In a nutshell

Lebanon’s high public debt has led to high interest rates, real exchange rate appreciation, sluggish growth and the crowding out of consumption and investment by the private sector.

The economy relies heavily on the service sector, and more specifically on the tourism and banking sectors, while the agriculture and manufacturing sectors are still lagging behind.

Cuts in electricity subsidies, public pension reforms and reforms to combat tax evasion will re-establish confidence the Lebanese economy, which will subsequently be able to reduce interest rates and stimulate investment and growth.

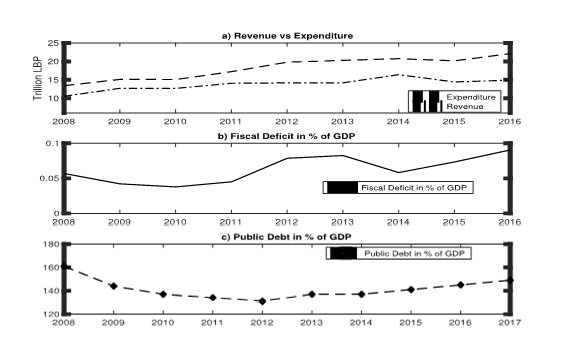

The conduct of fiscal policy in the emerging economy of Lebanon has recently become critical in determining the country’s future economic prospects. This is due to the accumulation since early 2000 of a significant public debt as a result of rampant corruption and consecutive current account and budget deficits, coupled with high levels of government spending and inadequate tax revenues (see Figure 1).

High public debt has led to high interest rates, real exchange rate appreciation, sluggish growth and the crowding out of consumption and investment by the private sector. With a debt-to-GDP ratio of 155% as of the end of April 2019, the financial distress of the public sector has become a major source of concern for Lebanon’s economy, rendering the country’s debt-financing programme unsustainable (Neaime, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2015b).

The expansion of the public sector has been at the expense of the private sector, which was traditionally the engine of growth for Lebanon’s economy. The relative weakness of the private sector, coupled with the rise of a less efficient and expanding public sector, underlies the urgent need for a more vigorous strategy of fiscal sustainability, given the impact it has on the economy (Neaime and Gaysset, 2017).

It is well known that a growing private sector increases growth and reduces poverty levels, unemployment and the brain drain (Neaime and Gaysset, 2018). Today, Lebanon’s economy relies heavily on the service sector, and more specifically on the tourism and banking sectors, while the agriculture and manufacturing sectors are still lagging behind.

Two major factors characterise the Lebanese banking sector. The first is the openness of the economy, which attracts significant offshore activity and facilitates international financial inflows in the form of bank deposits amounting to about US$150 billion at the end of 2018.

The second is the relationship with the government and the fact that Lebanese banks have taken on the responsibility of helping it with the debt burden. Through purchasing Lebanese treasury bills – which constitute a significant portion of their loan portfolios – since the early 2000s at relatively high interest rates, commercial banks’ balance sheet recorded record huge profits for more than 10 consecutive years.

But as the public debt is becoming unsustainable, holding public debt securities is becoming more and more of a risky venture for the banking system (Hakim et al, 2000, 2001; Neaime, 2000, 2012, 2015b).

More recently, Banque du Liban was put under pressure to purchasing a considerable portion of the latest issue of government bonds, constituting a clear signal that domestic and international sources of financing the government debt are drying up.

In addition, the latest increase in the minimum public wage and the total public wage bill, which is estimated at 120% of government revenues, have exacerbated even further the budget deficit. They have put further pressure on the central bank to hold more government debt through increases in the monetary base. This has resulted in even more pressure on the inflation rate, already estimated at 7% by the end of 2018.

According to the Ministry of Finance, Lebanon has accumulated a sizeable amount of public debt (US$86 billion at the end of March 2019), putting the country at the forefront of the MENA emerging economies with problems of debt unsustainability. Deficit financing has also affected private sector growth directly by crowding out private consumption and investment. It has subsequently lowered GDP growth rates to 1% in 2018 with a forecast of 0.2% for 2019, according to the World Bank.

In 2018, Lebanon posted a budget deficit of 11.2%, which was the highest in a group of developed and emerging economies that includes China, the euro area, the UK, the United States and other selected emerging economies (Neaime, 2015a; Neaime et al 2018). Government budget deficits have averaged 8.35% between 2010 and 2018, with the best figure being 5.92% for 2011 (see Figure 1).

As a point of comparison, the euro area had an overall deficit of 0.5% while Germany and Russia posted budget surpluses of 1.70% and 2.70%, respectively. Saudi Arabia had a budget deficit of 9.2% in 2018 as well as persistent deficits since 2014, but these are due to low oil prices and expansionary government policies in the oil-rich kingdom. With its debt-to-GDP ratio of 155%, the Lebanese case is a significant outlier and poses important threats to the sustainability of the country’s finances.

There have been reports of strikes and protests by employees at various government agencies thought to be at risk of cuts to pensions and benefits. These included protests by retired officers of the Lebanese military, employees at the Banque du Liban with a subsequent closure of the Beirut Stock Exchange, Ogero, and government employees at other institutions.

The General Confederation of Lebanese Workers announced the end of the strikes on Tuesday 7 May to give the government a chance to hammer out the differences. Among the measures included in the budget was an increase in taxes on income from interest on bank deposits from 7% to 10%, a measure strongly opposed by Lebanese banks.

In the Council of Ministers’ report entitled Lebanese Economic Vision, issued in 2018, the problems of Lebanon’s economy are cited as a highly volatile economy sustained by diaspora inflows (remittances) and challenges arising from corruption and the fiscal stance. (Another indicator of Lebanon’s weak fiscal stance is the fact that government salaries account for 9% of GDP versus a contemplated benchmark of 6%.)

As a consequence, this had led to a situation where per capita GDP growth has been 30% in the last 40 years compared with an average of 120%. The low rate of capital expenditure investment of 4% of the government budget compared with a benchmark rate of 10-20%, the decline in foreign direct inflows by 30% between 2010 and 2017 and the composition of diaspora flows into unproductive sectors such as consumption and real estate have compounded the issues facing the economy.

Lebanon’s austerity 2019 budget seeks to unlock $11 billion of new loans pledged by foreign investors at the Economic Conference for Development Through Reforms (CEDRE) conference in Paris in April 2018 by instituting a variety of so-called austerity measures, as the release of the funds is conditioned on the country being able to reduce its deficit by 5% over the next five years.

These austerity measures include a cut in electricity subsidies estimated at about $1.5 billion per year, public pension reforms and reforms to combat tax evasion.

If the government is able to reach a compromise on these polarising issues, the new funds that will be provided by foreign investors may be used to promote productive investments in several sectors that are viewed as key to Lebanon’s creating a self-sustaining economy. These sectors include agriculture, industry, tourism, financial services, the knowledge economy and diaspora inflows, with new infrastructure investment as one of the key enablers of the new economic model.

In short, it is crucial for Lebanon’s government to agree on the draft budget 2019 in a timely manner (immediately). Approving this year’s austerity budget will prevent an imminent currency crisis.

At this stage, Lebanon’s ability to attract further capital inflows and maintain confidence in its financial system is at its lowest. As a matter of fact, the country has recently been experiencing capital outflows and a loss of confidence in the Lebanese pound (LP) coupled with increases in the rate of dollarisation of bank accounts (conversion from pounds into dollars).

In a subsequent step, the government should eradicate the Electricity Du Liban (EDL) subsidy/deficit. In a last stage, the government should enhance tax collection and reduce tax evasion – before the introduction of any new tax hikes – and contain corruption, which has been rampant.

All of this will re-establish confidence in Lebanon’s economy, which will subsequently be able to reduce interest rates and stimulate investment and growth. The $11 billion CEDRE aid package will stave off a debt restructuring or debt default.

Reducing the budget deficit by 1% over a five-year period would mean that the rate of growth of debt would be contained. That is essential for a fiscal programme of debt reduction for the next five years.

But anti-austerity protests would mean that the budget would not be approved, which may subsequently lead to a loss of confidence in the ability of the central bank to maintain the pegged exchange rate regime ($1=LP1500). It may lead to a debt and exchange rate crisis.

Further reading

Hakim, Sam, Simon Neaime and CC Paraskevopoulos (2000) Perspectives on the Integration of Financial Markets – Global Financial Instability.

Hakim, Sam, and Simon Neaime (2001) ‘Performance and Credit Risk in Banking: A Comparative Study for Egypt and Lebanon’, ERF Working Paper No. 137.

Neaime, Simon (2000) The Macroeconomics of Exchange Rate Policies, Tariff Protection and the Current Account: A Dynamic Framework, AFP Press.

Neaime, Simon (2004) ‘Sustainability of Budget Deficits and Public Debt in Lebanon: A Stationarity and Cointegration Analysis’, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance 2(1): 43-61.

Neaime, Simon (2008) ‘Twin Deficits in Lebanon: A Time Series Analysis’, Lecture and Working Paper Series No. 2, Institute of Financial Economics, American University of Beirut.

Neaime, Simon (2010) ‘Sustainability of MENA Public Debt and the Macroeconomic Implications of the US Financial Crisis’, Middle East Development Journal 2: 177-201.

Neaime, Simon (2012) ‘The Global Financial Crisis and the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership’, Europe and the Mediterranean Economy.

Neaime, Simon (2015a) ‘Sustainability of Budget Deficits and Public Debts in Selected European Union Countries’, Journal of Economic Asymmetries 12: 1-21.

Neaime, Simon (2015b) ‘Twin Deficits and the Sustainability of Public Debt and Exchange Rate Policies in Lebanon’, Research in International Business and Finance 33: 127-43.

Neaime, Simon, and Isabelle Gaysset (2017) ‘Sustainability of Macroeconomic Policies in Selected MENA Countries: Post Financial and Debt Crises’, Research in International Business and Finance 40: 129-40.

Neaime Simon, and Isabelle Gaysset (2018) ‘Financial Inclusion and Stability in MENA: Evidence from Poverty and Inequality’, Finance Research Letters 24: 230-37.

Neaime, Simon, Isabelle Gaysset and Nasser Badra (2018) ‘The Eurozone Debt Crisis: A Structural VAR Approach’, Research in International Business and Finance 43: 22-33.

Figure 1: Fiscal deficit and public debt in Lebanon, 2008-2017

Source: World Bank Database & Lebanese Ministry of Finance.