In a nutshell

Lebanon’s government and the Banque du Liban have mismanaged the economy and the financial markets: the fact that the hard landing took this long is extraordinary.

Capital controls imposed by the banks can be expected to remain in effect until the government has restructured the public debt, restored confidence in the public sector and taken rigorous measures to redress the balance of payments.

The gradual lifting of controls cannot happen any time soon, since many depositors, political leaders and corrupt business people will try to move their money out of the country.

Lebanon’s national currency has been spiralling down against the US dollar for several months (Mora, 2020) and continues its free fall at the time of writing. Billions of dollars have recently fled the country; simultaneously, the central bank has implicitly imposed some strict capital controls. Prices of basic goods have skyrocketed, destroying many aspects of the economy; and the country is experiencing malls closure, negative growth, environmental degradation and massive public unrest.

Economic factors and policies

First, this crisis is essentially a governance crisis emanating from a broken sectarian system that stalled rational policy-making and allowed a culture of corruption and waste. Lebanon’s historically fragile government has depended on increasing public debt to square its payments, while failing to accomplish reforms that could have reinforced its economy and increased international investment.

This turned Lebanon into the third most indebted state in the world. Such large and growing annual financing needs made the country more vulnerable to external shocks. As external financial flows into Lebanon slowed, the central bank resorted to desperate and expensive efforts to attract dollar deposits to maintain the currency peg and to finance the government’s purchases.

Lebanon witnessed a turning of the balance of payments into negative territory from 2011. The current account balance’s constant drop for several years now signalled that Lebanon was losing foreign currency reserves to the rest of the world.

This relatively new development in the balance of payments is exceptional and has not been experienced since Lebanon’s independence. Remittances from abroad, with a large diaspora, historically have been instrumental in addressing the current account deficit caused by the balance of trade deficit. They started to dwindle from 2011 because the global financial crisis and political affiliations limited the ability of senders to make such transfers.

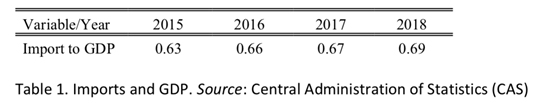

Table 1 shows the growing and very large size of imports relative to GDP: close to two-thirds of GDP. Exports are negligible and dwindling relative to GDP, which has contributed to a high trade deficit.

The credible peg to the US dollar that prevailed from 1998 permitted domestic consumers to deposit earnings in Lebanese pounds (LBP), and use them for imports, giving rise to conspicuous and luxury consumption. There was almost no private investment in local manufacturing or agriculture. This excessive consumption was unsustainable without foreign currency inflows.

Political corruption

Sectarianism has long constrained Lebanese politics since the French mandate. This has been an important contributor to the rampant corruption. High-ranking government officials, because of their political and religious affiliations, felt immune from judicial prosecution, inflated expenses, hired relatives as consultants to increase the size of the government to unprecedented proportion, contributing to the public deficit.

Adding to the ‘misery index’ are high unemployment and inflation. The main challenge here is that too many public officials are involved in corruption. It will take a solid political will and a sovereign central government to reform public governance, which currently seems remote.

The austerity programme in the 2020 economic plan would increase poverty and unemployment. As long as there is no structural political change that leads to a change in the culture of managing and operating public utilities, mainly electricity, such plans will not work. It does not seem that radical solutions will take place before a competent and independent legislative body is elected with higher moral standing.

The role of the Banque du Liban in the crisis

The Banque du Liban (BDL, the central bank of Lebanon) has not been an innocent bystander during the past two decades. The BDL’s policies and its accommodative tendency towards the Lebanese commercial banks, combined with corrupt practices and chaotic fiscal and monetary programmes, are at the core of the recent crisis.

To understand the free falling LBP, let us look at the fixed exchange rate system that was prevailing prior to late 2019. A fixed exchange rate is only defensible if the economy produces, consumes and trades harmoniously with that rate. The balance of payments deficit led to an outflow of foreign reserves.

There were large and persistent fiscal deficits from the early 1990s, rising government debt coupled with a monetary policy premised on borrowing dollars from banks at high interest rates. As a result, the banks developed a foreign currency asset-liability duration mismatch. This choked private lending, weakened banks and built demand for foreign exchange. By September 2019, many subsidised goods exerted a drag on the BDL’s foreign reserves.

Internal versus external debt

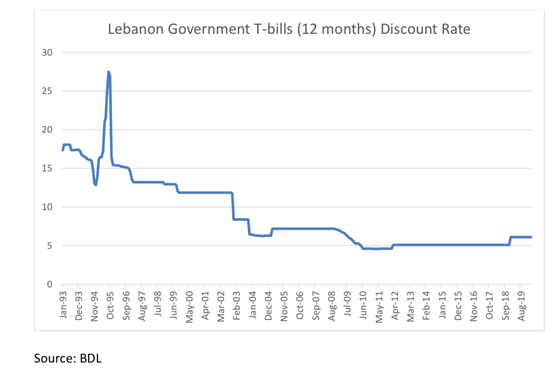

The figure below shows that in the early days of the debt issuance, the rates were astronomical; they fell, oddly, as more debt was issued in later periods. For example, the central bank reports that domestic debt in 1993 was $2.6 billion while foreign debt was only $327 million; these figures grew to $48.5 billion and $34.0 billion by February 2020, respectively.

The borrowing from the private sector strained the government’s funds to service the debt, and raised these payments as a result of increasing interest rates (see February to October 1995).

Interest rates witnessed a downward trend when the currency was successfully pegged to the dollar. The lack of foreign exchange risk should not have raised the interest rates to that level in the 1990s, since they should only rise with the debt. Perhaps the central bank played conflicting roles in directing and supervising T-bills auctions, preferentially treating foreign investors.

During the period 1993-96, the average yield on T-bills outstanding was 21%, while that on Lebanese Eurobonds was 10% (Hakim and Andary, 1997). The government could have reduced its financing cost by borrowing internationally, not domestically. The premium on domestic borrowing supported the operations of banks since they invest heavily in high-yielding T-bills.

Both interest rates should be equal, as the peg was holding and there was no third party explicit guarantee to the foreign debt to make them more secure. But Lebanese banks would not have been as healthy without this generous subsidy from the BDL; the latter may have used this system to strengthen demand for LBP.

Impact on foreign exchange reserves

In addition to the faltering foreign currency reserves at the BDL, the LBP devaluation started in September 2019. The depreciation rate of 400% eroded the wealth of many Lebanese people and hurt small and medium-sized businesses.

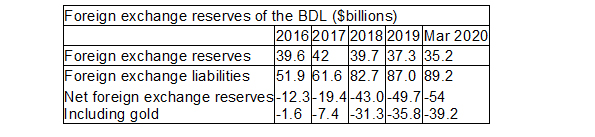

The BDL started using ‘financial engineering’ in 2016 to attract dollars into the country and continue the peg, through offering high rates for LBP accounts and then swapping it with dollars, increased BDL dollar-denominated debt and reduced foreign reserves to negative territory (see Table 2 below).

The BDL aimed at financing budget deficits, and maintain the peg to accommodate public borrowing. Unfortunately, the deficits have financed current expenditures, increasing the size of the public sector, and contributed to the financial deterioration. The size of the loss on these reserves cannot be sustained without some major adjusting inflow of foreign currency into the BDL’s balance sheet.

Table 2. Source BDL – BDL reserves, excluding gold, are foreign-currency reserves deposited in foreign main banks, plus short-term liquid investments. Banking Control Commission.

These practices were carried out under the presumption by the BDL that Lebanon was able to finance its public and private sectors internally without resorting to external funds. Many economists compared this practice to a Ponzi scheme, leading to over-borrowing.

Meanwhile, more than 70% of local banks’ assets financed the public sector, crowding out the private sector’s credit, affecting their liquidity and weakening them financially. Cyprus in 2012/13 offered equity conversion of 48% of uninsured deposits in the Bank of Cyprus: this outcome may occur in Lebanon.

BDL and the government’s management of the crisis

Recently, Covid-19 has added to the economic woes of the country, with the implementation of social distancing resulting in a further reduction in economic activity, especially affecting tourism, taxi drivers and restaurant businesses. The government in the middle of the pre-existing crisis, now found its depleted coffers unable to structure a stimulus package to help the most vulnerable in society to weather the pandemic.

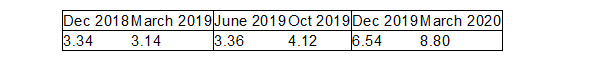

The BDL is currently providing foreign currency to import essentials, with gold reserves unlikely to cover any debt since Law 42 (in 1986) prevents it from selling them without legislation by parliament. The currency crisis has caused the BDL to introduce several exchange rates to manage demand and protect purchasing power; it has injected a large amount of LBP recently into the local economy despite falling demand deposits, partly contributing to very high inflation:

BDL Currency in circulation, ($b. equivalents of LBP at the official exchange rate)

Source BDL monetary aggregates

In March 2020, currency almost tripled year-on-year; this also shows that the Lebanon has mainly become a cash society.

Conclusion

The government and the BDL have mismanaged the economy and the financial markets. The fact that the hard landing in Lebanon took this long is extraordinary.

Recent discussions with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) require economic reforms as a precondition for IMF assistance. The overvalued ‘official’ exchange rate, the untenable external (Eurobond) debt and the excessive public spending may lead to the imposition of tough conditions; but these may spur already existing social unrest.

This process may open the door to donor consultations, and ease negotiations with the creditors. In addition, the government will also be motivated to pursue debt restructuring, mostly held by the central and local banks. Domestically, the IMF bailout may be the only hope to provide needed liquidity for the balance of payments and the BDL.

Looking into the future, a silver lining from the crisis may increase employment of locals in favour of foreigners who are leaving the country; and import substitution may increase locally produced goods.

Capital controls imposed by the banks can be expected to remain in effect until the government has restructured the public debt, restored confidence in the public sector and taken rigorous measures to redress the balance of payments. Iceland spent around nine years before the controls were lifted. In Lebanon, we are looking for a long-term exit from this crisis.

Therefore, the gradual lifting of controls cannot happen any time soon, since many depositors, political leaders and corrupt business people will try to move their money outside Lebanon. Hence, capital controls by the banks may need to be legislated by the government to organise capital flows and restore confidence in the banking sector.

Further reading

Byblos Bank economic research.

Central Administration of Statistics (CAS), Lebanese Republic.

Hakim, S, and S Andary (1997) ‘The Lebanese Central Bank and the Treasury Bills Market’, Middle East Journal 51(2): 230-41.

Mora, N (2020) ‘A Primer on the Financial Crisis in Lebanon: A Historical and Cross-Country Perspective’.