In a nutshell

The clustering or ‘agglomeration’ of firms in the same sector within a region produces ‘positive externalities’, facilitating the growth of all firms and promoting investment in research and development (R&D) and innovation.

Technology plays a critical role in whether domestic firms benefit from agglomeration: policies should pay specific attention to enhancing the absorptive capacity of less technologically sophisticated firms.

Policies should support R&D investment and human capital acquisition to enhance the capacity of less technologically sophisticated firms to benefit from ‘spillovers’ from other firms and compete effectively.

Clustering of economic activity has long been seen as an important way to promote employment, firm growth and resilience. The clustering of industries in specific areas has improved industrial productivity in a number of countries.

Firm agglomeration in the same sector produces ‘positive externalities’, facilitating the growth of all manufacturing units within the sector. Clustering can also be an important driver of research and development (R&D) via a broad range of processes, such as ‘learning-by-doing’, labour market pooling and R&D cooperation between firms (Baltagi et al, 2012).

Porter (1998) emphasises the significant role of a cluster in a firm’s ability to innovate, as geographical concentration generates dynamic processes of knowledge creation, learning, innovation and knowledge transfer. As a result, the cluster becomes a centre of accumulated competence across a range of related industries and across various stages of production.

Location and firm performance in the southern Mediterranean

In a new study of location and firm performance in Italy, Tunisia and Turkey, we explore a series of questions: do firms localised in clusters of production in a region have higher productivity? How far is concentration of innovation in co-located firms able to increase productivity? And is there complementarity between domestic and foreign firms, with the former benefiting from the experience of other firms in the vicinity, especially large foreign multinationals?

Our analysis for each economy aims to provide a measure of spillovers from geographical and sectoral clustering of firms and from their innovation. We build specific indexes of agglomeration and innovation activity at the territorial level – provinces for Italy, governorates for Tunisia and regions for Turkey. We also use indicators of innovation by domestic firms and foreign multinationals.

Since our main goal is to analyse the effects of agglomeration and spillovers, especially from foreign firms, we use a number of proxy variables that capture the effects of these factors. Agglomeration is measured by the density of firms (the number of firms) or by the density of production activities (output). We also split this into the numbers of domestic and foreign firms in the same sector (defined at the NACE 4- or 2-digit level) and region/province (defined at the NUTS 2 or 3 level).

We use the number of domestic and foreign firms separately because the extent of spillovers could differ between the two. The first channel we try to capture consists of the spillovers between firms in the same industry (horizontal spillovers). We use three variables: the output share of the region in a sector’s output, and the number and output of firms by sector-region.

Then, we look at the R&D performed by domestic and foreign firms, which can be thought of as a channel of innovation spillovers. The share of output of R&D-performing domestic and foreign firms in the region/sector and the number of R&D-performing domestic and foreign firms in the region/sector are the two proxies considered for Tunisia and Turkey. For Italy, we consider the share of innovation proxied by intangible assets of domestic and foreign firms in the province and sector.

The third key issue is spillovers from foreign firms. For this purpose, we consider the shares of foreign firms in the region and sector.

As not all firms are able to benefit from spillovers and agglomeration effects, it is important to control for the role of firms’ absorptive capacity. Hence, we interact agglomeration and spillover variables with firm size (measured by the number of employees) and innovation (measured by R&D). These variables reveal whether large firms and innovation performers benefit more from agglomeration effects and spillovers.

The specific additional insights from our study come from the focus on agglomeration economies and innovation spillovers via a multidimensional approach, at the spatial and firm levels, in an effort to capture both regional characteristics of the economic systems and firm heterogeneity. The analysis at firm level is crucial to detect agglomeration economies as some factors are firm-specific because they are driven by factors relating to their different sizes, specific approaches to production and different innovation strategies (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2010).

We use analytical techniques that allow us to distinguish the direction of causality between clustering and productivity. We want to establish whether more regional clustering leads to higher productivity, ruling out the other direction of causality – that is, that higher productivity leads to more regional clustering.

Results

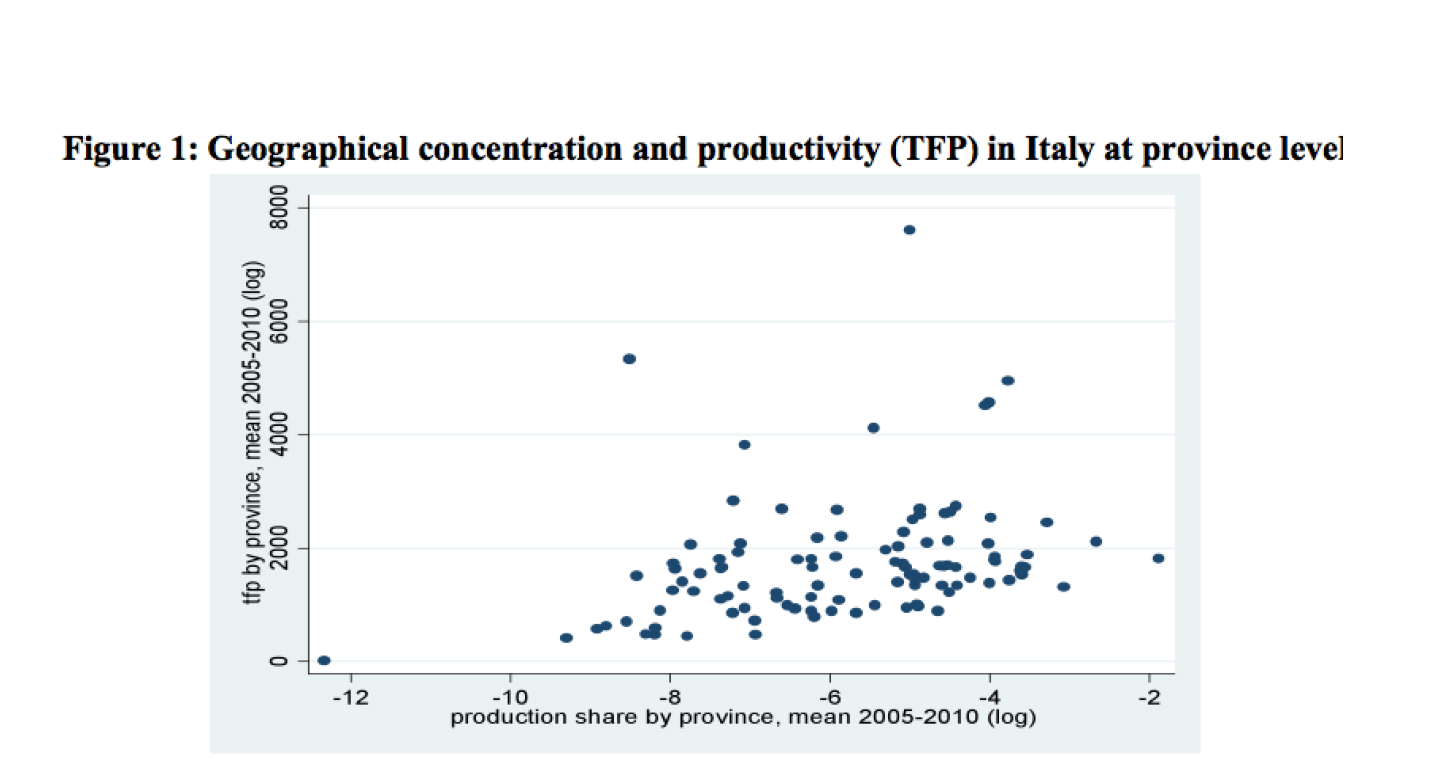

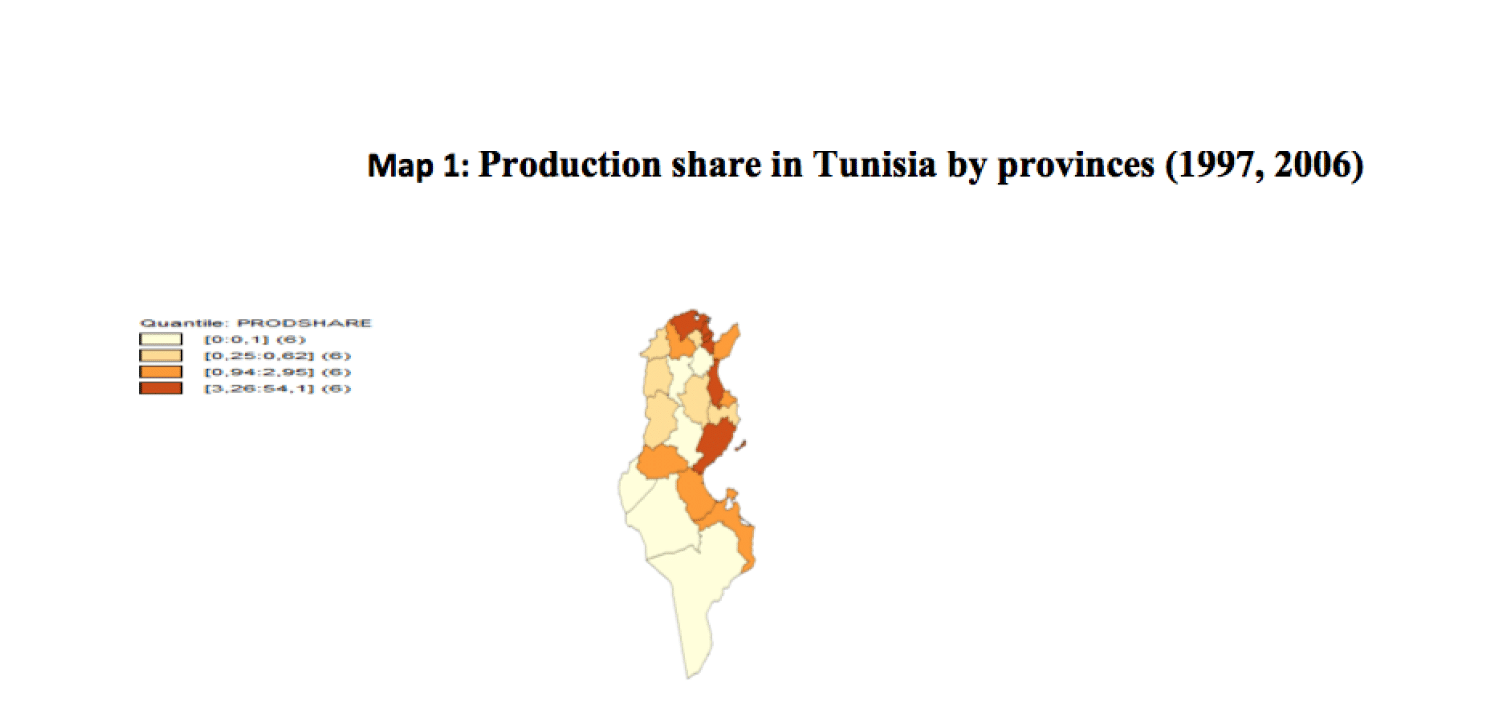

Agglomeration externalities measured by different proxies show a strong positive effect on output and productivity (as Figure 1 shows for the case of Italy, and Map 1 for the case of Tunisia). They confirm the presence of positive externalities due to specialisation economies and intra-industry spillovers.

Two other agglomeration indicators – the number and output of foreign firms and domestic firms in the region at sector level – are both significant. But while there are positive externalities from foreign firms’ agglomeration, the externalities from agglomeration of domestic firms are negative, suggesting congestion effects.

In terms of the innovation spillovers from the number and output of domestic and foreign firms that carry out R&D, we find positive and highly significant returns. In addition, we find evidence of large spillovers from foreign direct investment at the local level. The results for Turkey also suggest that spillovers from foreign firms are stronger than those from domestic firms. Besides, there seem to be no spillovers specific to large firms, but there are spillovers specific to technologically more sophisticated firms.

For Italy, we also find evidence of agglomeration and innovation spillovers at the local level on firm productivity. But horizontal spillovers from agglomeration at the local level stem mainly from non-multinational firms rather than from the localisation of foreign multinationals.

Firms also benefit from innovation by neighbouring domestic firms in the same sector. Agglomeration economies and innovation spillovers are more beneficial to small firms than to large ones, and firms’ technology endowment is relevant to catch these spillovers.

Our analysis of Tunisia produces similar results. Overall, there is evidence in favour of a positive impact of specialisation economies, as suggested by the positive impact of the concentration of domestic firms and domestic R&D performers as well as by the positive impact of higher shares of a sector in a region. But we don’t find innovation spillovers from the localisation of foreign firms in the region.

Policy implications

In terms of policy, there is considerable prior evidence that firms in the same industry benefit more from each other as they are more technologically similar. Sector distance also matters as it may facilitate the flow and absorption of knowledge among firms in an open economy.

We find support for just such conclusions in our three country studies. But technology plays a critical role, and policies should pay specific attention to enhancing the absorptive capacity of less technologically sophisticated firms.

The experience drawn from this analysis supports the idea of identifying key drivers and patterns of localised production, and provides a benchmark to analyse the efficiency of clusters of small and medium-sized enterprises in southern Mediterranean countries. In particular, the results may be useful to support the projects of Euro-Med clusters of cooperation on industry and innovation, and the emerging innovation clusters based in Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia.

The downside that should be avoided is the increasingly unbalanced process of regional growth in most Mediterranean countries, which can lead to large income and employment gaps across regions, and the consequences of mass migration and concentration of population in large cities and along the coast, degradation and isolation of internal areas, environmental abandonment and impoverishment that the recent decades have witnessed.

Reallocation of resources to less developed regions could be costly and counterproductive given that regional tax incentives to poor regions may shift jobs away from territories that do not receive the subsidy, rather than create new ones. Instead, the policy target for the government should be investing in transport infrastructure, easing access to housing and developing regional complementarities.

Such policies would expand job opportunities for the people outside the core regions, which are mainly concentrated along the coasts. They would also lead in the longer term to a more sustainable convergence of standards of living among regions, reducing the exploitation of resources along the coast and the pressure on natural resources.

Policies should also support R&D investment and human capital acquisition to enhance the capacity of less technologically sophisticated firms in order to compete and benefit from surrounding spillovers.

Further reading

Baltagi BH, PH Egger, M Kesina (2015) ‘Firm-level Productivity Spillovers in China’s Chemical Industry: A Spatial Hausman-Taylor Approach’, Journal of Applied Econometrics 31(1).

Bloom, N, and J Van Reenen (2010) ‘Why Do Management Practices Differ Across Firms and Countries?’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(1): 203-24.

Ferragina, AM, S Ghali and E Taymaz (2018) ‘Spatial Proximity and Firm Performances: How can Location-based Economies Help the Transition Process in the Mediterranean Region? Empirical Evidence from Turkey, Italy and Tunisia’, FEMISE Research project Fem 41-09.

Porter, ME (1998) ‘Location, Clusters and the ‘New’ Microeconomics of Competition’, Business Economics 33(1): 7-17.

This article is based on research produced by FEMISE (FEM41-09) and which received financial assistance from the European Union within the context of the FEMISE-EU project.

A policy briefing summarising the research findings is available here.