In a nutshell

The consequences of a lack of data transparency could not be more pressing than during this pandemic.

Phone surveys are an important step to feed decision-makers with critical information during the Covid crisis.

But more needs to be done: by releasing the data that have already been collected, governments can demonstrate their readiness to do what it takes to keep citizens safe and protect them from undue economic harm.

With Covid-19, decision-makers face the unenviable task of making a trade-off between saving people’s lives and protecting their livelihoods. The situation is rapidly evolving, with case numbers increasing and policies being updated regularly. The impacts of this pandemic are severe, with its effects particularly felt by the poor and vulnerable.

Effective policy-making is challenging at the best of times. With Covid, it takes on a different dimension. To do the best possible, decision-makers need timely and relevant information.

While there is an urgent need for data to assess the impact of the crisis, new data collection based on face-to-face survey interviews is hindered by social distancing protocols and mobility restrictions. Phone surveys, on the other hand, do not require face-to-face interactions. Such surveys can be deployed rapidly, repeated regularly and adapted swiftly to changing circumstances.

Phone surveys are not a panacea for every situation as they have limitations, including under-coverage of groups with poor network connections or with limited access to phones. Still, on balance, they constitute a valuable tool and certainly during the kind of emergency we are currently experiencing.

The World Bank has experience with phone surveys: the first initiatives to use them for welfare monitoring date back to 2011. To date, phone surveys have been used in many different circumstances, including in response to emergencies. They were successfully rolled out during the Ebola crisis to monitor the impact of extreme climate events and in conflict and fragile situations – including to track the welfare of displaced people.

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have realised the value of phone surveys to respond to Covid-related data needs. As of 3 May, most are at different stages of planning and implementation of phone surveys. These surveys are often planned with a monthly periodicity for an initially foreseen duration of three to six months.

Many surveys are being prepared by cooperation between the World Bank and national statistics offices. This makes it possible not only to respond to government demand but also ensures that capacity for emergency monitoring using phone surveys remains available in the future.

While data from these surveys are critical to inform decision-making, and while it is impressive how the region has embraced this innovative tool, other data remain equally essential. Unfortunately, existing practices of non-release or limited release continue unabated.

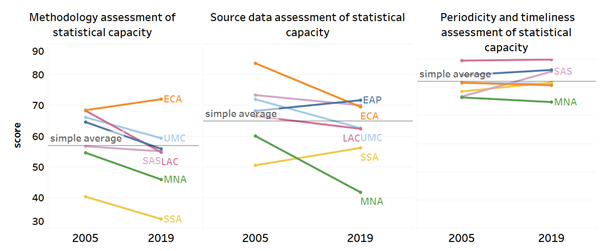

Data have been collected often at significant taxpayer expense, but remain unavailable. It is not uncommon for finance ministers not to have access to data, paid for with Treasury resources for which they are responsible. How bad the situation is, can be seen in Figure 1 from a recent World Bank study.

Not only is the MENA region (excluding high-income countries) below the global average in all three key dimensions of statistical capacity, the region is closer to the much poorer Africa region than to comparators in Eastern Europe or Asia. Tellingly, in all key dimensions of statistical capacity (methodology, source data, and data periodicity and timeliness), an already unsatisfactory situation has worsened over the past 15 years.

Figure 1:

Source: World Bank, Bulletin Board on Statistical Capacity, accessed in WDI on 1 May 2020.

Note: Regional aggregates exclude high-income countries. ECA stands for Europe and Central Asia; EAP stands for East Asia and Pacific; SAS stands for South Asia; LAC stands for Latin America and the Caribbean; UMC stands for upper-middle income; SSA stands for sub-Saharan Africa.

A recent World Bank report (Arezki et al, 2020) argues that lack of data access and transparency hurts the region and limits its economic growth prospects.

The consequences of a lack of data transparency could not be more pressing than during this pandemic: as statistical agencies continue not to release microdata that could potentially save people’s livelihoods and even their lives, politicians are forced to make decisions based on anecdotes, gut feeling and intuition.

There is an easy way out of this: allow analysts and researchers to use existing data for the greater public good. Release the micro data that is sitting idle on computers in statistical offices. Almost all countries in the region possess surveys that could be released at the touch of a button. This is one Covid measure that costs nothing and that could make a big difference.

Phone surveys are an important step to feed decision-makers with critical information during this Covid crisis. But more needs to be done. By releasing the data that have already been collected, governments can demonstrate their readiness to do what it takes to keep citizens safe and protect them from undue economic harm. Doing the right thing was never cheaper and more cost-effective.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.