In a nutshell

Lebanon urgently needs external liquidity support targeted directly to the banking system in order to restore depositor confidence and to unfreeze the economy; in parallel, debt should be reset gradually on a sustainable path.

This response borrows from the resolution of the global financial crisis ten years ago by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

Any policy response that falls short of restoring both growth and liquidity will be futile, necessitating ever-larger external assistance and repeated recapitalisations.

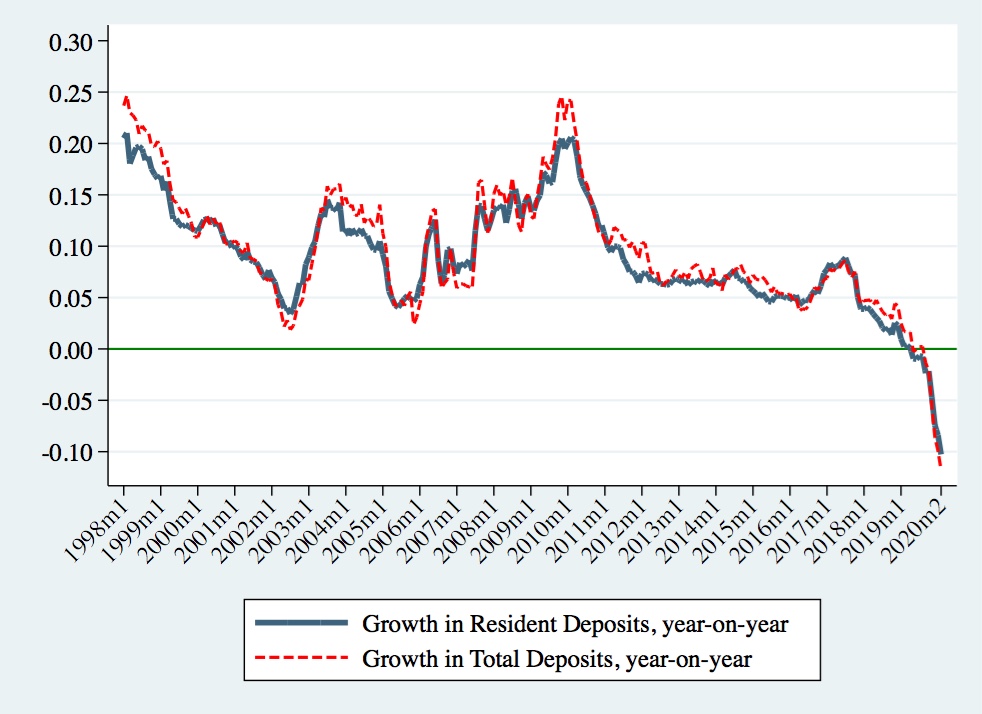

Lebanon’s financial crisis developed over a long period of time before shaping into a dollar liquidity shortage from the summer of 2019. For many years, a dedicated base of investors supported most of the country’s funding needs, channelled through the banking system. These investors were depositors – residents placing their savings and remittances, as well as expatriates and regional depositors – all contributing to consistently positive net deposit inflows over many years (as Figure 1 shows).

Deposit inflows financed persistent budget and trade deficits. For example, budget deficits averaged minus 11.1% for the period 1999-2019, which cumulated into a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 150% by 2019. Similarly, trade deficits were reflected in a worsening current account deficit of minus 22.6% for 2008-18 compared with minus 15.1% for 1999-2007.

Figure 1: Commercial bank deposit growth (1998-2020)

Note: The monthly series are year-on-year percent change and are computed from the Banque du Liban reported data for the consolidated balance sheets of commercial banks (Post and Pre IFRS9).

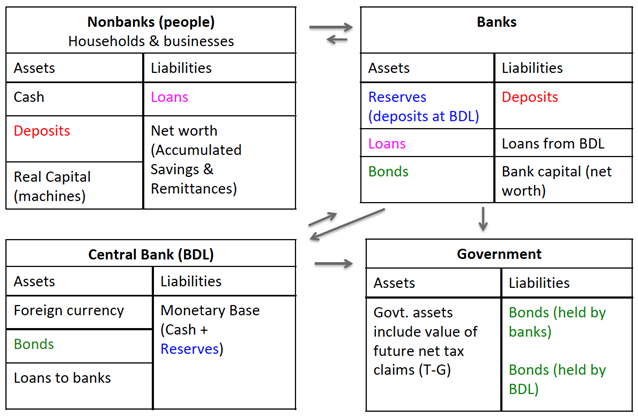

People withdrew their deposits en masse in 2019, reflecting their loss of confidence in the banking system. This ‘sudden stop’ triggered the crisis and exposed the fragile underlying funding scheme: one in which the balance sheets of all four sectors of the domestic economy – the private sector; the banking system; the central bank; and the government – are closely interconnected (see Figure 2).

Any event can trigger a crisis if the balance sheets are vulnerable enough as they became in Lebanon from a build-up of overextended and mismatched balance sheets – with respect to both maturity and currency.

For example, the private sector has large claims on the domestic commercial banks in the form of deposits: 327% of output by 2019. Commercial banks have direct claims on the government (12% of bank assets by 2019) that are dwarfed by indirect exposure via their deposit claims on the central bank (58% of assets).

This means that while banks have tried to decrease their government debt over time, the banking system as a whole (banks and the central bank) still holds the majority of government debt. As a result, central bank assets reached 240% of output by 2019, up from 63% in 1999. All of bank deposits, central bank assets and government debt place Lebanon in the top 95th world percentiles when scaled by GDP.

Figure 2: The claims and cross-claims in the Lebanese economy

As famously summarised by Dornbusch (2001), a crisis ‘takes longer than you think but then happens faster than you would have thought.’ Without any policy backstop, a downward spiral develops.

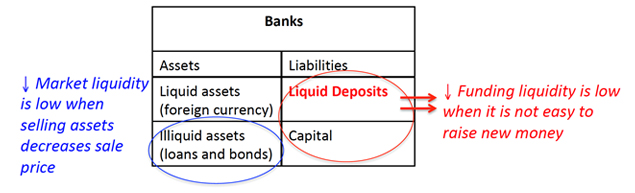

Figure 3 shows how banks combine short-term demandable debt (deposits) with long-term less liquid assets (bonds and loans). This illiquidity is common to every financial crisis because no bank holds liquid cash equal to its deposits (see Bernanke, 2013).

On top of that, foreign liquid assets fall short of demandable debt in dollars (the majority of Lebanese deposits). When depositors demand liquidity at the same time, even solvent banks will have problems meeting demand. Banks drain foreign liquid assets such as those held with correspondent banks, but that is not enough.

For example, foreign liquid assets had already declined from 8.4% of Lebanese bank assets at the start of 2017 to 5.6% by 2019:Q3 and have declined by more than 25% since then (based on the latest data available for February 2020).

At the same time, banks curb new loans and call in loans early to get cash, causing second-round adverse feedbacks to the private sector and more liquidations. The government, in trying to reduce its debt burden by defaulting, also pushes banks deeper into insolvency. Any write-off on bank assets such as government bonds first hits bank capital, and when that is not enough, hits deposits too.

In short, the ‘leave-it-alone’ liquidationist approach – the Great Depression option – spirals down with a two-way feedback between increasing bankruptcies and illiquidity. Lebanese banks have imposed ad hoc capital controls to limit outflows, but this is a stopgap at best and does nothing to restore depositor confidence, which is critical to getting out of a crisis and arresting a free-falling currency.

Figure 3. Liquidity Shocks to Banks

I propose that a key first step in any effective policy response is to separate the government debt problem from the liquidity problem. This way, debt restructuring can proceed without causing more liquidity problems.

Lebanon urgently needs external liquidity support targeted directly to the banking system in order to restore depositor confidence and to unfreeze the economy. In parallel, debt should be reset gradually on a sustainable path.

This response borrows from the resolution of the global financial crisis ten years ago by the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB). These central banks provided liquidity to maintain the flow of credit despite their banks being exposed to the collapse in housing prices or to losses from the European periphery’s sovereign debt, which took longer to address.

In the Lebanese case, external liquidity would substitute for the role of the central bank as a lender-of-last-resort because the Banque du Liban cannot print dollars. Like other central banks in dollarised countries with fixed exchange rates, the Banque has tried to maintain high foreign currency reserves. But its capacity has diminished over time as it shifted to financing the government debt (for example, foreign currency gross reserves as a share of Banque du Liban assets were only 21.6% by 2019:Q3, down from 62.3% two decades earlier in 1999:Q3).

If the Banque du Liban were to use its dollar reserves, they are not enough to cover deposits. If it were to provide liras to banks to sell for dollars in the market, this adds to depreciation pressure. A similar dollar shortage problem was faced by the ECB and other central banks in 2008 (and again today with the coronavirus crisis), leading the Fed to set up vital swap lines with foreign central banks. This can be adapted to the Lebanese case with bilateral/multilateral support (see Mora, 2020, for details).

I will conclude by addressing two common and related misconceptions. First, debt restructuring alone will not restore liquidity and can make it worse. Nor will liquidity provision alone work. Both are needed. Liquidity is a ‘flow’ that can appear rapidly or disappear altogether rather than being reallocated elsewhere as a lump ‘stock’ of funds (see Adrian and Shin, 2009).

This explains why the speech by ECB president Mario Draghi in 2012 promising to do ‘whatever-it-takes’ to save the euro and the financial system suddenly restored confidence and liquidity in the European periphery while previous attempts failed. For example, borrowing costs (interest rate spreads above Germany) immediately decreased by 300-500 basis points for Italy and Spain after the speech and not because these countries had suddenly reduced their debt-to-GDP ratios. For example, the Italian debt-to-GDP ratio was and remains high, above 130% (Blanchard, 2017).

In a similar way, arranging swap or credit lines can transform the illiquid balance sheets of the Banque du Liban and banks to the dollar liquidity needed. The point is not to settle all accounts and close business. Simply having a large enough line (not necessarily using it all) shifts the equilibrium from a bad self-fulfilling one where everyone wants immediate cash to a normal equilibrium. It is myopic to focus on how the existing debt loss burden is to be distributed while ignoring future liquidity implications.

Second, successful attempts to re-establish debt sustainability have mostly occurred through output growth and primary surpluses, causing debt-to-GDP ratios to go down steadily. For example, both the UK and New Zealand emerged from the Second World War with debt-to-GDP ratios above 150% and took 30 years to get below 50% (Blanchard, 2017).

In the case of the European sovereign debt crisis, countries like Greece and Italy have stabilised their debt-to-GDP ratios at high levels while only Ireland has decreased its ratio because of healthy growth. Ireland managed to reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio from 120% in 2013 to less than 60% by 2019 because of an average annual growth rate of 9.9% during this period compared with 1.6% growth in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. For example, while Greece’s debt ratio decreased by 20 percentage points at the time of its debt restructuring in 2012, it worsened the next year to 180% due to the collapse in economic activity and has remained elevated (Gourinchas et al, 2017).

It makes sense for Lebanon to restructure its debt to move away from bad debt dynamics and lower its borrowing costs, but debt dynamics can worsen as rapid austerity risks lower growth. One key empirical finding is that the failure of fiscal adjustment plans is largely driven by deviations of economic growth from initial projections (see Mauro and Villafuerte, 2013).

In addition, too deep a haircut in an economy where the debt is domestically held is self-defeating. This would cause losses to pension and savings funds, bank failures and more illiquidity with depositors running for the exits. Therefore, any policy response that falls short of restoring both growth and liquidity will be futile, necessitating ever-larger external assistance and repeated recapitalisations.

Further reading

Adrian, T, and HS Shin (2009) ‘The Shadow Banking System: Implications for Financial Regulation’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 382.

Bernanke, BS (2013) The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis, Princeton University Press.

Blanchard, O (2017) Macroeconomics: Global Edition, Pearson.

Dornbusch, R (2001) ‘A Primer on Emerging Market Crises’, National Bureau of Economic Research No. 8326.

Gourinchas, PO, T Philippon and D Vayanos (2017) ‘The Analytics of the Greek Crisis’, National Bureau of Economic Research Macroeconomics Annual 31(1), 1-81.

Mauro, P, and M Villafuerte (2013) ‘Past Fiscal Adjustments: Lessons from Failures and Successes’, IMF Economic Review 61(2): 379-404.

Mora, N (2020) ‘A Primer on the Financial Crisis in Lebanon: A Historical and Cross-Country Perspective’.