In a nutshell

Turkey’s growth rate of per capita real GDP has been three times higher in the first terms of single-party governments than in their later terms.

As the number of parties in government and the ideological distance between them increase, Turkey’s growth rate falls.

If the political fragmentation caused by coups could have been avoided, and the checks and balances prevailing in the first terms of single-party governments maintained in their later terms, per capita real GDP in Turkey would be 5.5 times higher than it is today.

Sixty-eight years have passed since 1950, when the first fair and direct election took place in Turkey and power changed hands for the first time. The country was ruled by single-party governments in 39 of those years, by coalitions in 21, by the military in five and by minority governments in three.

While single-party governments all lasted at least two legislative terms, the rest rarely lasted even one term. Had it not been for the coups, single-party governments would be even more prevalent and longer lasting, and coalition governments less fragmented.

Coup-induced cycles

In Turkey, conservative voters – in an economic and/or cultural sense – show a tendency to unite under one roof. Most of the time, they receive more than sufficient public support to capture a majority of the seats in parliament.

Each time that happens, however, their government is toppled by coups and their party split because they are perceived as a threat: to the secular and Western orientation of the country; and to the guardianship roles of the military and the judiciary in the established order.

All successful coups have taken place when conservative parties were in power. Only one party was ruling in all of them, except on one occasion when two parties were in a coalition but both were conservative. In each case, the military returned the country to electoral democracy after taking over for a few years, either directly or through a civilian government that they imposed, making some institutional changes to strengthen their guardianship role, which had eroded over time.

A string of ideologically incompatible coalition governments (those in which at least one half of the junior parties were from the opposite wing of the political spectrum than the primary incumbent party) followed each coup because pieces of the fragmented conservative parties were not allowed to form a government by themselves. They were forced to partner with a statist party so that the government could be controlled more easily.

In each case, however, the conservative parties eventually managed to get together again – first in a coalition government and then in a single-party government – which then led to a new coup and another period of coalitions.

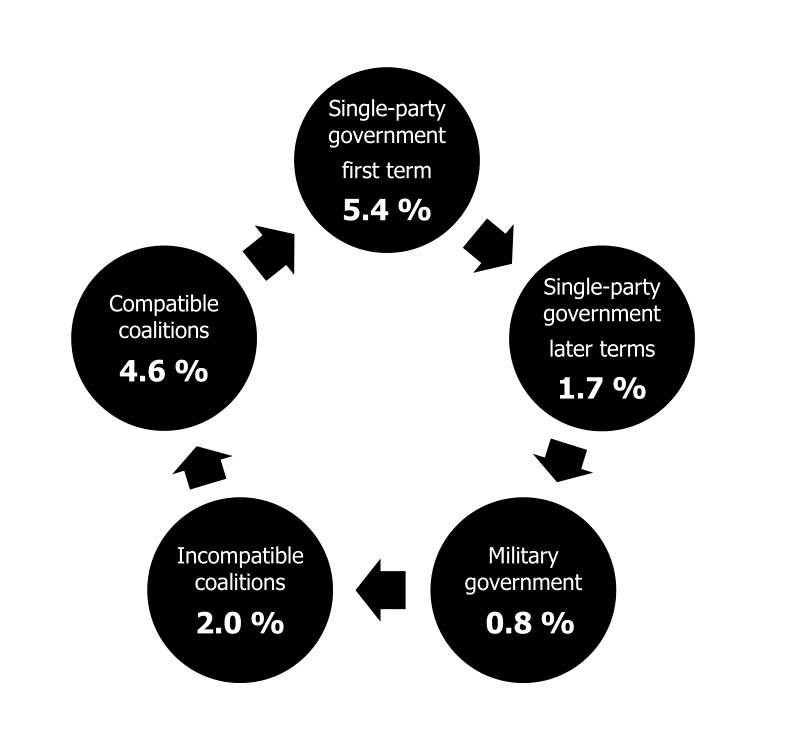

The various types of Turkish governments ranked according to their economic growth performance from the best to the worst are as follows: single-party governments in their first terms; ideologically compatible coalition governments; ideologically incompatible coalition governments and single-party governments in their later terms; and military governments.

Consequently, the political cycles induced by coups have created parallel economic cycles, as demonstrated in Figure 1, with economic performance going from very good to below average to really bad, then moving closer to average, then to good and very good again.

Thus, coups have not only caused instability in the economy, but also reduced its growth rate. It is not by chance that economic performance has differed under different types of governments. Growth typically exhibits an inverted-U pattern over the tenure of a long-lived government, and declines as the number of ruling parties and the ideological distance between them increase.

Political fragmentation and economic performance

There are many reasons why government fragmentation affects its performance. Ruling parties undertake projects that bring more benefits to their supporters than costs, even when the costs to the general public exceed the benefits.

Then government spending and deficits become larger too, which causes inflation and interest rates to rise and private investment to fall. This occurs under all governments, but to a much lesser extent under single-party governments and coalitions that are less fragmented. This is because more of the costs are internalised in the case of larger ruling parties and under coalitions with ideologically similar partners that represent similar interests.

Multi-party governments also indulge in inefficient projects because they have shorter life spans than single-party governments and, as a result, they have shorter time horizons and lower discount factors. Consequently, they appease their supporters with more government money and shift the burden of higher expenditures to future governments.

The poor incentives given to coalition governments by the electorate is yet another reason why economic performance suffers. Under such governments, it becomes more difficult for voters to assign responsibility and sanction ruling parties for their performance. This results in voters giving less weight to the economy in their evaluations. They also hold junior partners less responsible for economic conditions than the primary incumbent, and sometimes not responsible at all.

Furthermore, in ideologically incompatible governments, incentives turn into disincentives for the junior members. Ruling parties that are rewarded less for a good economy will have less incentive to perform well. They are more likely to sacrifice economic goals for other considerations and try to get votes through populist policies.

When the parties in coalition governments are not held equally accountable, this creates friction between the partners, delaying critical decisions and reducing the expected lives of the governments, which in turn generates uncertainty, lowering investment. Minor incumbents with nothing to lose, or even something to gain, often drag their feet on reforms of they approve just to deny their main coalition partner a vote gain.

As Figure 1 shows, growth under ideologically incompatible coalitions is substantially less than under compatible ones.

Government duration and economic performance

The effect of ruling party duration on growth is initially positive and subsequently negative. New governments typically make substantial changes in macroeconomic policies, which by creating uncertainty dampen investment and growth. This uncertainty gradually dissipates as investors observe government’s policy behaviour.

But as the marginal returns from the stabilisation of policy expectations diminish over time, pressure by special interest groups to redistribute resources rise. Market interventions to create rents for these groups distort incentives, drawing resources from efficient uses. Lobbying efforts also eat up resources. Thus, the extended duration in power of ruling parties eventually leads to institutional sclerosis and deteriorating economic performance.

The existence of veto players (individuals or institutions whose agreement is required for a change in the status quo) plays an important role on the growth-duration relationship. Veto players initially contribute to stability by making policy changes less likely. But they later reduce the government’s ability to respond to changing economic conditions and to reverse prior policy mistakes. In addition, when there are too many veto players, as in divided governments, ruling parties can engage in rent distribution through ‘log-rolling’ and ‘pork-barrel’ legislation.

Too few or no veto players can also be a problem. In the absence of effective veto players, ruling parties become more ‘clientelist’. Also, with very few checks and balances, it becomes more difficult to catch and correct mistakes, easier to make mistakes and easier to create uncertainty with arbitrary policy changes.

Initially there were a reasonable number of veto players in Turkish single-party governments but these got eliminated over time. All such governments were formed by parties that were established only a few years before taking office.

At the beginning, their leader was essentially the first among equals. The party’s members of parliament and cabinet, and provincial officials were an integral part of decision-making. Much needed structural changes and policy actions delayed under the preceding era of coalitions were all undertaken during the first terms of single-party governments, when the growth rate peaked.

But lacking a strong tradition and legal framework for intra-party democracy, power eventually got concentrated in the centre and in the hands of the party leader. Concerns about losing the subsequent election, and fears of providing an excuse for the military to conduct a coup, initially restrained the ruling conservative parties.

But from the beginning of their second terms, the limited independence of regulatory bodies and the central bank has been curtailed and competent technocrats who opposed populist policies were replaced. Members of parliament stopped speaking their minds freely, as those too critical of government risked being removed from their party’s candidate lists in the next election.

Often press freedoms suffered too. With no effective veto players and deliberation, policy mistakes were not noticed, or when they were noticed, they went uncorrected. Creative ideas diminished, discretion replaced rules and policies changed abruptly and arbitrarily, often not in response to changing economic conditions. Corruption and rent-seeking increased. Consequently, the growth rate of per capita real GDP in the second and later terms of single-party governments is only one-fifth to one-half of their first terms.

The fact that this pattern has occurred under all single-party administrations, which ruled decades apart, shows that it cannot be attributed to specific factors related to a leader or a period. Economic performance was far better under compatible coalitions than during later terms of single-party governments. Lack of checks in the latter and parties acting as veto players in the former made the difference.

Concluding remarks

In short, coups have had long lasting consequences not only politically but also economically. Their adverse impacts in Turkey have not been restricted to periods of direct military rule but continued way into the future through the guardianship system that they established. Military interventions not only caused economic growth to be lower but also to fluctuate in a cyclical manner.

Coup-induced political business cycles are distinct from election-induced political business cycles. Although there is awareness in Turkey of the latter, the dynamics underlying the former, even their existence, is not recognised. Consequently, coalitions and poor economic performance under them are viewed as natural phenomena that can be avoided only through tinkering with the electoral and governmental systems.

For example, the unusually high 10% national vote threshold for a party to gain representation in the Turkish parliament was instituted to reduce the effective number of parties and thus the likelihood of coalition governments. Putting an end to coalition governments was also the main justification for the recent replacement of the parliamentary system with a presidential one.

In fact, if coups could be avoided, coalitions would be much less frequent, and when they occurred, they would be formed voluntarily by ideologically compatible parties, under which economic growth is reasonably good.

Thus, curtailing coups will produce better economic outcomes. In that regard, the failure of the last two coup attempts in 2007 and 2016 can be taken as a good sign.

But to move to a fully consolidated democracy, it is necessary to fill the vacuum created by dismantling of the military-judiciary guardianship system with new political institutions that provide strong checks and balances. For example, the power of the legislature has to be increased to match the powers of the executive, which are now increased and concentrated further.

To that end, we should consider instituting single-member parliamentary districts for which party candidates are chosen through primaries rather than by party leaders, and winning candidates determined through two-round elections just as with the presidency. This will also render legislators more responsive to their constituents than to their parties and leaders.

Reforms to make the judiciary independent and impartial would also be useful, so that it neither controls the government nor is controlled by the government, and that it sees its main duty as protecting citizens against the state and not the other way around.

Improving the quality of the country’s democracy is of paramount importance for its economic wellbeing. Had the average growth rate of per capita real GDP since 1950 been the same as the rate achieved during the first terms of single-party governments, Turkey’s per capita real GDP today would be 5.5 times higher.

Further reading

Akarca, Ali T (2017) ‘Economic Voting under Single-Party and Coalition Governments:

Evidence from the Turkish Case’, ERF Working Paper No. 1128.

Akarca, Ali T (2018) ‘Political Determinants of Government Structure and Economic Performance in Turkey since 1950’, ERF Working Paper No. 1241.

Akarca, Ali T (2018) ‘Single-Party Governments as a Cause and Coalitions as a Consequence of Coups in Turkey’, in Turkish Economy: Between Middle Income Trap and High Income Status edited by AF Aysan, M Babacan, N Gür and H Karahan, Palgrave Macmillan.

Figure 1:

Average growth rate of per capita real GDP over the coup-induced political business cycle, 1950-2015