In a nutshell

There are significant spillovers in productivity across industries in Turkey as a consequence of industries’ interconnectedness through input-output linkages.

Participation in global value chains (GVCs) plays a central role in explaining changes in productivity at the industry level: productivity rises with forward linkages – export of inputs used in the export of another country’s export to third countries – and declines with backward linkages – imported intermediates used in exports.

As a result of spillover effects, there are significant indirect effects of participation in GVCs on productivity; for example, productivity increases with forward linkages both within and across industries.

With advances in transport and communication technologies, improvement of infrastructure facilities and falling trade barriers, the process of international economic integration has been rapidly growing, organised around the concept of global value chains (GVCs). Access to new modes of specialisation has induced firms to slice production into tasks performed at different locations to optimise their factor costs (Feenstra and Hanson, 1997; Grossman and Rossi Hansberg, 2008).

The impact of GVCs on economies has been explored for some key outcomes such as employment, productivity and knowledge spillovers. For example:

- A study by Constantinescu et al (2019), which uses a sample of 40 countries and 13 manufacturing industries, finds that GVCs boost productivity.

- Baldwin et al (2014) find that productivity gains associated with GVCs may accrue from different channels such as increases in competition, access to a variety of inputs, learning externalities and technology spillovers.

- And using inter-country input-output tables, Kummritz (2016) finds that labour productivity significantly rises with GVC forward linkages – that is, the export of inputs used in the export of another country’s export to third countries – but is not significantly associated with backward linkages – imported intermediates used in exports.

While cross-border spillovers in productivity have been widely studied, few have explored spillovers between industries. Balassa (1961) argues that linkages between sectors are key sources of productivity spillovers and that the magnitude of the spillovers is amplified by transmission of technological improvements. This suggests the importance of examining spillovers in productivity.

In this column, we examine the Balassa hypothesis in the case of Turkey. We also examine the impact of the participation of Turkish industries in GVCs on productivity under such a configuration.

Turkish industries’ participation in global value chains

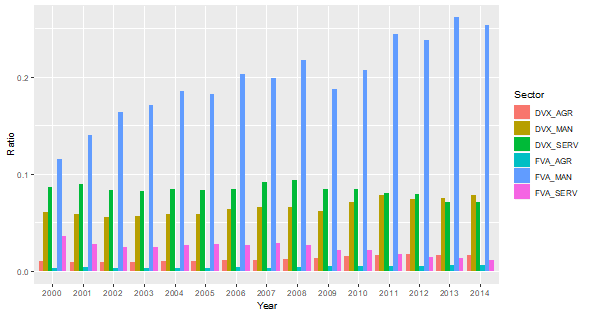

Figure 1 plots changes in the backward and forward linkages variables as a share of gross exports for three sectors’ categories: agriculture (AGR), which encompasses all primary products-based sectors including agriculture, forestry, fishing and mining; manufacturing (MAN) and services (SERV).

Manufacturing sectors seem to be the most linked to GVCs via backward linkages and increasing faster over the period studied. Agriculture sectors’ backward linkages are the smallest. Service sectors’ linkages via forward linkages are the highest and increased the most, followed by manufacturing forward linkages, while th agriculture sectors lagged behind.

Figure 1. Backward and Forward linkages by sector, from 2000-2014

Source: Mohamedou (2019)

Productivity spillovers in Turkey

My recent study (Mohamedou, 2020), which uses world input-output tables, shows that productivity in Turkish industries is susceptible to significant spillovers effects as a result of industries’ interconnectedness via input-output linkages and that the magnitudes of the spillovers depend on the degree of connections between industries. The spillovers effects are more pronounced for manufacturing industries compared with service and agriculture industries.

This finding is consistent with Balassa’s (1961) view on horizontal and vertical linkages between industries as a key source of productivity spillovers and that the magnitude of the spillovers is amplified by the transmission of technological improvements.

This result is central for policy-makers as most of the existing studies ignore the spillovers effects across industries. There are hardly any studies on productivity spillovers across industries.

GVC participation and productivity in Turkish industries

The analysis in my study (Mohamedou, 2020), which generates both direct and indirect productivity effects of participation in GVCs, also shows that participation plays a central role in explaining changes in productivity in Turkey at the sector level.

Specifically, I show that forward linkages boost productivity at the sector levels. This is in line with the concept of ‘learning by exporting’, by which firms with export orientation tend to become more productive as a result of the accumulation of learning (De Loecker, 2013).

In contrast, my study reveals that backward linkages – imported intermediates used in exports – are negatively associated with productivity. This can be explained by the fact that imported intermediates act as a substitute for locally produced goods, which leads to a declining value-added and, thus, productivity.

Indirect effects of GVC participation on productivity

The indirect effects of GVCs rise as a result of spillovers through industries’ input-output linkages. In other words, changes in one of the GVC indicators will affect productivity both within and across industries. This result is central for understanding the total effects of GVC participation on productivity (see Mohamedou, 2020, for more details).

Productivity in Turkish industries is prone to significant indirect effects of GVC participation. In particular, productivity rises together with forward linkages both within and across industries, whereas no indirect effects of backward linkages are found.

All in all, the implications of GVC participation for productivity in Turkey, ignoring spillover effects between industries as a consequence of input-output linkages between industries, is to be reconsidered.

Moreover, there are significant spillovers effects in productivity across Turkish industries, which lend support to the Balassa (1961) hypothesis. The spillovers seem to transmit as a result of industries’ input-output linkages. Consequently, policies aiming at identifying channels through productivity as well as knowledge spillovers should consider the interconnections between industries.

Further reading

Balassa, B (1961) ’Towards a Theory of Economic Integration’, Kyklos 14(1): 1-17.

Baldwin, Richard, and Anthony J. Venables (2013) ‘Spiders and snakes: offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy’, Journal of International Economics 90(2): 245-54.

Constantinescu, C, A Mattoo and M Ruta (2019) ’Does Vertical Specialization Increase Productivity?’, The World Economy.

Feenstra, RC, and GH Hanson (1996) ‘Globalization, Outsourcing, and Wage Inequality’, American Economic Review 86(2): 240-45.

Grossman, Gene M, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg (2008) ‘Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring’, American Economic Review 98(5): 1978-97.

Mohamedou, ND (2019) ‘Impact of Global Value Chains’ Participation on Employment in Turkey and Spillovers Effects’, Journal of Economic Integration 34(2): 308-26.

Mohamedou, ND (2020) ‘Inter-Industry Spillovers in Labor Productivity and Global Value Chain Impacts: Evidence from Turkey’, ERF Working Paper No. 1430.

Kummritz, V (2016) ‘Do Global Value Chains Cause Industrial Development?’, CTEI Working Paper No. 2016-01.