In a nutshell

Growth of productive capacity – which accounts for both demographics and the value added from production – provides a more sensible measure of the economic potential of a nation than GDP per capita: given their high working-age populations, MENA countries need to recognise the importance of this more accurate measurement.

Countries with a larger working-age share of population than their peers – such as Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain – should in theory have higher economic potential.

Likewise, if countries have access to mineral resources, they may appear wealthy in national accounts, but that gives little indication of the productivity of the rest of the economy.

We hear so much bad news every day that we should stop and celebrate some good news: global prosperity has been rising since 2007 and reached its highest level in 2019.

The 2019 Legatum Prosperity IndexTM, published in November 2019, reveals that 148 out of 167 countries are experiencing higher levels of prosperity than a decade ago. This includes an improvement in 12 of the 19 nations of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Nations are truly prosperous when they have Inclusive Societies, Open Economies and Empowered People, which are the domains into which our Prosperity Index is structured. Underneath these domains, we measure the strengths and weaknesses of nations’ performances across 65 policy-focused elements. Each of these elements has been constructed to have both a theoretical and a tangible relationship with social wellbeing, which is proxied using Cantril’s Ladder, and economic wellbeing.

When assessing economic wellbeing, our aim is to measure the true value created by nations and communities. In this way, the strength of the underlying structures of production can be assessed, rather than emphasising the income accrued and the rates of consumption. Another way of considering this would be to ask what is the underlying capacity of an economy, given those who could be contributing to its success.

One reason for generating such a measure is to benchmark the performances of countries on the pillars of the Open Economies domain – the part of the Index that encompasses measures of trade access, business regulations, the availability of finance and other such metrics of economic openness. We would expect there to be a high (but not exact) correlation between a singular measure of economic wellbeing and the domain scores.

As a welfare measure, GDP per capita acts as a useful metric for the average income of the population of a nation. But while it can also be seen as a satisfactory first-order approximation of value creation, it is widely considered to be incomplete for many purposes.

This is especially true for countries with atypical population structures and for those with extra income generated from natural resources – known as resource rents. For example, if a country has a larger working-age share of population than its peers, its economic potential should theoretically be higher. Likewise, if it has access to mineral resources, it may appear wealthy in national accounts, but that gives little indication of the productivity of the rest of the economy.

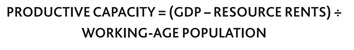

In our endeavour to compare our measure of holistic prosperity with a more singular measure of economic success, we have accounted for both demographics and the value added from production in a new metric: productive capacity.

This is an especially important concept for MENA, where atypical demographic structures and high resource rents are particularly prevalent. This means that many of the countries in the region see a substantial difference between their GDP per capita and productive capacity.

We focus here on why accounting for population structures matters for measuring economic wellbeing and people’s lived experiences.

Countries with a low dependency ratio – that is to say, with relatively high proportions of people of working age – would normally be expected to produce more per capita than countries with a higher dependency ratio. The impacts of dependency ratios are not simply on how national accounts report; they are intrinsically linked to people’s lived experiences.

Fundamentally, a higher dependency ratio means that there are fewer economically active people contributing tax. Those not of working age generally require higher government spending (in the form of education and healthcare spending, as well as state pensions), so a higher dependency ratio requires this to be provided to more people with fewer resources.

Although the great majority of countries have working-age populations comprising between 60% and 70% of the total, there is a large disparity between the highest working-age percentage (85%, in Qatar) and the lowest (47%, in Niger). Most developed economies have working-age populations above 60%. Japan is well known for having a very ageing population, with the highest proportion of people over the age of 65 (over 25%), yet still 61% of their overall population is working age.

There are only a few countries in the world with working-age populations higher than 70%, and a disproportionate number of those are found in MENA – with Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain exhibiting the highest proportions in the world. It is therefore vital that countries in the region recognise the importance of accurately measuring the underlying capacity for production by accounting for the working-age population.

One could argue that we could go further than using the working-age population as a denominator in calculating productive capacity and use just those in employment – in effect, a measure of labour productivity.

Although doing this would be a valid and useful measure, as it captures the current capabilities of a workforce, it would fail to capture the economic wellbeing of all members of society. From the point of view of national policy, it is far more useful also to consider those who are excluded from the labour market or who do not participate fully for family or other reasons, because their wellbeing is equally important.

In accounting for the latent income derived from resource rents and the proportion of the population who would be feasibly expected to work, growth of productive capacity provides a more sensible measure of the economic potential of a nation than GDP per capita. It measures the trends of the fundamental aspects of the economy and ensures that our Index reflects the underlying economic potential and overall prosperity of each country, not just income statistics.