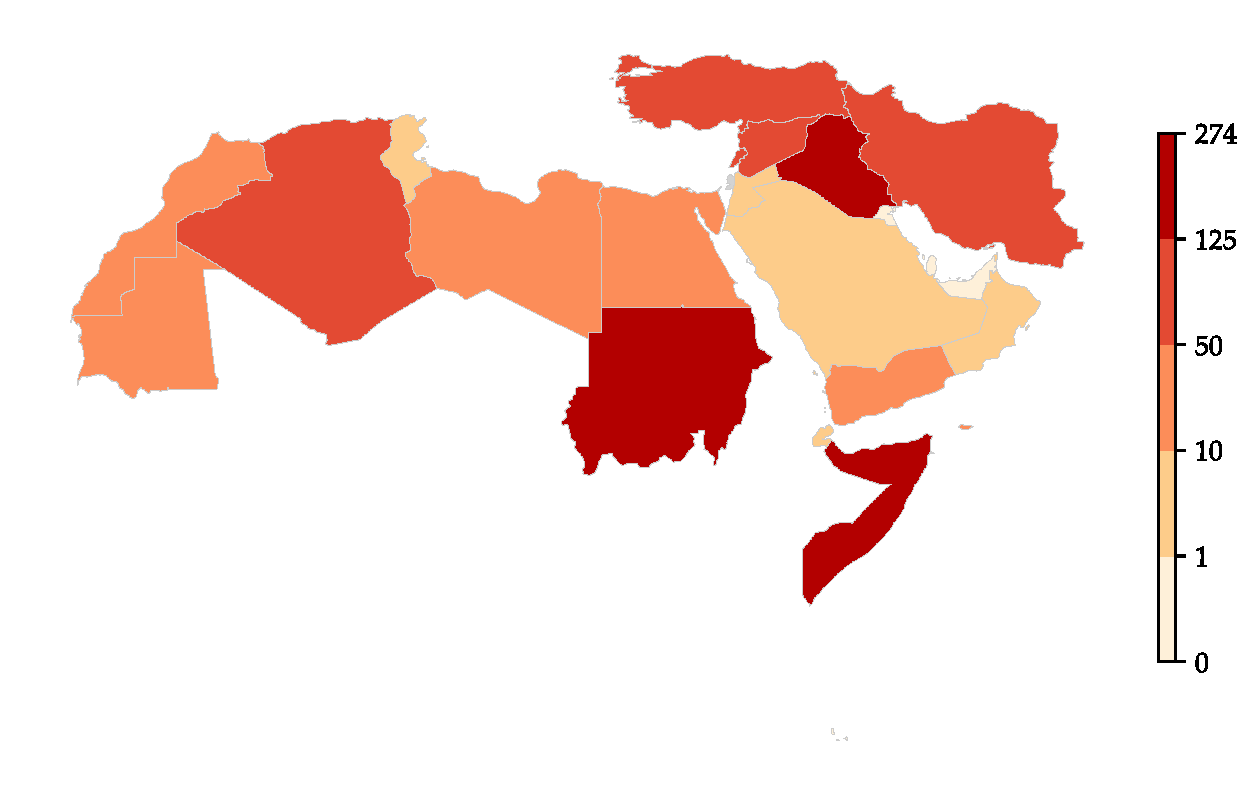

Member states of the Arab League and the MENA region more broadly have long been plagued by civil conflicts. As Figure 1 shows, the intensity of civil conflicts has increased dramatically following the Arab Spring and has reached a level comparable to that of the 1980s. The vast majority of countries in the region have experienced such episodes since the 1970s, albeit to varying degrees.

Figure 1: Civil conflict intensity in Arab League members and MENA countries

a. Aggregate civil conflicts intensity

b. Civil conflicts intensity across countries

Source: Center for Systemic Peace, elaborated by the author. The country-year conflict intensity index takes values between 0 (lowest) and 10 (highest).

Concomitantly, several countries in the region have experienced episodes of high inflation and large nominal exchange rate movements. For example, Iraq, Libya, Sudan and Syria all devaluated their currency in 2021. These phenomena seriously threaten the macroeconomic stability of the countries where they occur, as well as the capacity of their most vulnerable citizens to access basic goods and services.

The adverse consequences of civil conflicts for human development, physical capital and the real sector have been extensively studied by researchers, following Collier (1999) and others. But relatively less attention has been paid to the implications of such conflicts for the monetary and financial sectors.

Historical evidence suggests that this dimension is a key element of civil conflicts. During the US civil war, the then Secretary of the Treasury secured three bank loans of fifty million dollars each to ensure access to gold, and therefore to much needed imports (Mehrling and Sandilands, 1999).

In this context, understanding the effects of civil conflicts on the real exchange rate (RER) proves important since it can affect not only the evolution of the conflict, but also the dynamics of the post-conflict transition. For example, Béreau et al (2012) find that an overvalued RER can lead to lower GDP growth.

In recent research (Lemaire, forthcoming), I construct a real effective exchange rate (REER) misalignment index for Arab League member states, Iran and Turkey, and I assess whether civil conflicts lead to REER misalignment in the region.

Civil conflict can affect the misalignment through various channels, and the overall effect appears to be undetermined. Foreign aid and capital inflows can drop during these events due to lower development and growth prospects. Agricultural output and exports can also decrease during civil conflicts, while demand for military and security goods, as well as imports, are expected to increase. All these mechanisms might lead to a REER depreciation.

In contrast, several other mechanisms suggest that civil conflicts can lead to a REER appreciation. Public spending usually increases during civil conflicts to meet social demands or to organise the war effort, and this can lead to an expansion of the monetary base. The resulting inflationary pressures can be strengthened by the shortages in basic goods supply.

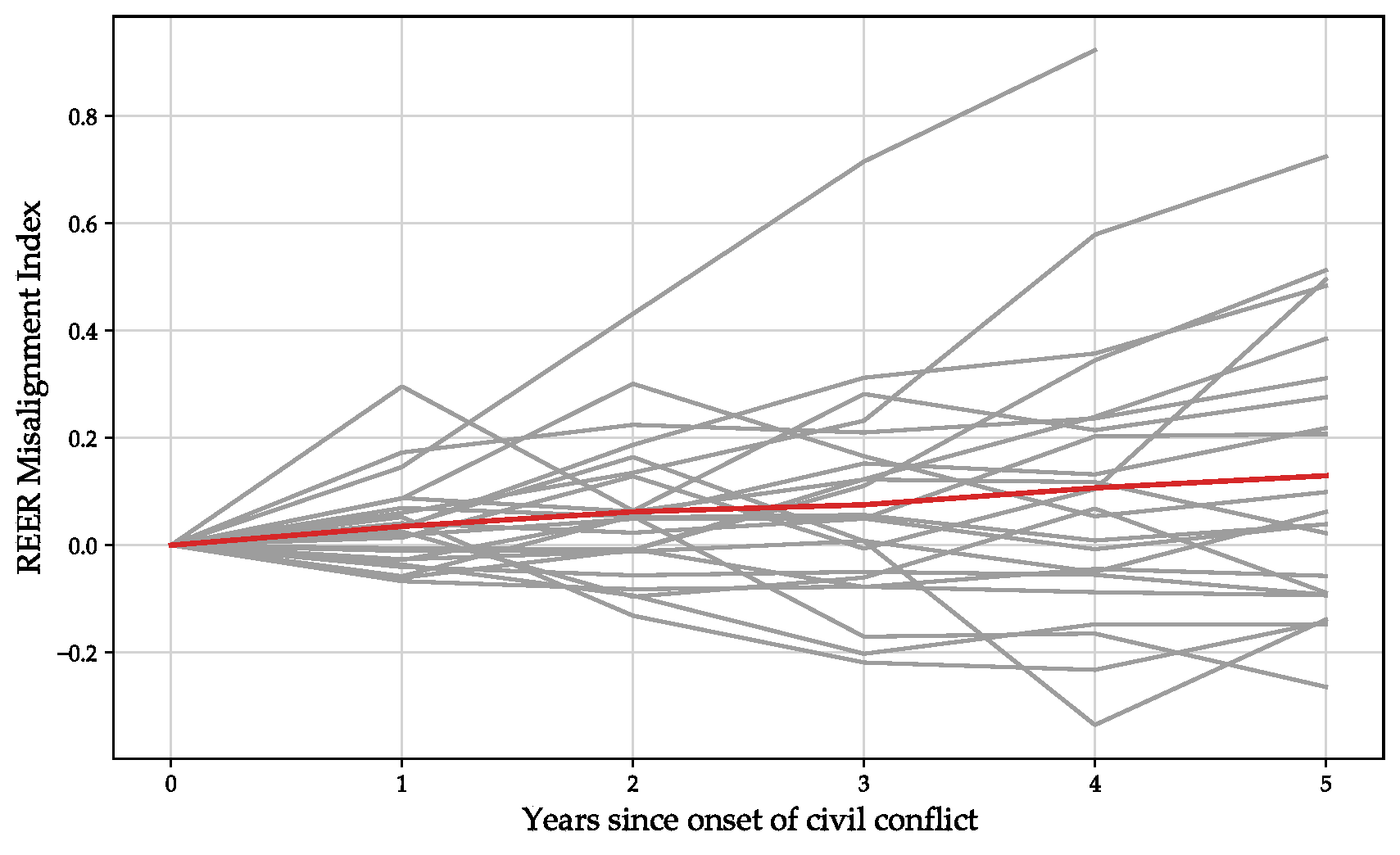

Figure 2: Real effective exchange rate misalignment following a civil conflict onset

Source: elaborated by the author from Lemaire (forthcoming). The red line denotes the average REER misalignment index.

The empirical results indicate that civil conflicts lead to REER overvaluations in the region: the REER misalignment tends to increase. Figure 2 shows the evolution of REER misalignment up to five years after the onset of a civil conflict in some countries of the region and provides evidence of the average increase in REER misalignment following a civil conflict onset.

To ensure the robustness of this relation, I instrument the intensity of civil conflict in a given country by the intensity of civil conflicts in neighbouring countries. This strategy is made possible since civil conflict in a country has potential security spillovers on its neighbours. The results show, however, that it is not possible to differentiate between the effects of civil violence and civil warfare.

Policy implications

Human losses are the first and more direct consequences of civil conflicts. From an economic standpoint, this loss in human capital combines with losses in physical capital to hamper the future growth path and development prospects of the country. But civil conflicts affect long-term prospects in several other ways.

Institutions show a high level of persistence over time. Because the end of a civil conflict and the initial stages of the post-conflict transition define a new, or renewed, distribution of power and set the foundations of the institutions that will ensure its stability (see, for example, Fergusson et al, 2021, and Makdisi and Soto, 2020), the economic conditions and the social context that prevail during these crucial periods may weigh heavily on their outcome. They may be decisive in ensuring sustainable growth and long-term development.

REER overvaluation resulting from civil conflicts can therefore have enduring economic impacts, way beyond the business cycle. ElBadawi and Refaat (2015) show that RER undervaluation tends to be pro-poor in normal times. Because the disorganised productive sector cannot meet the demand, imports are likely to play a significant role in the early stages of reconstruction, and this is particularly important for food products.

In this context, the sharp nominal exchange rate depreciation arising from a RER overvaluation or, under a fixed exchange rate regime, the high inflation and the likely high black-market premium would represent a heavy burden on the poorest and directly threaten their very subsistence.

The resulting discontent and social unrest could threaten the post-conflict transition itself, or indirectly shape the emerging institutions in a way that tends to allocate efforts and capacities to security organs at the cost of reconstruction and growth promotion, leaving an enduring imprint on the development prospects of the country.

Further reading

Béreau, S, AL Villavicencio and V Mignon (2012) ‘Currency Misalignments and Growth: A New Look Using Nonlinear Panel Data Methods’, Applied Economics 44(27): 3503-11.

Collier, P (1999) ‘On the Economic Consequences of Civil War’, Oxford Economic Papers 51: 168-83.

ElBadawi, IA, and E Refaat (2015) ‘Competitive Real Exchange Rates Are Good for the Poor: Evidence From Egyptian Household Surveys’, ERF Working Paper No. 966.

Fergusson, L, P Querubin, NA Ruiz and JF Vargas (2021) ‘The Real Winner’s Curse’, American Journal of Political Science 65: 52-68.

Lemaire, T (forthcoming) ‘Civil Conflicts and Exchange Rate Misalignment: Evidence from MENA and Arab League Members’, ERF Working Paper.

Makdisi, S, and R Soto (2020) ‘Economic Agenda for Post-Conflict Reconstruction’, ERF Working Paper No. 1395.

Mehrling, PG, and RJ Sandilands (1999) Money and Growth: Selected Papers of Allyn Abbott Young Vol. 29, Routledge.

The views expressed in this column and the research paper that is summarises are those of the author and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of Banque de France or the Eurosystem.