In a nutshell

Covid-19 offers a window for reform to rebuild Egypt’s social safety net – to quote a well-known phrase about seizing opportunities in challenging times, ‘we should never waste a good crisis’.

A negative income tax would make the Egyptian economy more resilient to an economic shock; it would offer potential assistance to reduce informality and it would help to eradicate extreme poverty.

The fact that the Government of Egypt has already disbursed cash assistance last year shows that it has the administrative capacity to operate a programme like a negative income tax.

The Covid-19 crisis has shown clearly the weakness of social safety nets in developing economies. According to the World Bank, global extreme poverty (people living on less than $1.90 a day) rose in 2020 for the first time in many years. The crisis is expected to push as many as 150 million people into extreme poverty by this year.

Thanks to strong growth in consumption, which offset the impact of weak tourism and investments, Egypt was able to maintain its economic growth rate in positive territory. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Egyptian economy grew by 3.6% in the financial year 2019/20 and is projected to grow by 2.8% for 2020/21.

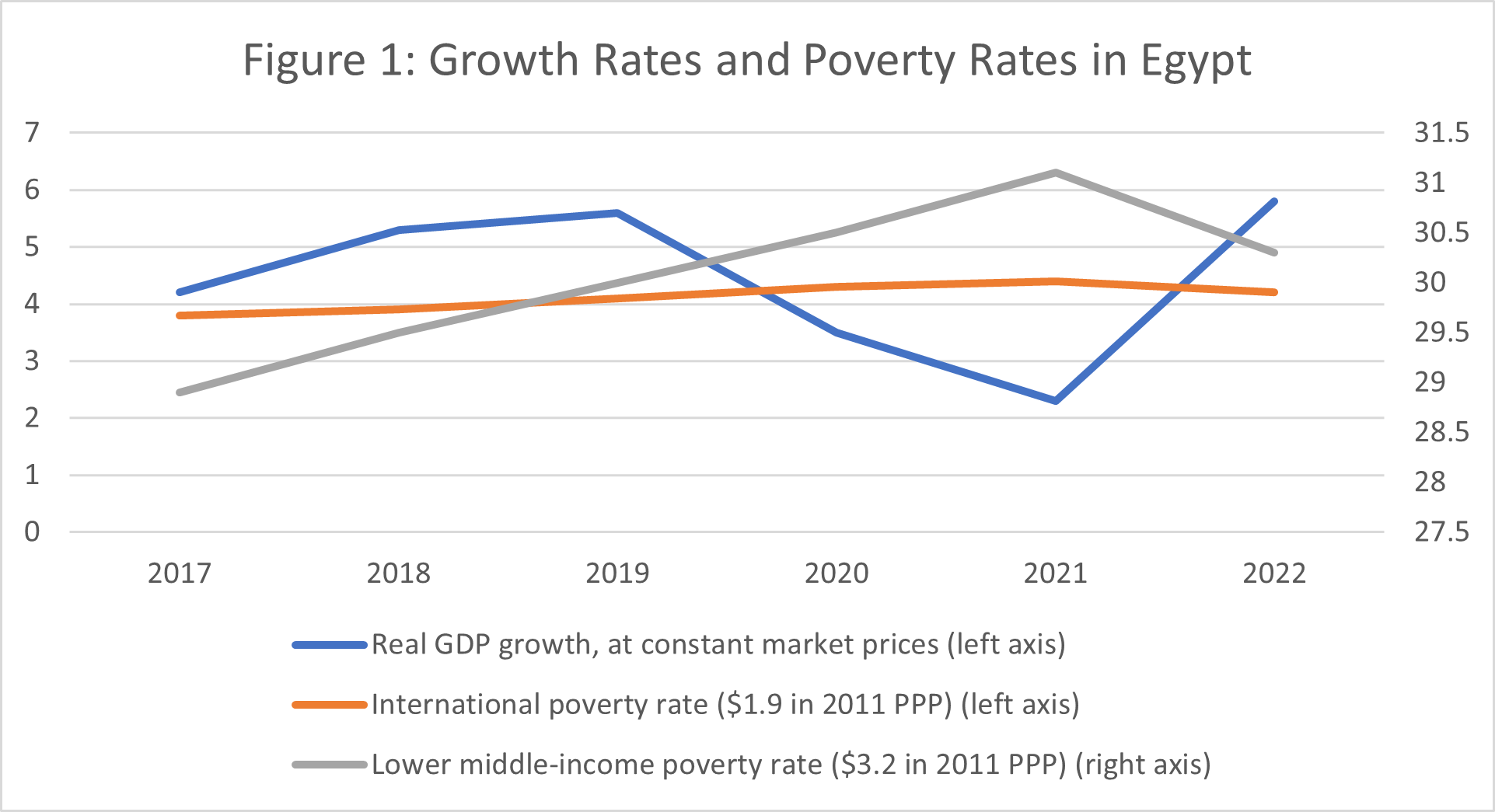

But the impact of the crisis on the poor and ‘near-poor’ might be less bright. According to the World Bank’s Macro Poverty Outlook, extreme poverty marginally increased in 2020 and is forecast to reach its highest level since 2017 this year and to start falling in 2022 as the economy is expected to rebound strongly in 2021/22. A similar observation applies, an inverted V, for the lower-middle-income poverty rate – see Figure 1.

Source: World Bank Macro Poverty Outlook

To shield the most vulnerable from the Covid-19 crisis, the Government of Egypt provided irregular workers with a monthly allowance of 500 Egyptian pounds (EGP, equivalent to about US$66 measured in ‘purchasing power parity’, PPP) cash for about eight months.

The fact that the government has taken steps to disburse money to vulnerable workers raises the question: why not capitalise on this momentum and turn the policy into rules-based fiscal stimulus – where the stimulus is automatically activated by a weakening in key economic indicators.

One way of converting the temporary cash assistance policy into a rules-based fiscal stimulus or an automatic stabiliser that can strengthen the resilience of the Egyptian economy to downturns is a negative income tax. It is a possible and affordable dream, and can be an effective and timely way to counter negative shocks. The Egyptian economy lacks automatic stabilisers that cushion the poor and unemployed during downturns such as unemployment insurance or other household benefits.

A negative income tax, which was first suggested by economics Nobel laureate Milton Friedman, is a system that pays a subsidy to low-income workers and the unemployed if their income is below a stipulated level (the tax exemption limit). Under a negative income tax, low-income workers who earn less than the tax exemption limit are eligible to get transfer equal to the gap between their incomes and the minimum income, and the income transfer declines as income increases.

Thus, in the case of Egypt, if we set the minimum guaranteed income just equal to the extreme poverty line (EGP 5,889.60), then an unemployed person will receive US$2 PPP a day, barely enough to cover their needed calories. According to the tax law, the individual income tax rate exemption in Egypt is equal to EGP 15,000 (US$2,000 PPP) per year.

If the negative tax rate is set at minus 40% for the poor and near-poor, then an individual with an annual income of EGP 12,000 (EGP 1,000 monthly or US $4.3 PPP a day) would receive EGP 1,089 or US$0.39 PPP per day from the government as a living supplement. When a person earns more than the tax exemption limit, the positive tax rate would apply, as is the case now.

According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), about four million Egyptians work in the informal sector. They do not have a work contract, health insurance or social security – and they do not pay taxes.

A negative income tax may provide additional incentives for informal workers to get formalised, as they see a direct benefit from formalisation – that is, a cushion from extreme poverty during downturns or income supplement for workers in hardship. Thus, a negative income tax offers no sticks but only carrots to informal workers.

The public finances might also benefit from a negative income tax as new taxpayers enter the tax system, and as the economy rebounds and productivity improves, less cash assistance might be needed. A negative income tax might also provide a window for the government to regulate the informal sector. In addition, a negative income tax could have positive externalities for society, as it may reduce criminal activity that is associated with high unemployment or child labour, or reduce fertility that is used as a social protection mechanism.

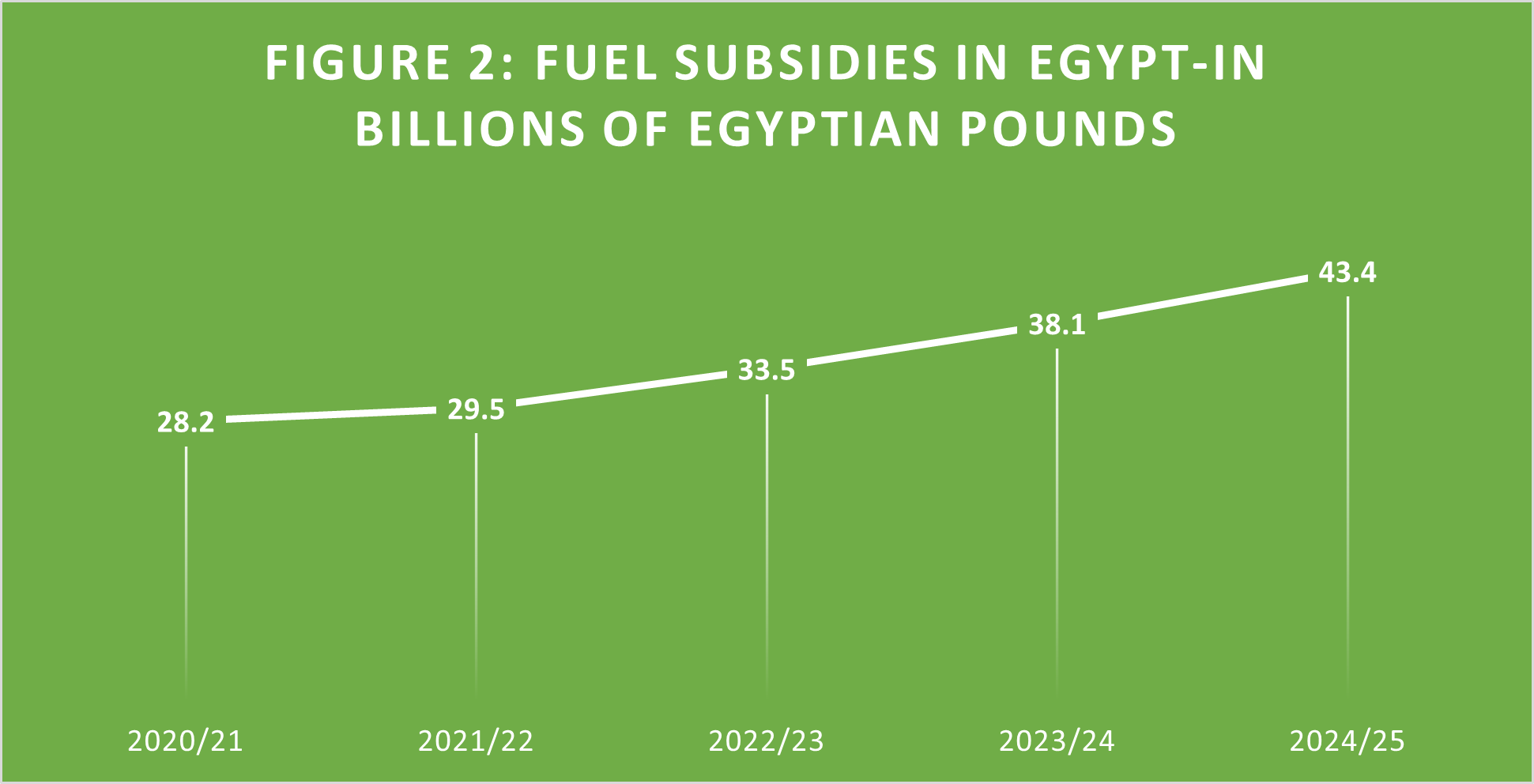

While some countries are considering a carbon tax, the Government of Egypt is still subsidising fuel. According to the IMF, the government subsidised fuel by 0.4% of GDP in 2020/21, equivalent to EGP 28.2 billion. At the same time, the latest estimate of the extreme poverty gap is about EGP 22 billion. Thus, a negative income tax might be funded, at least partially, from fuel subsidies or even if the government considers a carbon tax to reduce emissions.

On the other hand, providing a very small cash assistance equivalent to the extreme poverty line (at the maximum) will not deter anyone from working or affect the labour supply. To reduce the inefficiency that is associated with any redistribution policy, the government could mandate some conditions. For example, new entrants (informal workers) to the tax system could only benefit from the negative income tax after some time from enrolment, one year for example, and the subsidy may have a maximum duration of time.

Source: IMF Projections

In conclusion, a negative income tax will make the Egyptian economy more resilient to an economic shock. In addition to its positive externalities, it might offer potential assistance to reduce informality in the Egyptian economy, and it will help in eradicating extreme poverty.

The fact that the Government of Egypt has already disbursed cash assistance last year shows that it has the administrative capacity to operate a programme like a negative income tax. Maybe Covid-19 offers a window for reform to rebuild our social safety net – and to quote a well-known phrase about seizing opportunities in challenging times, ‘we should never waste a good crisis’.

Further reading

International Monetary Fund (2021) ‘Egypt: First Review Under the Stand-by Arrangement’.

World Bank (2020) ‘Macro Poverty Outlook’.