In a nutshell

Despite improvements in public access to household budget surveys, data availability and timeliness remain poor in the MENA region; for some indicators, data availability is even worse than in sub-Saharan Africa.

The key way to fill data gaps in the region is more regular collection of household budget surveys and improving access to existing data; alternative techniques may be used where conducting surveys is not feasible, especially in conflict-affected contexts.

‘Big data’ offer the possibility of alternative ways to measure wellbeing – but researchers should use them cautiously and in conjunction with traditional surveys, where possible.

Having comparable and up-to-date household budget surveys is crucial for monitoring global and regional monetary poverty trends. In our work (Atamanov et al, 2020), we show the extent to which data availability and timeliness are inadequate in the MENA region despite improvements in public access to household budget surveys (HBSs).

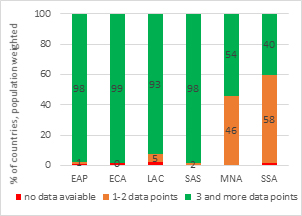

Indeed, data availability is close to the much poorer sub-Saharan Africa region and lags behind the rest of the world. For example, between 2004 and 2018, seven of 13 MENA countries, or more than half the countries in the region accounting for 46% of MENA’s population, conducted fewer than three surveys (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Availability of household budget surveys (measured by poverty data) by region between 2004 and 2018, population weighted in each region

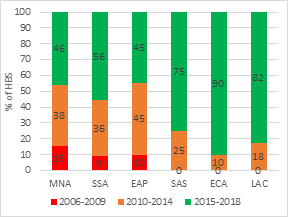

Figure 2. Distribution of the most recent household budget surveys (measured by poverty data) by data collection period

Source: WDI (May 2020) and authors’ calculation.

Note: If survey period bridges two years, the first year serves as a survey year. * average country shares in regional population during 2004-2018 are used as weights. For a comprehensive assessment of available household surveys suitable to measure poverty, we use the number of poverty statistics reported in the World Development Indicators (WDI) database for the last 15 years, 2004 to 2018 (we use both poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day 2011 PPP and national poverty rates including non-comparable ones). In the MENA region, we manually added information about existing household budget surveys in Iran for each year between 2004 to 2018, Jordan for 2017 , Libya for 2007, and Egypt for 2017, countries for which we either have access to microdata or know can be, or were, used to measure monetary poverty but not included in the WDI.

Outdated data are even less useful if a country experiences substantial structural economic changes or shocks. The MENA region does not perform well in this dimension compared with other regions. Thus, more than 50% of the most recent surveys in the region date from between 2006 to 2014, with many of the most recent surveys occurring before large shocks that fundamentally changed the welfare distribution (see Figure 2).

In addition to needing recent HBSs to provide current welfare metrics, comparability of these surveys across time is important to estimate trends. In the absence of at least two comparable data points, it is impossible to analyse poverty or consumption/income growth across time.

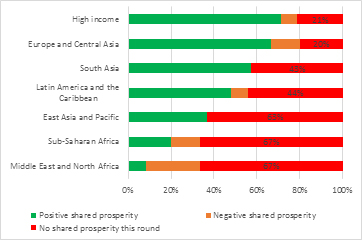

Figure 3 shows shares of countries reported and not reported in the World Bank’s global shared prosperity database. Excluded are those countries that did not have two recent and comparable welfare aggregates. The regions with the highest share of countries not reporting shared prosperity are sub-Saharan Africa and MENA.

Figure 3. Shares of countries reported and not reported in the World Bank’s global shared prosperity database across regions, circa 2012-2017

The priority for filling gaps in measures of wellbeing MENA should include improving access to existing HBSs and more regular collection of HBS data. International organisations, including World Bank, can play a supportive role by providing technical assistance and sharing expertise in data collection, poverty measurement methods, microdata anonymisation, and data sharing practices. International organisations can also provide funding or co-finance microdata collection in countries with limited resources.

If data collection is not possible, one can turn to data imputation techniques to obtain poverty estimates. This approach requires at least one up-to-date consumption survey and a non-consumption survey that collects similar individual and household socio-economic characteristics.

Imputation can be tested in MENA countries with established regular collection of labour force surveys (LFSs). The Covid-19 pandemic can create a structural break in consumption series and may limit possibility of imputation calling for collection of new household budget surveys when lockdown is over.

If collection of new HBSs is not possible, and imputation is not feasible either, measuring non-monetary indicators of wellbeing using non-traditional surveys can be considered. For example, multidimensional poverty indexes (MPIs) can be used to track non-monetary dimensions of poverty.

But constructing MPIs requires information on each deprivation for all households and often for individual household members. This information should be based on micro-level data and should come from one source. This is challenging because it is not easy to find microdata with information on all dimensions of non-monetary poverty.

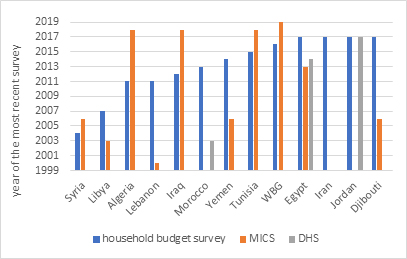

Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are often used for this purpose, but there are few countries in MENA where these surveys are more up to date than HBS surveys (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Latest year of household budget survey, MICS and DHS in MENA countries

Source: Authors’ compilation.

High phone penetration in MENA offers another alternative. Phone surveys can be valuable in conflict settings or other situations (Covid-19) when face-to-face data collection is not possible, and where the population has experienced large and sudden shocks and rapid information is needed.

A key drawback of this method is that the surveys typically represent only the phone-using population. In addition, this mode of data collection allows asking only a short set of questions. Phone surveys can be particularly useful and provide representative picture of phone-using population if respondents are selected from the representative household budget survey.

Using ‘big data’ in the MENA region – such as administrative records, geospatial information, and social networks – can help to measure wellbeing without requiring burdensome face-to-face interactions. This can be particularly useful when collecting traditional data through sample surveys is not possible.

But the main disadvantage of ‘big data’ approaches is that researchers cannot control the population covered, and the data can overlook populations of interest or introduce welfare estimation biases. Restrictions on data access and confidentiality related to administrative records can be further serious constraints. Finally, a lot of ‘big data’ does not have a natural or useful interpretation, but when combined with traditional surveys a useful welfare picture can emerge.

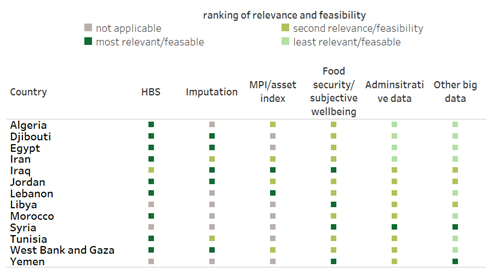

Our study (Atamanov et al, 2020) summarises the discussion of methods/data to fill HBS data gaps in Figure 5, which ranks approaches from the most relevant and feasible to the least relevant and feasible. Higher relevance is associated with darker colour: grey indicates that the method is irrelevant or not feasible in a particular country.

Figure 5. Ranking of different methods and types of data for measuring wellbeing in the MENA countries

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Note: Since the Covid-19 outbreak, the ranking may change since most face-to-face options are not currently available.

Algeria, for example, conducted its latest HBS in 2011, its latest labour force survey in 2014, its MICS in 2017 and its Arab barometer in 2019. Using this information, we ranked different methods and data for measuring wellbeing the following way.

‘Conducting a new household budget survey’ as a top priority, and calculation of an MPI/asset index and measuring subjective wellbeing as second-best options. Alternatively, we note that imputation is not feasible because the existing HBS is too old. Using administrative and big data can help, but it is unclear how we might access credible welfare information.

Overall, collecting new HBS data is a top priority for nine of 13 countries. Imputation is feasible in a number of countries for years they have not conducted HBSs. As expected, conflict-affected countries use different strategies to measure wellbeing, with most relying on non-traditional methods and data.

In summary, the MENA region is facing substantial problems related to the availability and timeliness of HBSs necessary for regular welfare measurement. Priority for the region should be to collect consumption survey data regularly and to improve access to, and the quality of, existing surveys.

Where conducting more HBSs is not feasible – especially in violent and conflict-affected contexts – using alternative non-consumption surveys and imputation techniques may be considered as a second-best solution. Using ‘big data’ opens up possibilities for measuring wellbeing, but researchers should use them cautiously and in conjunction with traditional surveys, where possible.

Further reading

Atamanov, Aziz, Sharad Alan Tandon, Gladys Lopez-Acevedo and Mexico Alberto Vergara Bahena (2020) ‘Measuring Monetary Poverty in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: Data Gaps and Different Options to Address Them’, Policy Research working paper no. WPS 9259, World Bank Group.