In a nutshell

In comparison with Iraq, Libya and Yemen, the Syrian economy is in a much worse situation in terms of physical destruction – along with vanished human capital and destroyed institutions.

Programmes for repatriation of refugees from the Arab conflicts should focus on systematic and large-scale economic reconstruction plans, which should naturally embed institutional upgrading.

Post-conflict trauma experienced by refugees and superior economic opportunities offered in host countries may make refugees – especially the high-skilled ones – less willing to return.

Following the Arab uprisings, many countries in the Middle East and North Africa experienced conflict, which resulted in extensive destruction along several dimensions. Millions of people have been forced to leave their homes. Physical, financial and human capital resources have fled to safety.

The 2019 Euromed report (FEMISE-ERF, 2019) includes discussion of the economic cost of conflict, as well as post-conflict reconstruction scenarios in the four main afflicted countries: Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen. The intensity of violence has declined significantly and political problems have changed nature in these countries recently.

But conflict is not over yet and a massive return of physical and human capital is still a remote possibility in the short term. Nevertheless, policy-makers should start discussing alternative scenarios for repatriation and economic reconstruction in conflict-afflicted countries with the ultimate purpose of streamlining transition and normalisation.

In recent work (Ceylan and Tumen, 2018, 2019), we generate satellite-based night-light data series using GIS (Geographic Information System) methods to measure the economic cost of conflict in the afflicted countries. This approach has two major advantages:

- First, night-light intensity is a good alternative measure of income growth at national level and thus, it can be a complementary source of information in calculating national income.

- Second, economic and policy analyses of local economic activity are hindered by the lack of reliable data at the regional level. The night-light data are available at a far greater degree of geographical fineness than is attainable by standard income and product accounts (Henderson et al, 2012). Therefore, the GIS methods provide a robust basis for measurement and analysis of economic activity at the regional level.

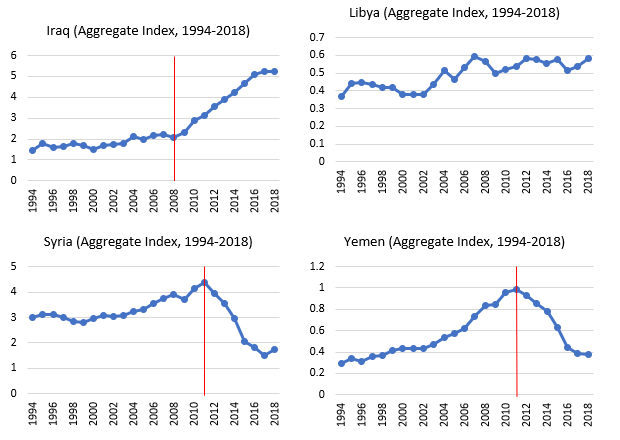

Figure 1: Satellite-based estimates for the economic cost of conflict in Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen. Source: Ceylan and Tumen (2018, 2019).

Figure 1 provides a visual characterisation of the aggregate-level estimates for the afflicted countries. The data period is 1994-2018, with some breaks in 2014 and 2018 for some regions.

It should be noted that the timing and duration of conflict differ across those four countries – so country-specific stories differ based on the nature of the conflict that each country has experienced. But the findings consistently suggest that there is a significant negative association between conflict and macroeconomic performance.

Another observation is that in comparison with Iraq, Libya and Yemen, the Syrian economy is in a much worse situation in terms of physical destruction – along with vanished human capital and destroyed institutions. Repatriation programmes should focus on systematic and large-scale economic reconstruction plans, which should naturally embed institutional upgrading.

In addition to direct estimates, a more theory-consistent approach is also needed to incorporate realistic counterfactual exercises and analyse post-conflict scenarios. Devadas et al (2019) offer such an approach. Specifically, they use the long-term growth model of Devadas and Pennings (2019) to perform after-war simulations based on three counterfactual exercises featuring different settlement scenarios for Syria.

The first is a moderate (baseline) scenario incorporating the ‘Sochi plan’. Second, an optimistic scenario is constructed based on long-term political settlement. And, finally, a pessimistic scenario is formed featuring fragmented political power.

These three scenarios also accompany three different levels of reconstruction assistance and repatriation volumes. The optimistic scenario features a large amount of reconstruction assistance and repatriation, while both are lower in the pessimistic scenario. The no-conflict scenario assumes trivial reconstruction assistance and repatriation volumes.

The findings suggest that high post-conflict economic performance is possible in Syria if long-term political stability is achieved; market-friendly mechanisms are redesigned to target efficient allocation of resources throughout the economy; appropriately designed reconstruction and repatriation programmes are implemented; and those programmes are supported by sustainable financing facilities.

Repatriation policies and efforts should also account for the main findings of the Euromed report. The evidence suggests that refugees are less likely to leave their host countries than economic migrants; they have stronger incentives to invest in their own and children’s human capital in the host country; and they have a lower propensity to accumulate savings and send their money back home as remittances – so their potential contribution in terms of reconstruction after conflict may also be limited.

These behavioural patterns should be considered in designing repatriation programmes, as post-conflict trauma experienced by refugees and superior economic opportunities offered in host countries may make refugees – especially the high-skilled ones – less willing to return.

On the other hand, experience suggests that most of the repatriation efforts have been less successful than expected due to various problems including:

- lack of understanding of the cultural, religious and historical context;

- lack of coordination between governments and NGOs;

- lack of anticipation of the recurrence of conflict in the post-repatriation period;

- failing to address the issues of past property and land ownership;

- and lack of appropriately designed micro-credit assistance, housing support and employment subsidy programmes, which research shows to be extremely useful.

These lessons should be accounted for in designing repatriation programmes for the refugees in the future.

Finally, the refugees are now in the process of integrating into the socio-economic life in their host countries. Developed countries have been implementing financial and technical support programmes to facilitate the integration process.

For example, Turkey has been implementing large-scale EU-funded programmes to integrate Syrian children into the Turkish public education system. The overall enrolment rate is above 60% and the enrolment rate is expected to increase further in the near future.

Host countries are now discussing how to provide official work permits and even to provide selective citizenship to Syrian refugees. As the resolution of conflict is delayed, those integration efforts will proceed further and the refugees may become less likely to participate in voluntary repatriation plans. International cooperation is needed to end the conflict in afflicted countries and rapidly to implement well-designed repatriation programmes to expedite economic reconstruction.

Further reading

Ceylan, ES, and S Tumen (2018) ‘Measuring economic destruction in Syria from outer space’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal, 19 June.

Ceylan, ES, and S Tumen (2019) ‘Estimating the cost of conflict in the MENA region with satellite data: Evidence from Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen’, unpublished manuscript, TED University.

Devadas, S, IA Elbadawi and NV Loayza (2019) ‘Growth after war in Syria’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8967.

Devadas, S, and SM Pennings (2019) ‘Assessing the effect of public capital on growth: An extension of the World Bank Long-Term Growth Model’, Journal of Infrastructure, Policy, and Development 3: 22-55.

FEMISE-ERF (2019) ‘Repatriation of Refugees from Arab Conflicts: Conditions, Costs and Scenarios for Reconstruction’, Euromed report.

Henderson JV, A Storeygard and DN Weil (2012) ‘Measuring economic growth from outer space’, American Economic Review 102: 994-1028.