In a nutshell

The impact of the pandemic on the Arab region’s inflows of foreign direct investment will be immense: estimated total losses of between $7.1 and $17.2 billion.

The projected FDI falls will have effects across the economy, choking off financing, business expertise, market access and other factors needed to help the region develop.

Temporary controls on capital flight could be a means to stem harmful and severe investment outflows, while also ensuring long-term returns for the investors.

The Covid-19 outbreak is first and foremost a human tragedy, affecting millions of people’s health and wellbeing. It is also a new potential source of volatility, a threat to the resilience and economic stability of Arab countries, and a further burder on those countries already suffering from macroeconomic deterioration.

While it is still too early to understand fully its impact on global value manufacturing and supply chains, and how it will affect employment, productivity and incomes in our region, what we know so far is that Covid-19 is spreading at an accelerated rate and has caused significant disruptions to global value chains (GVC), particularly in the world’s leading economies.

These countries have responded with unprecedented public health and economic responses, mandating business closures and introducing stimulus packages on a scale previously thought impossible.

The situation is rapidly evolving. At the time of writing, there have been more than two million confirmed cases of Covid-19 reported by 210 countries and almost 150,000 deaths from the virus. The scenarios for the pandemic are evolving day-by-day in response to the quick spread.

The global top 5,000 multinational enterprises (MNEs) have significantly revised their 2020 earnings downwards. We are witnessing the greatest decline in FDI capital expenditure (capex) since the global recession in 2008, and a potentially substantial decline in the cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) portion of FDI. UNCTAD (the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) projects a drop in global FDI of between 30% and 40% leading up to 2021.

Here, we attempt to evaluate the likely impact of Covid-19 on FDI into the Arab region, focusing on ‘greenfield investments’, a category of FDI in which direct investors typically establish new enterprises in the host country. Greenfield investment involves the provision of fresh capital as opposed to reflecting a transfer in ownership of existing assets – M&A.

We harness information on greenfield FDI projects assembled from a unique database developed by fDi Intelligence, which monitors cross-border investments in new projects and expansions of existing ventures, covering all sectors and countries worldwide since 2003.

The major advantage of this data source compared with UNCTAD statistics is the availability of a sectoral classification for each investment project. It contains up-to-date and reliable information on countries of origin and destination, and provides other relevant information, such as investment date, capex, jobs created, sector and business activity undertaken by the foreign affiliate.

Covid-19 impacts on investment

Arab countries have significant links to the main countries affected by Covid-19 in general and the EU, the US and China in particular; economic relations between Arab countries and the three major economic blocs have skyrocketed in recent decades, particularly through trade and FDI. Merchandise trade – exports and imports – with the 16 most affected countries (the US, Italy, Spain, China, Germany, France, Iran, the UK, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Turkey, South Korea, Austria, Canada and Portugal) increased from $191 billion in 2001 to $60 billion in 2018.

Since 2008, 34% of Arab exports of oil and not-oil products have bee destined for the EU (15.7%), China (12.7%) and the US (5.6%), compared with 45% of imports originating from these blocs: 25.9% from the EU, 14% from China and 4.8% from the US.

For oil products, the picture is different. In 2018, 36.4% of Arab exports of oil were absorbed by the EU (16.4%), China (13.8%) and the US (7%). With the recent increase in US production of natural gas, the third client of oil and gas for the Arab region is now ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) with 10.8% of total Arab exports of oil and gas.

In 2018, the 16 most affected countries invested almost $39 billion (in 522 FDI projects) in the Arab region, amounting to almost half (47%) of total capex in the region. The US, France and China together accounted for about a third (29.5%) of total capex in 2018 ($82.7 billion).

Globally

Many attempts have been made to estimate initial magnitudes of the impacts of Covid-19 on FDI. An initial assessment by UNCTAD (8 March 2020) shows that the impacts are not so much global as they concentrated in economies that were severely hit by the disease. But the second assessment published on 27 March takes account of the global expansion of the pandemic, which is now affecting nearly every country on earth.

The initial projections underestimated impacts on global FDI compared with those of the post-pandemic period during which many countries, both developed and developing, were forced to impose drastic measures to mitigate the expansion of the virus, causing devastating effects on their economies. Measures include travel limits, lockdown and border closures, causing disturbances in an interconnected world, thus affecting FDI flows as a result of global demand shocks, supply chain disruptions as well as lower capex and lower profits of the top MNEs.

The longer the virus shuts down economic activity in the most afflicted countries, the longer the indirect ripple effects through the rest of the world will be felt, in addition to the direct effects of further countries falling victim to Covid-19. The longer that global shutdowns persist and demand remains suppressed, the harder it will be to turn the global economy ‘back on’ and resume activities after the crisis.

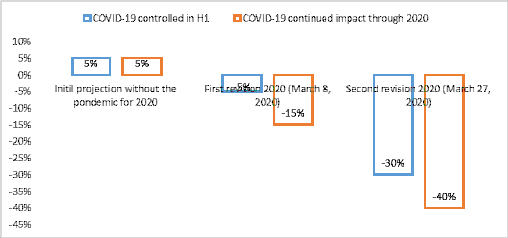

Depending on whether the virus continues through 2020 or is controlled in Q1, the revised UNCTAD projections show a decrease in FDI inflows of between 30% and 40% – that is, a 25 percentage points difference between the initial projections (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Projections of impacts of Covid-19 on global FDI

Source: UNCTAD (2020)

Negative demand shocks and interruptions in both production and supply chains were especially felt in economies that are closely integrated in GVCs centred around China, the Republic of Korea, Japan and Southeast Asian economies, causing negative impacts on all three major FDI types (market-seeking, efficiency-seeking and natural resource-seeking). The spread of the epicentre of the virus to the EU and the US has similarly dampened demand along supply chains leading into their markets.

The projected decline in earnings of the global 5,000 MNEs would also have an indirect impact on FDI. Indeed, any decrease in their earnings would lead to a reduction in retained earnings and therefore to a decrease in reinvested earnings, which represent 52% of global FDI. This has been witnessed in investors pulling out of projects financed in developing countries to shore up their losses.

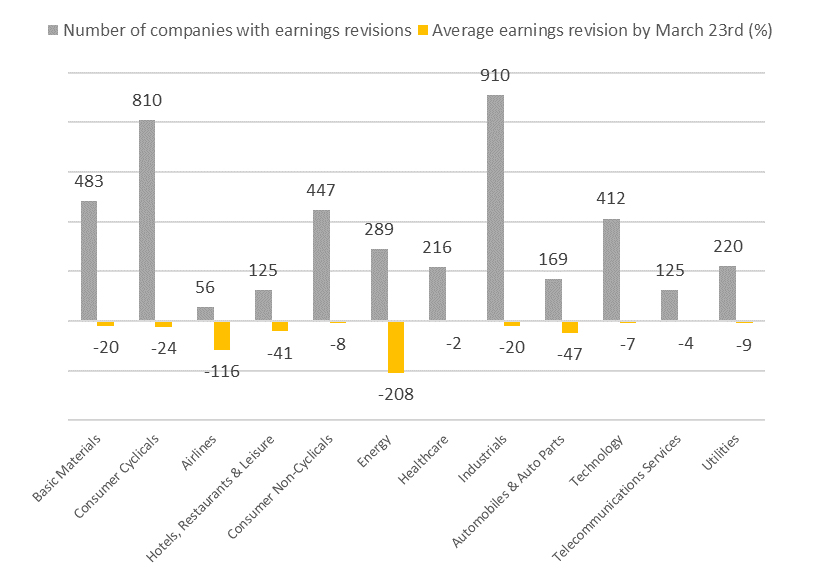

While all industries are likely to be affected, some will be hit particularly hard. For example, energy and basic material industries, airlines and the automotive industry are expected to suffer the most, with FDI falling by 208%, 116% and 47% respectively. The outlook for hydrocarbons is particularly precarious due to the unprecedented fall in global demand and supply-affecting actions taken by major oil producers.

The Arab region

UNCTAD data show that FDI inflows in the Arab region totalled around $30.8 billion in 2018. Figure 2 shows that the top five Arab FDI recipients absorbed the overwhelming majority of total inflows to the region in 2018 (92%), compared with 84% in 2017.

Figure 2: Total FDI inflows composition of the Arab region, 2018

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from UNCTAD, 2020

Until today and as far as we know, no plausible estimates have been made for the Arab region on the likely impacts of Covid-19 on FDI inflows. At the same time, an unprecedented number of macroeconomic assessments are being published on a daily basis describing detailed impacts on economic and social performance both at the global and country level.

Despite the relevance of these economic assessments, they omit the important role of FDI as one of the three drivers of economic growth, in addition to domestic demand and exports. Indeed, the potential macroeconomic effects of the crisis as outlined in existing studies would be far worsened if they accounted for the drying up and even reversing of FDI flows.

Performing more plausible assessments based on up-to-date and detailed knowledge of the channels of impacts by country is an important step in understanding the impacts and designing the mitigation or stimulus impacts. Concrete evaluations of the expected changes in exports, consumption and investment (including FDI) are a prior condition to evaluating aggregate effects on GDP.

The situation is more problematic in the Arab region, where many countries are highly dependent on the world oil market, which is the sector most affected by the pandemic and ensuing economic climate.

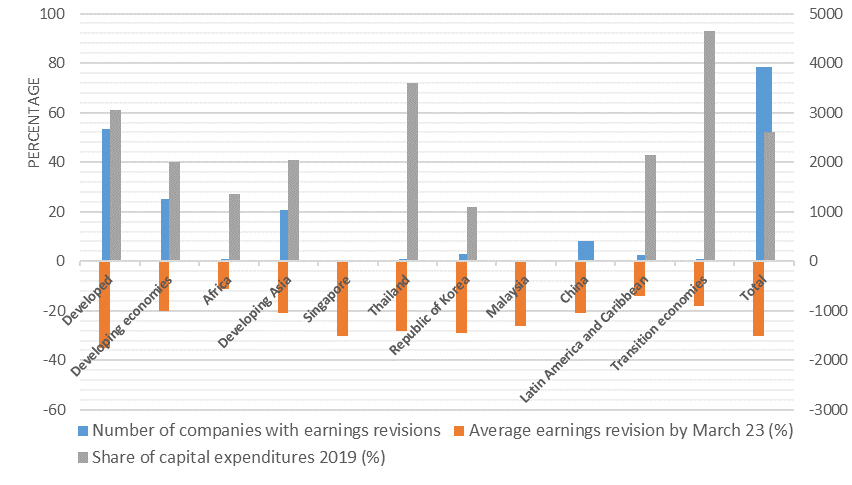

To fill this assessment gap, we performed an original assessment for the Arab region based on the latest available information on the earnings revisions and capex of the top 5,000 MNEs by region and sector (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Earnings revisions and capital expenditures of the top 5,000 MNEs, by region

Source: UNCTAD, based on data from Refinitiv SA

Note: The Arab region is not individually disaggregated in the UNCTAD’s assessments

Figure 4: Earnings revisions and capital expenditures of the top 5,000 MNEs, by sector

Source: UNCTAD, based on data from Refinitiv SA.

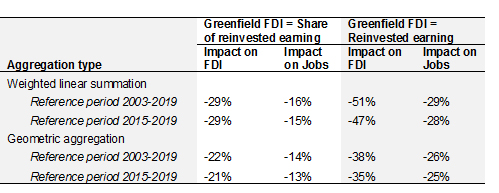

Two alternative assumptions have been adopted in the calculations about the share of earnings invested. The first assumes that only a share of the earnings is invested while the second assumes that all earnings are invested. Under both cases, it has been also assumed that FDI inflows in the Arab region will be mechanically affected by the reduced level of earnings. In other terms, all new foreign capital investment will be exclusively funded from the earnings.

Moreover, two alternative periods have been considered as a benchmark for the calculations: 2003-19 and 2015-19. Finally, the level of earnings revisions of the top 5,000 MNEs have been estimated under two alternative aggregation approaches (additive and geometric) of sectoral and regional average earnings revisions as shown in Figures 3 and 4. The results of the estimation are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Downward projected pressure on FDI and jobs in the Arab region

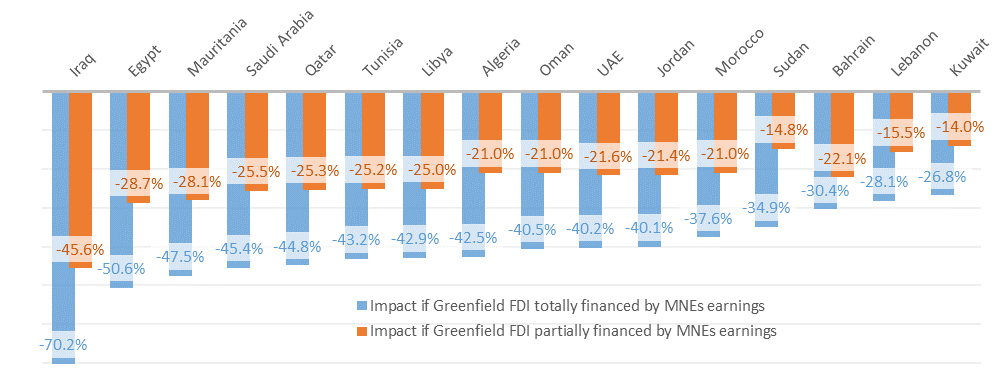

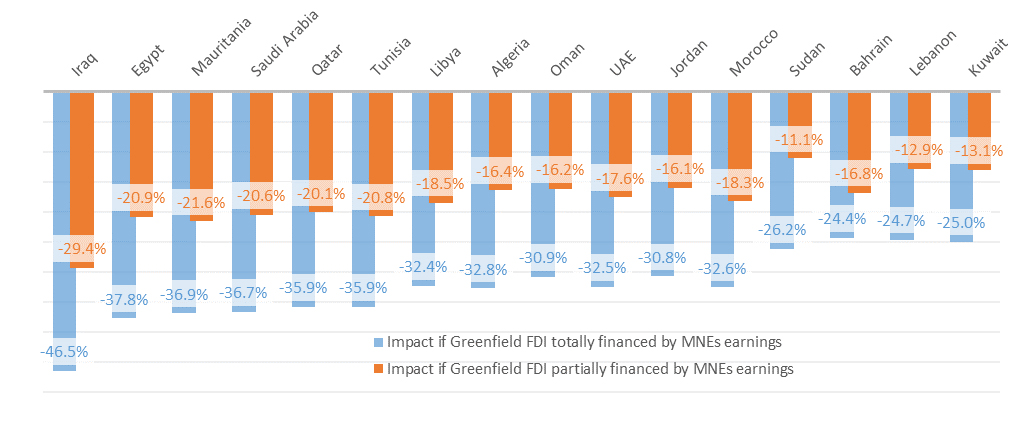

The results show that if only a portion of earnings are invested based on the previous trends, FDI inflows in the Arab region are expected to drop by between 21% and 29% in 2020 compared with projections. In addition, the losses for job creation will vary between 13% and 16% compared with a situation without the pandemic.

In the case where all earnings will be invested, the impacts are much more pronounced and the Arab region will face a serious problem in terms of financing investment, creating jobs and even achieving external payments balance. In fact, under this hypothesis, FDI inflows will drop at least 33% but may reach 51%.

The most affected country is Iraq followed by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Mauritania and Tunisia. Kuwait and Lebanon are expected to be less affected (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Impact of Covid-19 on greenfield FDI in the Arab countries (weighted linear summation)

Source: authors’ calculations using the global database on greenfield database

Figure 6: Impact of Covid-19 on greenfield FDI in the Arab countries (geometric aggregation)

Source: authors’ calculations using the global database on greenfield database

What next?

The impact of the pandemic on the region’s FDI inflows will be immense. The estimated total losses of FDI inflows for the Arab region will be between $7.1 and $17.2 billion.

Regardless of which sectors suffer more in relative terms, a drop in investment of that scale will be economically and socially costly for many Arab economies, both through direct and indirect effects.

Meanwhile, the sectoral distribution of the loss in FDI inflows is uneven in terms of size. Manufacturing and mining are likely to be hit particularly hard, followed by construction and education. These have severe implications, given the job creation by each sector and type of investment.

Based on these new estimates at country and sectoral level, economy-wide assessments of the impacts of the reduction in FDI inflows in the region will be carried out in a second stage, which represents a major improvement compared with the previous ex ante assessments of the economic impacts of Covid-19.

The findings of this exercise call for the importance of mainstreaming investment policies in general and those for foreign investors in particular in all stimulus programmes for economy recovery currently in progress.

Indeed, the projected FDI falls will have effects across the economy, choking off financing, business expertise, market access and other factors that are needed to help the region grow and develop.

Furthermore, temporary controls on capital flight similar to those employed successfully in Malaysia during the 1997-98 financial crisis can be explored as a means to stem harmful and severe investment outflows, while also ensuring long-term returns for the investors.

The views expressed are those of its authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations or DHAMAN. The authors extend special thanks to John Sloan (associate economic affairs officer, UNESCWA) for his inputs and comments, and to Nancy Daccache for her research assistance.