In a nutshell

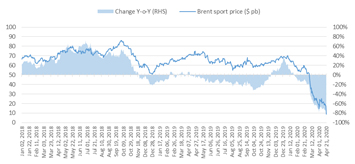

The rapid deterioration of the global economic outlook and the breakdown of the OPEC+ have weighed heavily on oil prices, which have fallen by around 70% in the year to date to the lowest figure in over 20 years.

Underperformance of the oil sector is expected to spill over to non-hydrocarbon activities in the United Arab Emirates and more generally in the Gulf Cooperation Council, generating further pressures on the government budget and external current account, especially if the oil price shock exhibits further persistence.

Risks are compounded by the adverse implications of Covid-19 for the economy; but ample international reserves, the strongly capitalised and liquid banking sector, and large buffers in the sovereign wealth funds are reassuring for the UAE to come out of the crisis stronger and with a more diversified economy.

Crude prices plummeted in April of this year on the expectation that the coronavirus outbreak will cause a deep global recession. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) went into negative territory in April for the first time in history, due to the lack of storage facilities, and very low demand dragged down the Brent Crude oil price to below $16 per barrel.

The negative prices of WTI sparked concerns about the depth of the crisis that has hit the oil sector after lockdowns have been imposed in many of the world’s major economies. The plunge in oil prices has come despite the OPEC+ deal to cut almost 10% of global crude supply (or about 10 million barrels per day, bpd) effective May 2020, bringing supply down to approximately 90 million bpd.

Meanwhile, the latest reports show that demand for oil, due to the pandemic, would fall by 30%, equivalent to an estimate of 70 million bpd. Subsequently, data published by the Energy International Agency showed that US crude inventories rose by 15 million barrels weekly, to 518.6 million barrels, reflecting constraints on the inventory capacity. Furthermore, China has a total of 1,300 million barrels in commercial and strategic crude inventory. At this level, the country will struggle to maintain current oil import levels without exceeding storage capacity.

Figure 1: Oil prices in the global market (Brent)

Source: International Energy Agency

Oil price implications for economic activity in the United Arab Emirates

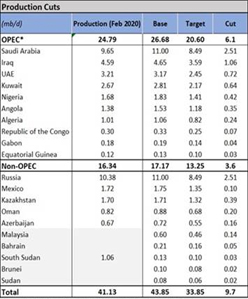

In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected a contraction of growth in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries of 2.7% in 2020. Non-oil activity is expected to be a major drag on the near-term outlook, contracting by negative 4.3% this year, a significant downward revision from the 2.3% growth projected in the October World Economic Outlook. The agreed cut in production by OPEC+ (see Table 1) and the significantly lower oil prices would also have a negative impact on the UAE economy. This is likely to compound the adverse implications of the Covid-19 crisis for the UAE economy.

Table 1: Impact of the April OPEC+ agreement on country oil production

Source: IMF

The UAE has the most diversified economy in the GCC region, registering the highest share of non-oil GDP compared to the total – 70.2% in 2019, . As data are not available for all countries for 2019, comparing 2018 non-oil GDP in the total GDP is estimated at 74% for the UAE. For Saudi Arabia, this share is 66%, while for Qatar, Kuwait and Oman, it is 53%, 68% and 63%, respectively.

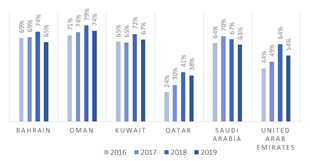

Notwithstanding the increased diversification of the UAE economy, the oil price shocks are transmitted to the economy through the high dependency of government revenues and spending on oil exports.

Figure 2: Share of hydrocarbon revenues (% of total government revenues)

Source: IMF. Numbers reported for Kuwait correspond to fiscal years.

Insulating the UAE economy from the effects of the oil price shock will hinge on domestic policies, refraining from a pro-cyclical fiscal stance by decreasing spending to accommodate the decline in oil revenues. Countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies could counter the effects of the lower oil prices on the non-oil economy.

Indeed, in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, the Central Bank of the UAE has taken measures adding up to $70 billion, 18% of GDP, in two phases, through a Targeted Economic Support Scheme (TESS). The measures are designed with the objectives of facilitating the provision of temporary relief by banks to all affected private sector corporates, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and individuals; facilitating additional lending capacity by banks, through the relief of existing capital and liquidity buffers; and outlining expectations and actions to be taken under TESS by all banks and finance companies operating in the UAE.

The TESS consists mainly of $13.6 billion capital buffer relief, $13.6 billion zero cost funding support, $26 billion liquidity buffer relief and $16.6 billion reduction of regulatory cash reserve requirements. In addition, macro-prudential measures have been announced to provide added support, targeting important segments of the economy, such as SMEs, real estate, etc.

On the fiscal front, the Federal and Emirates’ authorities have announced measures adding up to $7.5 billion to stimulate the economy. Specifically, $4.5 billion has been made available by the federal government. In addition, $3 billion worth of measures were announced by local governments. The collective measures and fiscal interventions targeted relief to SMEs, households and government-related entities.

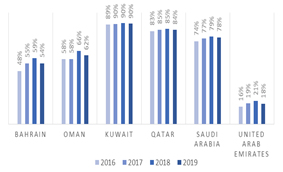

Regarding the external sector, as Figure 3 shows, the UAE economy is the most diversified in terms of exports in the GCC – only 18% of total exports were hydrocarbon products in 2019. But using data for the first half of 2019, 29% of the UAE’s non-oil exports and 24% of its re-exports are to the GCC. If we include the other two countries from the Middle East region that are heavily dependent on oil exports – Iraq and Iran – the non-oil exports and re-exports represent 34% and 37% of the UAE’s total exports, respectively.

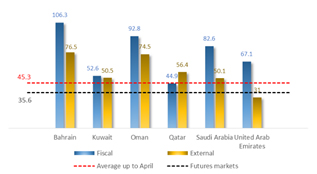

The combined effects of the decline in the oil price and the decline in demand in major importing countries could be significant for UAE non-oil exports and re-exports. But the international reserves position at the Central Bank of the UAE should not be at risk as the external current account breakeven price stands at around $31 (see Figure 4), below the projected oil price for 2020 at $35.6 (IMF and crude oil futures).

As of the end of March 2020, UAE international reserves stood at $107.3 billion. They represent 5.3 months of imports and 94.9% for the currency cover – that is, relative to the monetary base, well above the 70% cover, as per the law of the Central Bank of the UAE.

Figure 3: Share of hydrocarbon exports (% of total exports)

Source: IMF

Figure 4: Fiscal and external current account breakeven prices

Source IMF Regional Economic Outlook (April 2020)

External risks include financial flows. The global slowdown generated a deterioration of risk sentiment, which could reduce capital flows to the country, especially portfolio flows, as many emerging countries have experienced recently. Combined with the squeeze on domestic revenues and liquidity, the risk-off strategy that many emerging economies have experienced could stem investment inflows and further adversely affect equity prices.

For example, the two major stock indexes – ADX and DFM – realised a drop of 23.8% and 31.6% in March 2020, respectively, while year-to-March 2020, the drop was 26.4% and 35.9%, respectively. More recently, markets have recovered, building on the optimism and strong fundamentals of the economy and the stimulus support provided by the public sector.

Oil price implications for government spending and the budget deficit

The IMF projects oil prices at $35.6 in 2020; but the estimated fiscal breakeven for the UAE stands at $67.1. This would lead to a severe deterioration of the government’s fiscal space.

But banks in the UAE remain well capitalised with ample liquidity with Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), Tier 1 Capital, Common Equity Tier 1 and Eligible Liquid Assets Ratio standing at 16.9%, 15.8%, 13.9% and 17.3%, respectively, well above the minimum regulatory requirements. Moreover, sovereign general government debt in the UAE remains low, at 20% of GDP in 2019 and sovereign ratings are strong (Aa2 from Moody’s), providing options to raise debt in the international market.

Diversifying options of financing the fiscal deficit will help to address priorities for near-term spending to stimulate the economy without raising serious risks for fiscal sustainability – especially in a scenario of short-lasting low oil prices.

Consistent with economic priorities, the Emirates and Federal governments are demonstrating a countercyclical fiscal stance to counter the consequences of Covid-19. The announced stimulus packages, together with the decrease in oil related revenues, will increase the fiscal deficit. Depending on the duration of the lower oil prices and the constraints on production, financing needs are likely to increase and so will the need for borrowing.

In the case of a short-term oil price shock, no major correction would be required to maintain the pace of priority spending and the government can capitalise on the good ratings and low debt burden to diversity sources of financing.

But if the oil price shock reveals further persistence over the medium term, fiscal reforms should prioritise spending to maximise the return on growth, plus support for private sector activity and mobilisation of non-oil revenues to ensure fiscal sustainability.

The timing, however, would be crucial to strike the right balance between fiscal sustainability and recovery of non-energy growth. The ultimate goal is to sustain the momentum of further diversification of the economy to reduce oil dependency and hedge against continued fluctuations with oil price volatility and spillovers from the global economy.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as those of the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates.