In a nutshell

The lack of data transparency and measurement inconsistencies in labour market statistics pose an important challenge to policy-making as they can distort the role of women in MENA societies.

Using precise definitions of labour force participation, the evidence suggests that low female labour force participation in MENA might be a generational issue.

Female labour force participation rates in Egypt almost double when women who are engaged in non-market economic activities are counted as employed.

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) lag behind many other parts of the world in terms of their capacity to generate data. Advanced economies, for example, have modern data collection systems, generating publicly available data that is accessible to the research community, the media and civil society.

In our recent report (Arezki et al, 2020), we explore data gaps in labour market outcomes across MENA countries. We bring particular attention to issues of mismeasurement and definitions of labour market outcomes.

Measuring unemployment in MENA

Most advanced economies rely on the International Labour Organization (ILO) definitions of employment and unemployment rates, which are considered to be the gold standard. The unemployment rate computed as the share of unemployed individuals divided by the total labour force (unemployed and employed individuals) requires the definition of employment, unemployment and the target working-age population.

According to the ILO, the working-age population is restricted to those aged between 15 and 64 years old; an individual is considered to be unemployed if he or she is without work, available for work and seeking work; while an individual is considered to be employed if he or she is engaged in paid employment or self-employment.

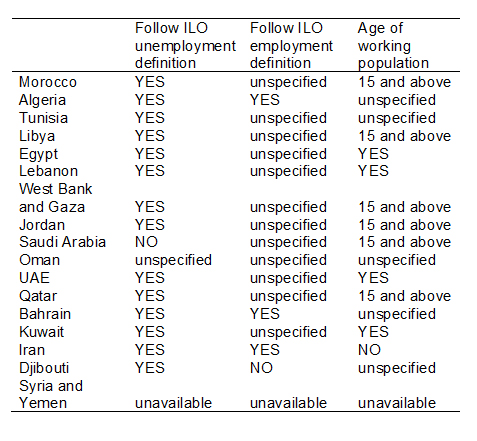

Relying on information from national statistics websites across MENA countries, we report in Table 1 the inconsistencies between the ILO definition and the definitions employed in MENA economies. Indeed, we find that most MENA countries do not follow the ILO definitions for employment, unemployment and the working-age population. Moreover, in many cases, MENA countries do not report the definitions they use.

Table 1: Consistency of employment and unemployment across MENA

Source: Authors’ summary based on information from national statistics websites.

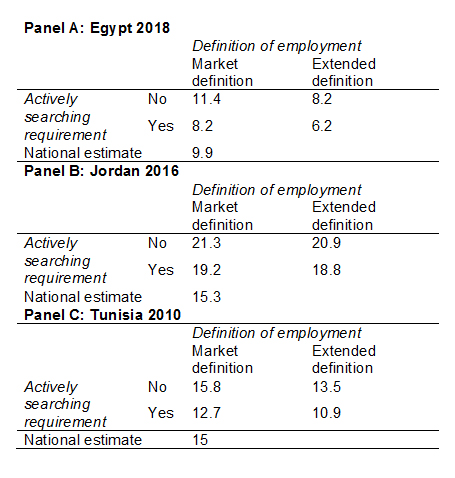

We use data from the Labour Market Panel Surveys across three MENA countries – Egypt (in 2018), Jordan (in 2016) and Tunisia (in 2014) – to compute total unemployment rates following various definitions and national unemployment rates collected from national statistics agencies.

The difference between the market and extended definition in Table 2 is that the former considers only individuals who are employed in market economic activities to be employed while the latter additionally considers those who engage in non-market economic activities as employed.

As Table 2 shows, the unemployment rates computed using the Labour Market Panel Surveys vary widely depending on the definition employed. Moreover, none of the estimated unemployment rates coincides with the national estimates collected from statistics agencies across Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia.

Table 2: Estimated versus official total unemployment rates

Source: Labour Market Panel Surveys (ERF), national statistical agencies (CAPMAS in Egypt and INS in Tunisia) and ILOSTAT.

Female labour force participation: a generational issue?

The measurement of female labour force participation in MENA is another issue that brings attention to the importance of precise definitions and transparency.

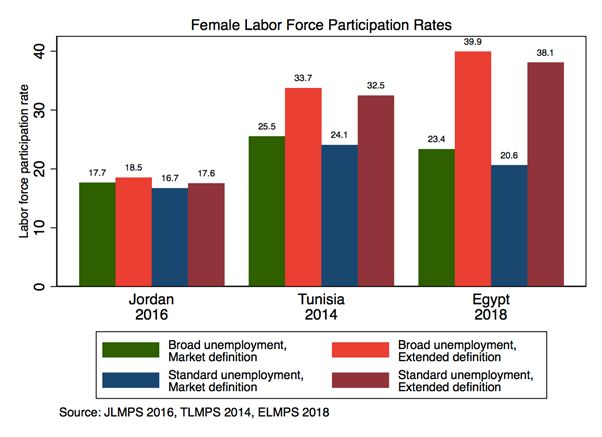

Figure 1 shows how female labour force participation rates vary drastically according to the definition employed. We make a distinction between market and non-market economic activities, and also between broad unemployment (active job search is not required for the individual to be considered to be unemployed) and standard unemployment (active job search is required for the individual to be considered to be unemployed).

Figure 1 shows large discrepancies depending on the definition that we employ. Importantly, it highlights the importance of non-market or subsistence economic activities for women in MENA. In fact, female labour force participation rates in Egypt almost double when we consider women who are engaged in non-market economic activities as employed.

Figure 1: Female labour force participation rates

We observe similar patterns in Tunisia where female labour force participation rates are drastically higher when using the extended definition of employment compared with the market definition. Indeed, the ILO definition of employment incorporates both those engaged in paid employment and those who engage in self-employment as employed.

These measurement issues highlight the importance of definitions and data transparency as mismeasurement of female labour force participation rates can distort the role of women in MENA societies.

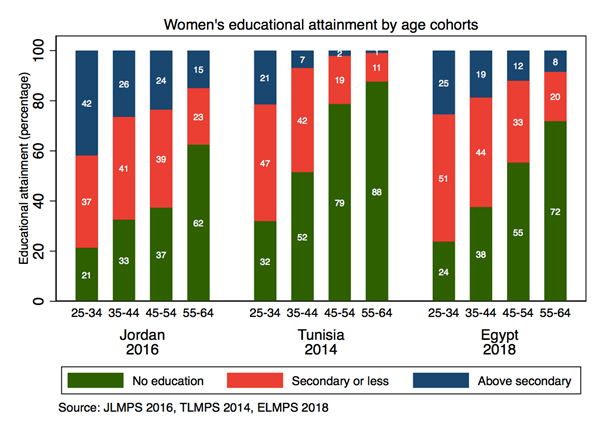

In recent decades, women in MENA have become increasingly educated. Figure 2 presents the share of women with no educational degree, with secondary education or less, and with above secondary by age cohorts. This figure shows that a large proportion of young women have high levels of educational attainment: secondary education or less; and above secondary education. On the other hand, older women have a greater incidence of being uneducated across the three countries: Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia.

Figure 2: Women’s educational attainment in MENA

We investigate whether the low female labour force participation rates observed in MENA are a generational issue. We find that the observed gap in female labour force participation rates between younger and older cohorts can be attributed to educational differences rather than family formation or the number of children within a household. Our estimates suggest that the explained part of the outcome differential is almost entirely due to differences in educational attainment.

Overall, our report brings attention to the importance of data transparency and accuracy for the measurement of labour market outcomes across MENA. Without precise definitions, it is impossible to replicate any of the official labour market statistics using independent data sources. Precise definitions are also particularly relevant for assessing women’s engagement in the labour market and the role of women in MENA societies.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.