In a nutshell

In 2019, 11 MENA countries seemed to be on unsustainable fiscal paths: their reported primary fiscal balances were insufficient to stabilise their gross debt-to-GDP ratios.

Fiscal sustainability assessments are hampered by lack of data transparency about stocks of public debt.

In the time of Covid-19, transparency about current debt stock and future flows of debt – as well as the uses of funding – are critically important for debt assessments and debt negotiations.

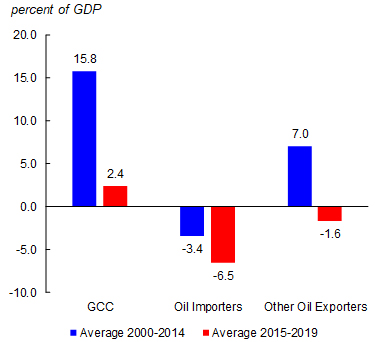

Many countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have been facing macroeconomic fragility even before the Covid-19 crisis. Figure 1 shows that the weighted average current account balances of MENA countries have declined across the board between 2000-2014 and 2015-2019.

Figure 1: The decline of MENA’s current account balances

In our recent report (Arezki et al, 2020), we systematically analyse the current account sustainability of MENA countries using an econometric model that determines how a country’s current account balance is related to fundamental determinants such as demography, expected changes in economic growth, GDP per working-age population and exposure to commodity price fluctuations.

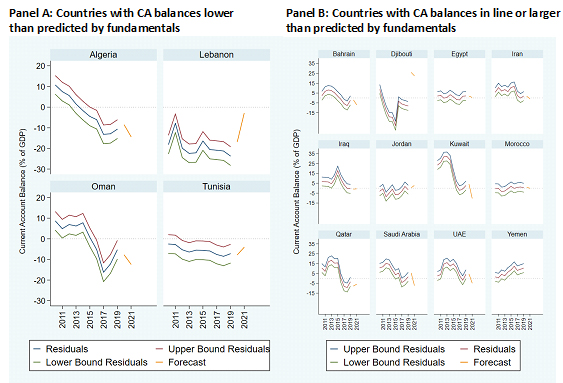

Four MENA economies have current account balances significantly lower than what is predicted by country fundamentals. These unexplained current accounts are the residuals of the model – that is, the difference between the predicted value and the observed value.

Figure 2 represents the 95% confidence interval of the residuals and the forecast residuals. Panel A consists of countries where the reported current account balances are statistically significantly lower than what is predicted by the model: Algeria, Lebanon, Oman and Tunisia. Panel B consists of those whose current account balances are not statistically significantly lower than the model’s predictions.

Figure 2: Unexplained current account (CA) balances for MENA countries

Source: World Bank Staff’s calculation

To assess fiscal sustainability, we employ three commonly used approaches:

- Approach 1: Construct required primary fiscal balance (that stabilises the public debt-to-GDP ratio) and compare it to the observed balance (Arezki et al, 2020; Debrun et al, 2019).

- Approach 2: Construct the structural fiscal balance by removing the components of revenues and expenditures that are automatically connected to the business cycle (Arezki et al, 2020; IMF, 2011). It is arguably more precise to assess solely the structural fiscal balance because it captures the fundamental fiscal condition of a country.

- Approach 3: Estimate a relationship between the primary fiscal balance and public debt in the previous period across a global sample of countries, following Mendoza and Ostry (2008).

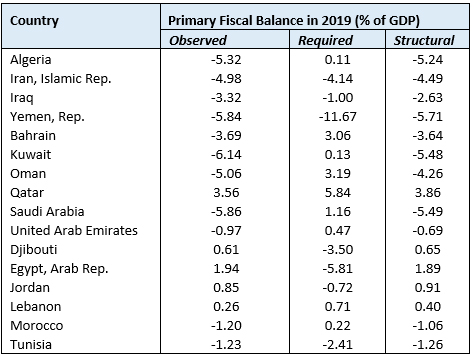

Table 1: Primary and structural fiscal balances versus debt-stabilising primary fiscal balances in MENA in 2019

Source: Arezki et al (2020)

Table 1 presents the structural and required primary balances for 2019. Fiscal sustainability worsened relative to 2018-11: 16 MENA countries in our sample had a required primary balance that was larger than their observed primary balance.

Table 1 requires some qualifications related to debt data transparency:

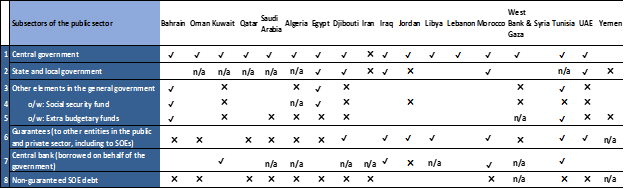

- First, gross public debt is not reported consistently across MENA countries. As Table 2 shows, MENA countries do not report many components of public debt. Macroeconomic data issues in MENA hinder efforts to understand the region’s macroeconomic fragility.

- Second, Table 1 shows the required primary balance for 2019 when data on debt, interest rates and growth are all realised. Estimating the expected future required primary balances, while more meaningful for policy discussions, is more challenging and subject to greater uncertainty.

- Third, even for countries where the required fiscal balance is smaller than the observed balance, the finding should be treated with cautious optimism. Current sustainability does not guarantee future sustainability. Interest rates, growth rates and exchange rates could change and complicate fiscal sustainability.

Table 2: Debt reporting in MENA countries

Source: Arezki et al (2020). Note: Table II.2 follows the public debt reporting template of World Bank-IMF’s Debt Sustainability Framework (see IMF, 2017).✔ indicates the country reports the type of debt (for both domestic and external debts); × indicates the country has the type of debt but does not report it; n/a = not applicable and indicates that the country might not have this type of debt; blank cells indicate that World Bank economists do not have information regarding whether the country has the type of debt but does not report it, or that the country does not have the type of debt, or that the debt might be included in total government debt. Debt reporting is as of 2019.

In the third approach, fiscal balance sustainability is assessed by estimating the relationship between the primary fiscal balance and debt-to-GDP ratios in previous years. Following Mendoza and Ostry (2008), when the partial correlation between the primary fiscal balance and the previous year’s debt-to-GDP ratio is positive, the fiscal path is interpreted as being ‘sustainable’.

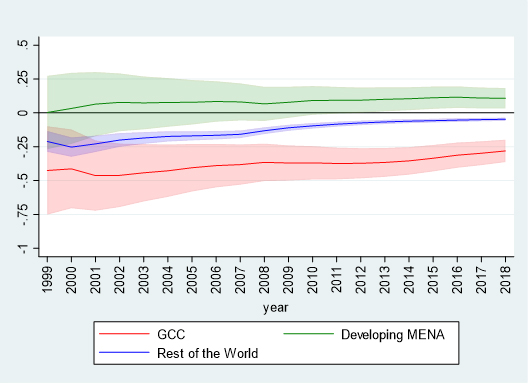

Our report (Arezki et al, 2020) presents the analytical framework in detail and contrasts MENA – including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and developing countries in the region – with the rest of the world.

For the rest of the world, the primary balance has a negative and statistically significant relationship with lagged debt on average; this suggests that when lagged debt increases, the primary balance deteriorates. This is clearly not a sign of fiscal sustainability. The primary balance for the GCC countries has an even more negative relationship with lagged debt than the rest of the world (see Figure 3).

The good news is that the primary balance for developing MENA countries has a positive relationship with lagged debt, a sign that their situation might be fiscally sustainable.

Finally, it cannot be overstated that the findings on MENA’s debt sustainability should be interpreted with caution given the incomplete reporting of debt data. The results might change when more complete data become available.

As with lack of data during a pandemic, obfuscation of debt information hampers open policy debates in search of solutions. In the time of Covid-19, more transparency about current debt stock and future flows of debt (as well as the uses of funding) are critically important for debt assessments and debt negotiations.

Figure 3: The relationship between primary fiscal balances and past debt – MENA and the rest of the world since 1990

Note: The vertical axis of the figure shows recursive estimates of econometric regressions between primary and lagged debt with other controls (please see Appendix C3 for details). The estimating windows are gradually expanded. For example, the point estimate for 1999 is the result of the estimation with the sample from 1990 until 1999. Similarly, the point estimate for 2018 is the result of the estimation with the sample from 1990 until 2018. But the changes over time in the estimated coefficients are the result of the inclusion of data from the last year in the sample. The bands indicate 10 percent confidence intervals.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Debrun, Xavier, Jonathan Ostry, Tim Willems and Charles Wyplosz (2019) ‘Public Debt Sustainability’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 14010.

International Monetary Fund (2011) ‘When and How to Adjust Beyond the Business Cycle? A Guide to Structural Fiscal Balances’, Technical Notes and Manuals, IMF Fiscal Affairs Department.

Mendoza, Enrique, and Jonathan Ostry (2008) ‘International evidence on fiscal solvency: Is fiscal policy “responsible”?’ Journal of Monetary Economics 55(6): 1081-93.