In a nutshell

Labour force participation rates in Egypt declined from 51% in 2012 to 48% in 2018.

Employment rates declined from 47% to 44% over the period from 2012 to 2018.

Standard unemployment rates remained stable, but ‘discouraged unemployment’, those who want to work but have given up searching for jobs, increased in 2018.

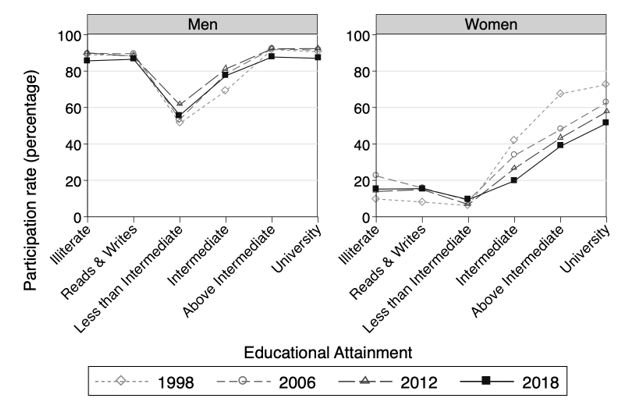

Labour force participation has decreased for both men and women in Egypt. The decrease in men’s participation is a new development, but women’s declining participation has been a long-term trend (Krafft et al, 2019a). Despite rising educational attainment, which usually yields increased female labour force participation (Assaad et al, 2018), educated women’s participation continues to fall.

Labour force participation has two components: employment and unemployment. Decreases in employment rates are driving declining labour force participation in Egypt. A large share of young men and women are ‘not in education, employment or training’ or ‘NEET’ (Amer and Atallah, 2019). Unemployment rates remained stable, although discouraged unemployment, those who want to work but have given up searching for jobs, increased (Krafft et al, 2019a).

The declines in labour force participation mean that the potential contributions of a large share of Egypt’s increasingly educated population are untapped. Creating a conducive business environment that can generate good jobs is critically important to engaging all of Egypt’s human potential.

Labour force participation has fallen, especially for educated women

Despite decreases in demographic pressures, labour force participation rates in Egypt have fallen. Labour force participation was at a high of 52% in 2006, fell to 51% in 2012, and dropped further to 48% in 2018, according to the new Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) (Krafft et al, 2019a).

Women’s participation declined from 27% in 2006 to 23% in 2012 and 21% in 2018. We would expect that as Egyptian women become more educated, their labour force participation would similarly increase.

This is not happening in Egypt, in part due to the decline of the public sector (women’s preferred employer), the low quality of jobs created by the private sector and the difficulties women face reconciling domestic responsibilities with work (Assaad et al, 2018; Assaad et al, 2019; Assaad et al, 2017; Barsoum, 2015; Selwaness and Krafft, 2018).

A new development, as of 2018, is that men’s participation has decreased as well, falling from 80% in 2012 to 76% in 2018 (Krafft et al, 2019a). This trend has been corroborated by Egypt’s labour force surveys (LFSs) (Krafft et al, 2019b). Participation declined slightly for men of all education levels (Figure 1).

Educated women’s participation has steadily fallen, while less educated women have continued to participate at low rates. For example, women with an intermediate education participated at rates above 40% in 1998, but by 2018, only 20% of this (increasingly large) group participated.

Figure 1: Participation has steadily declined for educated women, and recently for all men

Labour force participation rate (percentage), standard market definition, by education, sex and wave, ages 15-64

Source: Krafft, Assaad, and Keo (2019) based on data from ELMPS 1998-2018

Employment rates have fallen, especially for youth

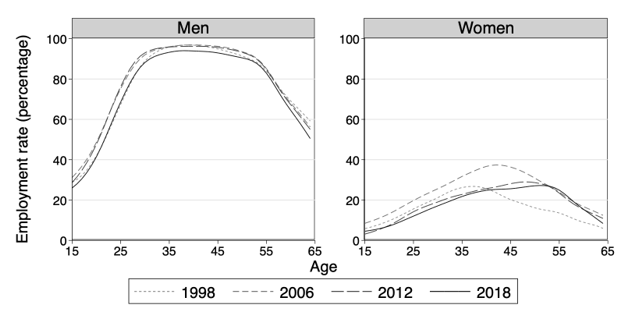

Labour force participation has two components: employment and unemployment. The decline in participation in Egypt has been driven by a decrease in employment. Employment rates declined from 47% to 44% overall (Krafft et al, 2019a). Women’s employment was as high as 22% in 2006, but declined to 18% in 2012 and 17% in 2018. Men’s employment peaked at 77% in 2012 but fell to 72% in 2018.

The declines in employment occurred especially for youth and to some extent at prime working ages for men (Figure 2). For women, employment declined for youth through age 55.

The low rates of employment of youth and increasingly educated women are particularly concerning as under-use of Egypt’s human resources. A large share of young people are NEET (Amer and Atallah, 2019). The share of women aged 25-29 who are NEET has risen from 76% in 2006 to 82% in 2018, while the share of young men who are NEET rose in all age groups from 15-29, from 7.2% to 8.9%.

Figure 2. Employment rates fell and are particularly low for young women

Employment rate (percentage), market definition, by sex, age and wave, ages 15-64

Source: Krafft, Assaad, and Keo (2019) based on data from ELMPS 1998-2018

Standard measures of unemployment are stable, but discouraged unemployment increased

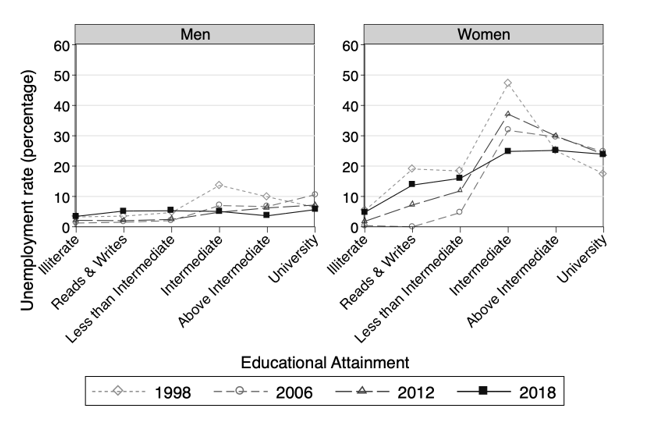

Unemployment in 2018 (8.2%) was similar to 2012 (8.7%) (Krafft et al, 2019a). Unemployment increased slightly for men: from 4.2% in 2012 to 4.9% in 2018. It fell for women: from 23.7% to 19.5% between 2012 and 2018. The LFSs captured additional rising and then falling unemployment in the interim between 2012 and 2018 (Krafft et al, 2019b).

At over 20%, unemployment rates remained highest for educated women (Figure 3). Comparing 2018 with 2012, unemployment rates fell for educated men but rose for less educated (and younger) men. Unemployment rates for women were stable for university graduates, fell for above intermediate and intermediate graduates, and rose for less educated women. Unemployment also continued to extend into older ages for women, as fewer young women worked.

Figure 3: Unemployment rates have fallen for the educated and risen for the less educated

Unemployment rate (percentage), standard market definition, by highest education, sex and wave, ages 15-64

Source: Krafft, Assaad, and Keo (2019) based on data from ELMPS 1998-2018

Although the standard unemployment rate was fairly stable, the broad unemployment rate, which includes the discouraged, rose: from 9.6% to 11.1% between 2012 and 2018. The increase occurred both for men (from 4.7% to 5.8%) and women (from 25.8% to 27.8%). The rise in broad unemployment suggests that Egyptians are increasingly discouraged about their job opportunities. While they would like to work, they have given up searching in light of the lack of available jobs.

Making use of Egypt’s human potential

Egypt must address longstanding structural challenges for the labour market to make use of its human resources. Despite reduced demographic pressures, labour force participation and employment have fallen. Unemployment has remained steady, but discouraged unemployment has risen. These are all signs of a weak, labour-absorbing paradigm on the demand side of the labour market (Assaad et al, 2018).

To make full use of its human potential, Egypt must create good jobs that will attract its increasingly educated youth. Private sector jobs that can be reconciled with women’s domestic responsibilities are crucial, since marriage and its domestic responsibilities are a major constraint on women’s participation.

Either the private sector must have greater flexibility or domestic responsibilities must be reduced. Time-saving technologies and a greater role for men in the home are both solutions to the latter, while job-sharing and home-based employment show potential to address the former constraint (Krafft and Assaad, 2015).

The business environment for the economy as a whole, and competition particularly, play an important role in job creation (Assaad et al, 2018; Krafft and Assaad, 2015).

Further reading

Amer, Mona, and Marian Atallah (2019) ‘The School to Work Transition and Youth Economic Vulnerability in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Assaad, Ragui, Abdelaziz AlSharawy and Colette Salemi (2019) ‘Is The Egyptian Economy Creating Good Jobs? Job Creation and Economic Vulnerability from 1998 to 2018’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Assaad, Ragui, Rana Hendy, Moundir Lassasi and Shaimaa Yassin (2018) ‘Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation’, IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 11385.

Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft and Irene Selwaness (2017) ‘The Impact of Marriage on Women’s Employment in the Middle East and North Africa’, ERF Working Paper No. 1086.

Assaad, Ragui, Shaimaa Yassin and Caroline Krafft (2018) ‘Job Creation or Labor Absorption? An Analysis of Private Sector Job Growth by Industry in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 1237.

Barsoum, Ghada (2015) ‘Young People’s Job Aspirations in Egypt and the Continued Preference for a Government Job’, in The Egyptian Labor Market in an Era of Revolution edited by Ragui Assaad and Caroline Krafft, Oxford University Press.

Krafft, Caroline, and Ragui Assaad (2015) ‘Promoting Successful Transitions to Employment for Egyptian Youth’, ERF Policy Perspective No. 15.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Caitlyn Keo (2019a) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt from 1988-2018: A Gendered Analysis’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Khandker Wahedur Rahman (2019b) ‘Introducing the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey 2018’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Selwaness, Irene, and Caroline Krafft (2018) ‘The Dynamics of Family Formation and Women’s Work: What Facilitates and Hinders Female Employment in the Middle East and North Africa?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1192.