In a nutshell

Since the 1950s, the urban population in Turkey has increased dramatically due to massive rural-to-urban migration and a high fertility rate.

In 2017, 75% of the Turkish population lived in cities, making it a very highly urbanised country, but there are substantial spatial inequalities between regions on almost every metric, including productivity.

Doubling the employment density in an area increases average wages by 3.8-4.2%; having access to other markets is the most important determinant of the productivity differences in Turkey.

In the past decade, empirical research on agglomeration economies has provided robust evidence on the productivity gains associated with larger cities. Yet despite extensive evidence on these gains in developed countries, little is known about the impact of urbanisation in the rest of the world.

Addressing the knowledge gap on urban economies in the developing world is important for two reasons. First, the majority of the world’s urban population lives in countries that are far poorer than the advanced countries from where the evidence mainly comes (Glaeser and Henderson, 2017). In addition to the importance of urban areas being the drivers of economic growth in those countries, they also concern the lives of millions of people who reside and work in these places.

Second, the models and stylised facts documented for developed countries may not apply entirely to developing countries, as the characteristics and roles of cities may differ (Chauvin et al, 2017). For example, the rapid urbanisation observed in developing countries in the second half of the past century may have generated different benefits and costs compared with the Western world where the urbanisation rate has been relatively stable.

In recent work (Özgüzel, 2019), I provide evidence on urbanised economies in the non-Western world by focusing on Turkey, an upper-middle-income developing country that has experienced fast urbanisation and a high rate of growth of the urban population.

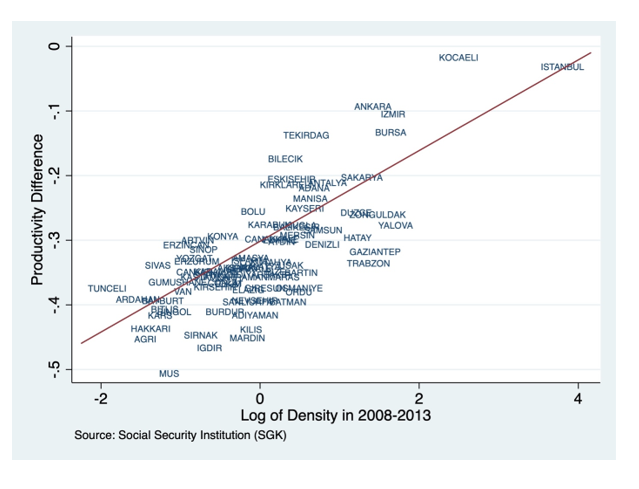

Since the 1950s, the urban population in Turkey has increased dramatically due to massive rural-to-urban migration and a high fertility rate. In 2017, 75% of the Turkish population lived in cities, making it a very highly urbanised country. But there are substantial spatial inequalities between regions on almost every metric (income, production, life quality, etc.), including productivity.

Spatial differences in productivity occur due to differences in the skill composition of the workforce, local non-human endowments and interactions between workers or between firms (Combes and Gobillon, 2015). Understanding differences in productivity requires consideration of all these explanations.

Simultaneously addressing all of these factors makes it possible to assess the importance of each element in the productivity differences. Quantifying these magnitudes is especially crucial for the formulation of policy to address inequalities.

I analyse social security records, a new administrative dataset that has only recently become available to researchers and thus has never been used in research before. I address the endogeneity bias due to reverse causality by using historical instruments based on census data from the Ottoman Empire and the early years of the Turkish Republic.

I find the elasticity of wages with respect to employment density in provinces to be 0.056-0.06. This means that doubling the employment density in an area increases average wages by 3.8-4.2%. This elasticity is lower than one estimated for China and India and around those estimated for Brazil and Colombia.

I also find a positive and strong effect for domestic market potential. The estimated coefficient is around 0.091-0.1, which is double that of density, suggesting that having access to other markets is the most important determinant of the productivity differences in Turkey.

This means that if the market potential of a province doubles (for example, employment density doubles in all other provinces), wages increase by 6.5%. This number is more than triple the figure of 0.02 for France, but smaller than the range of 0.13-0.22 for China.

Finally, I find that workers do not sort across locations based on their observable skills. This result is in sharp contrast with what is usually observed for developed countries, where a large fraction of the explanatory power of city effects arises from the sorting of workers (Combes and Gobillon, 2015). It is, however, very much in line with the results for China, suggesting that urbanisation patterns may be operating differently in developing countries.

Finally, I find a weak relationship between productivity (wages) and amenities, similar to that found in research on developing countries. This pattern can be explained either by the high correlation between density and amenities, or by the fact that workers in developing countries are not rich enough to forgo part of their income to live in areas with better amenities.

My findings corroborate earlier findings for developing countries, which show that while the main mechanisms of urban economies are present in the developing world, the current models need to be extended to capture the differences between Western cities and those in the developing world.

Further reading

Chauvin, Juan Pablo, Edward Glaeser, Yueran Ma and Kristina Tobio (2017) ‘What Is Different about Urbanization in Rich and Poor Countries? Cities in Brazil, China, India and the United States’, Journal of Urban Economics 98:17-49.

Combes, Pierre-Philippe and Laurent Gobillon (2015) The Empirics of Agglomeration Economies. Vol. 5, 1st ed. Elsevier.

Glaeser, Edward, and J Vernon Henderson (2017) ‘Urban Economics for the Developing World: An Introduction’, Journal of Urban Economics 98:1-5.

Özgüzel, Cem (2019) ‘Agglomeration Effects in a Developing Economy : Evidence from Turkey’, ERF Working Papers.