In a nutshell

Equity issuance is an important channel through which capital inflows affect real economic activity in emerging market firms, reducing the cost of equity finance for new investments.

These advantages accrue disproportionately to large firms, which suggests that it is important to distinguish between large and small firms when gauging the effects of equity market liberalisation.

Capital inflows imply more than a simple transfer of equity ownership from domestic to foreign investors: they result in substantial new equity funding – for every $1 million of emerging market equity purchased by foreign investors, the value of seasoned issuance proceeds increases by $160,000.

Capital inflows are prevalent in emerging market economies. Macroeconomic research suggests that liberalisation of equity capital flows is associated with a boom in the stock market, higher productivity, and increased investment and economic growth in the recipient countries (see Kose et al, 2010, for a summary). Still, relatively little is known about the channels through which equity inflows affect financial and real economic activity.

Corporate finance research shows that foreign financing leads to better financing options, greater visibility and improved corporate governance (Karolyi 2006). Moreover, loose monetary policy in the United States can allow emerging market firms to take advantage of improved financing as foreign investors seek out carry-trade opportunities across markets (Baskaya et al, 2017; Bruno and Shin, 2017; Chari et al, 2017).

But we have not yet identified specific links between the increased supply of foreign capital and firm financing patterns. One reason: it is hard to track the influence of foreign investors on firm behaviour if we cannot identify the nationality of the owner of each security, at every time.

Foreign investors can buy equity from domestic investors, simply changing the composition of ownership of a firm. Therefore, foreign purchases of equity have no mechanical connection to the issuance of that equity.

In theory, however, interest from foreign investors leads firms to issue more equity. To the extent that foreign interest raises the supply of funds available to emerging economies, the riskless interest rate should fall. Improved risk pricing of equity through cross-border diversification should reduce the equity risk premium. Both of these effects should reduce the cost of issuing equity, and lead to more issuance (Henry, 2007).

Firm-level issuance

In our new study, which analyses firm-level issuance and the uses of the funds that are raised, we find that greater equity capital inflows are positively related to additional equity financing (Calomiris et al, 2018).

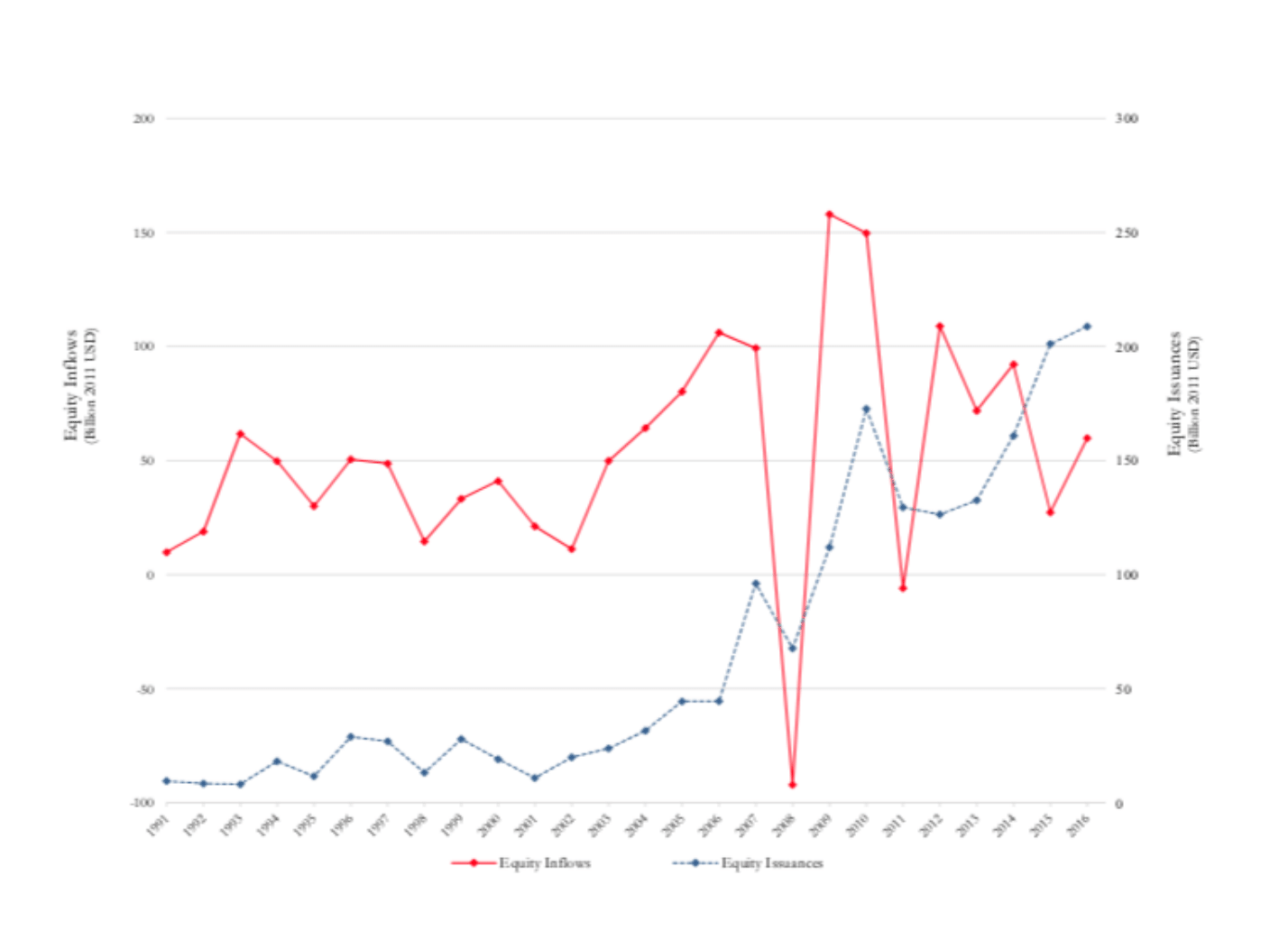

We find a positive correlation over time between the aggregate amount of equity investing by foreign investors into our sample of countries and the total value of seasoned equity raised by firms in those countries. Figure 1 plots the total value of equity issued by firms in 25 emerging market countries on the right-hand axis, and total portfolio equity inflows to those emerging markets on the left-hand axis.

Figure 1:

Emerging market equity issuances and equity capital inflows, 1991-2016 (billions of 2011 US dollars)

Source: Calomiris et al (2018).

There is substantial heterogeneity in firms’ responses to capital inflows. Large firms (as measured by market capitalisation) have a larger issuance response to inflows than small firms. This is because foreign investors tend to target large firms when they invest in emerging market equity.

By analysing what influences the decisions of international investors about the destination of their equity investments in emerging market firms, we distinguish the component of equity inflows that reflects changes in investors’ supply of funds from inflows that result from changes in the demand for capital.

The key to identifying supply-side shocks is that for a given amount of total capital inflows into emerging markets, positive shocks to other countries’ attractiveness to foreign investors are negative shocks to the subject country’s supply of funds. Inflows to a subject country, instrumented with different variables (the lagged weight of a country in the MSCI Emerging Markets stock index, the sum of other countries’ total equity value, and other countries’ volume of equity issuances) should (and do) lead publicly traded firms in the subject country to raise more equity.

Emerging market equity issuers that respond by issuing more equity tend to use that equity to fund large increases in corporate investment. They also accumulate cash and inventories, increase acquisitions and reduce long-term debt. For every $1 million raised in a seasoned equity offering, issuers spend on average $700,000 on fixed capital investment four years after the issuance.

An important channel

Our findings complement analyses of how firms use new capital market financing (Kim and Weisbach, 2008). This new evidence also helps to explain observed large effects of equity inflows on emerging market countries’ productivity, investment and growth.

Equity issuance is an important channel through which capital inflows affect real economic activity in emerging market firms, reducing the cost of equity finance for new investments. Those advantages, however, accrue disproportionately to large firms.

This suggests that it is important to distinguish between large and small firms when gauging the effects of equity market liberalisation. Lower cost of funds for non-financial large issuers might create a competitive advantage for them. At the same time, it is possible that large issuers might share some of the benefits of their access to international investors with other firms. Those other firms could benefit indirectly from more abundant trade credit, or increased demand for their products and services.

Also, if equity issuances reduce issuers’ demands for local bank debt, that could make it easier for non-issuers to borrow locally. Financial firms might also use their new equity issuance proceeds in support of greater lending to local firms. These two influences could be particularly beneficial for small and medium-sized firms.

Future research could shed light on whether selective reductions in the cost of equity promote greater efficiency in the economy, or whether they create inefficiencies by increasing the market power of a small number of large firms.

Further reading

Baskaya, Y, J di Giovanni, S Kalemli-Ozcan and M Ulu (2017) ‘International Spillovers and Local Credit Cycles’, NBER Working Paper No. 23149.

Bruno, V, and HS Shin (2017) ‘Global Dollar Credit and Carry Trades: A Firm-level Analysis’, Review of Financial Studies 30(3): 703-49.

Calomiris, C, M Larrain and S Schmukler (2018) ‘Capital Inflows, Equity Issuance Activity, and Corporate Investment‘, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8405.

Chari, A, KS Stedman and C Lundblad (2017) ‘Taper Tantrums: QE, Its Aftermath, and Emerging Market Capital Flows’, NBER Working Paper No. 23474.

Henry, P (2007) ‘Capital Account Liberalization: Theory, Evidence, and Speculation’, Journal of Economic Literature 45(4): 887-35.

Karolyi, G (2006) ‘The World of Cross-Listings and Cross-Listings of the World: Challenging Conventional Wisdom’, Review of Finance 10(1): 99-152.

Kim, W, and M Weisbach (2008) ‘Motivations for Public Equity Offers’, Journal of Financial Economics 87(2): 281-307.

Kose, A, K Rogoff, E Prasad, and S-J Wei (2010) ‘Financial Globalization and Economic Policies’, in Handbook of Development Economics Vol. 5 edited by D Rodrik and M Rosenzweig, North-Holland.

This column was first published at VoxEU.org – read the original article.