In a nutshell

Insecurity, socio-cultural complexity among the G-5 and the imperative to ‘do no harm’ explain donor inaction in the Sahel.

But the cost of investing in the public good that security and development in the G-5 represents will be far lower than managing the costs of an extended crisis.

Simultaneous progress on security, education and agricultural development are needed to tackle demographic, economic, social, environmental and institutional vulnerabilities.

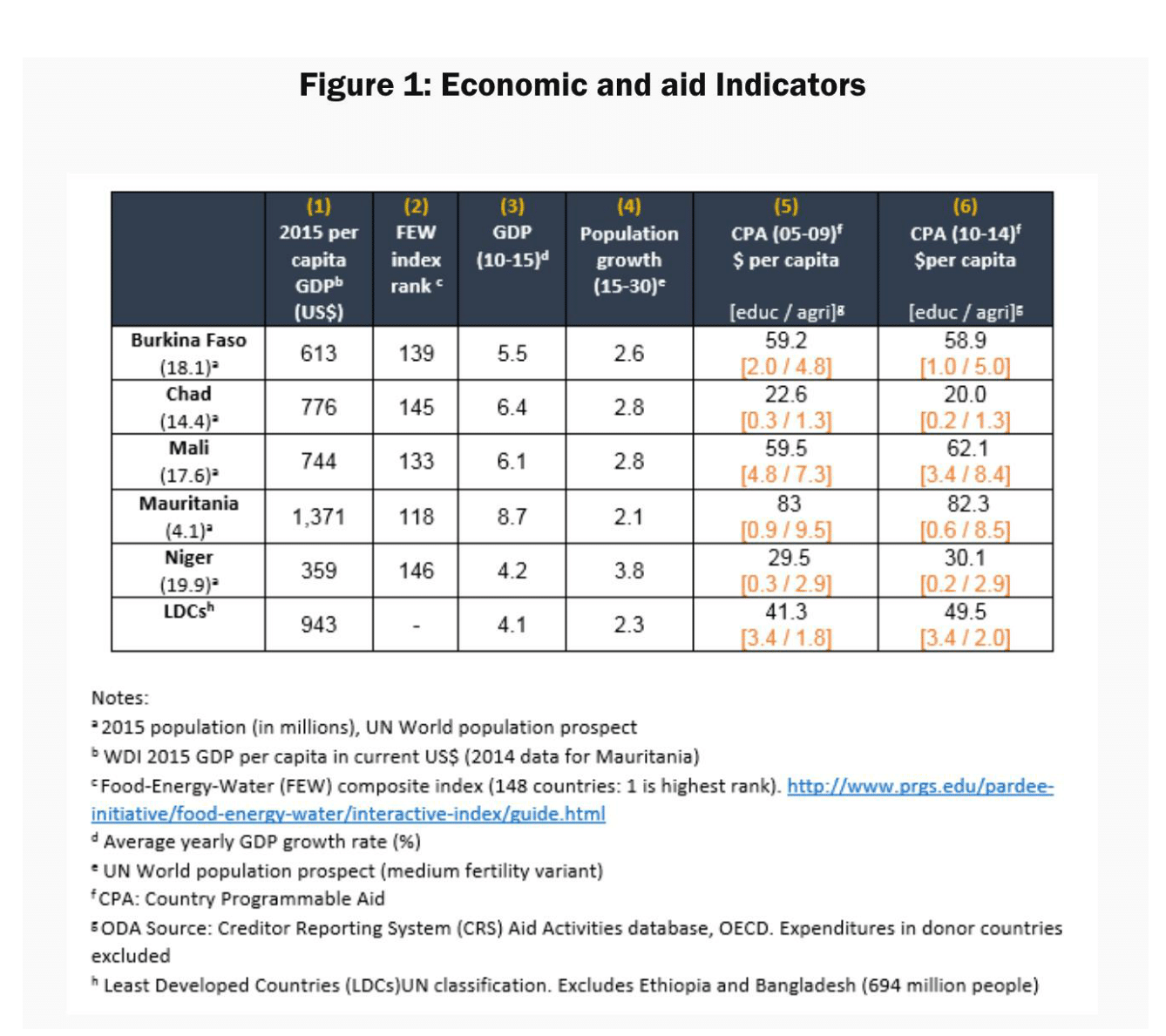

Conditions in the Sahel are grim – some say emigration is the only recourse as economic, social, demographic and environmental vulnerabilities worsen there. The Sahel – Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger – often called the ‘G-5’ in recognition of the group set up to deal with their precariousness – are either in, or are about to fall into, poverty and conflict traps (see Figure 1).

These traps emerged following donor-led structural reforms in the 1990s when tough spending choices meant security was sacrificed for investments in education and other sectors. As a result, the G-5 and neighbouring countries have edged toward ‘failed state’ status.

Figure 1:

Economic and aid indicators

‘Linking security and development – A Plea for the Sahel’, a report by Sylviane Guillaumont, myself and others from the Fondation pour les études et recherches dans le développement international, summarises the insights of 17 actors and observers involved in the Sahel, including military personnel, academics, diplomats, dignitaries and former ministers, and non-governmental organisation (NGO) representatives.

All 17 respondents recognised that there is no development without security and vice versa. They spoke to the urgency of the situation, making it clear that the window of opportunity for a much-needed ‘big push’ in foreign assistance is closing fast.

The Sahel: breeding ground for violence

Violence in the Sahel is caused by complex factors, including the grievances of nomadic Tuaregs, cocaine trafficking that emerged in 2005 on top of other traditional trafficking, and the flood of thousands of unemployed soldiers and armed men into the region after the fall of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Added to this are family conflicts over land, national grievances and tensions among traffickers.

The situation was compounded when Algeria expelled Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, which led bad actors towards the Sahel. Armed banditry spread and day-to-day insecurity grew. Populations in the region, already on the verge of poverty, fell into conflict traps. In the face of such fragmentation, governing became ever more difficult.

Rapid population growth and a youth bulge have contributed to low per capita income growth and widespread vulnerability. Though primary school enrolments are up, time spent in school tends to be brief and the public education system is not equipping graduates for jobs in the agriculture sector. Public sector jobs are disappearing and employment in manufacturing and services are reserved for those with secondary and higher qualifications.

Youth feel excluded and held back by deeply entrenched intergenerational hierarchies. Salafist schools have stepped in to fill voids, especially in the northern Sahel. Many Koranic schools are only preparing their students for entry into a society dominated by religion.

The international response: delayed and imbalanced

Support for the Sahel, starting with the European Union’s (EU) pledge of five billion euros in April 2011, has been slow to materialise. A terrorist attack in Mali in early 2013 prompted a mix of grant aid and military interventions. In November 2015, a detailed plan for spending the promised EU funds was adopted. Funding was increased by one billion euros through an urgency fund, but no one knows when the money will be disbursed.

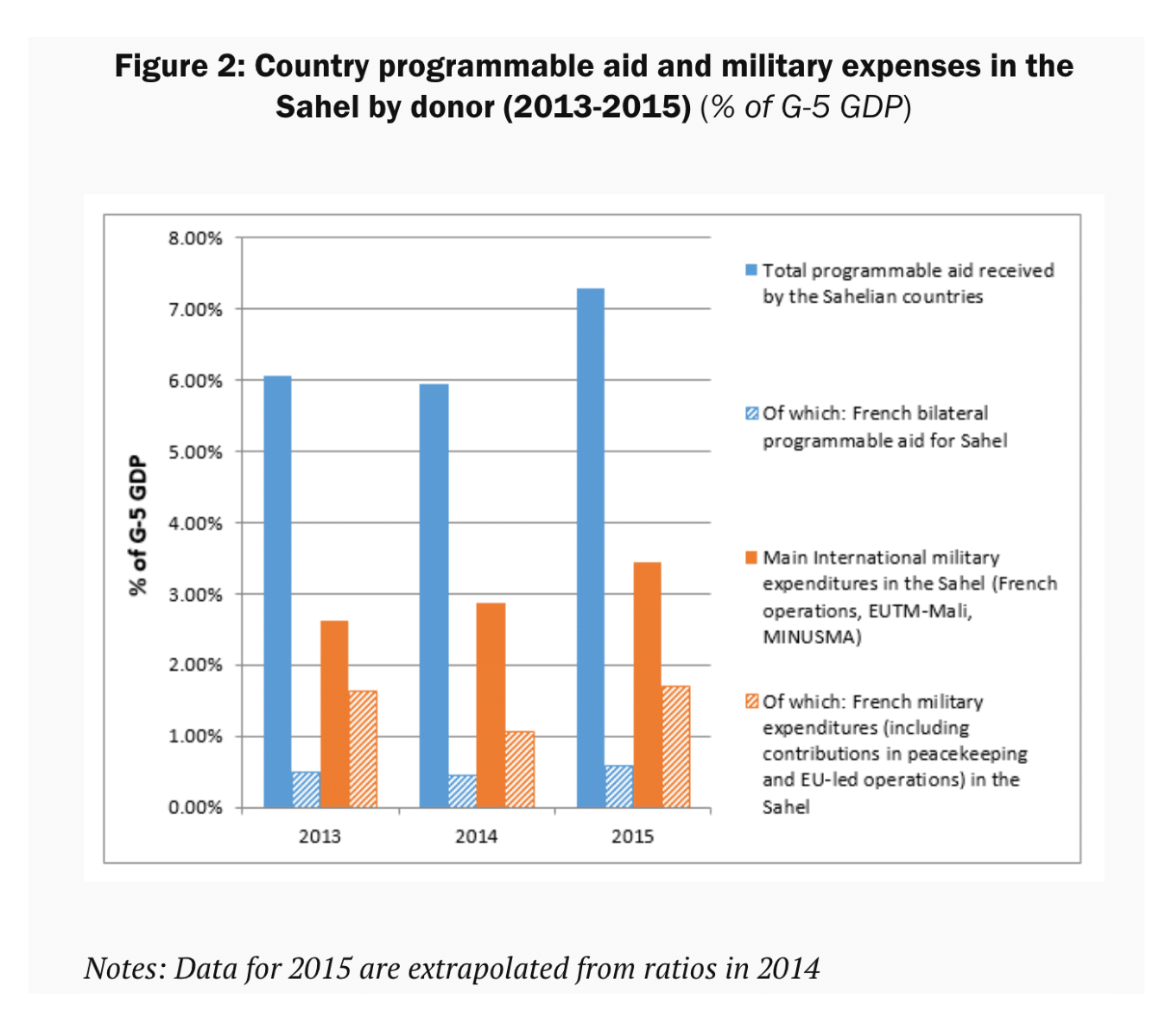

While the international community continued to focus on development in the Sahel, France has shifted toward military support (see Figure 2). Following a series of military interventions in Mali, parties to the conflict signed a peace agreement in 2015, allowing a lull that is tenuous at best. As one interviewee said, ‘There is no point in building schools or installing water supply points if we’re afraid to go to the market or send our girls to fetch water.’

Figure 2:

Country programmable aid and military expenses in the Sahel by donor (2013-2015) (% of G-5 GDP)

Source: Laville (2016).

Donors have long been reluctant to fund military or police spending, in part because it cannot be counted as official development assistance (ODA). This amounts to a failure to recognise the need to fund African security forces so they can protect civilians. Also, capacity-building for security forces takes time and donors want to have confidence in overall governance before supporting security-building.

The way forward: boost funding and focus on primary education and agriculture

Insecurity, socio-cultural complexity among the G-5 and the imperative to ‘do no harm’ explain donor inaction in the Sahel. In 2014, ODA shares for health were respectable with France at 28%, the United States at 21% and multilateral donors at 9%. By contrast, per capita funds allocated to agriculture and especially to education – the two sectors singled out by respondents in our report – were generally low (see Figure 1).

More funding for day-to-day security and for economic development is urgently needed. Everyone we interviewed concurred that the cost of investing in the public good that security and development in the G-5 represents will be far lower than managing the costs of an extended crisis.

All interviewees were also adamant that the socio-cultural complexity in the Sahel calls for a multidisciplinary approach – researchers, diplomats, ethnologists, humanitarians, and defence and development experts – with each group working in its respective area of expertise. Success will also depend on close cooperation between the public and private sectors working with local and international NGOs.

Simultaneous progress on security, education and agricultural development are needed to tackle demographic, economic, social, environmental and institutional vulnerabilities.

Several success stories offer room for hope. The first is in agriculture, where rural development activities in the Agadez and Tahoua regions in Niger as well as an agro-ecology project in Keita, also in Niger, appear to hold promise.

A second relates to the reintegration of fighters in Côte d’Ivoire through a disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration project. Recovery requires a big push in assistance to reduce day-to-day insecurity as well as a targeting of ODA toward projects with a quick return.

For example, initiatives to promote the inclusion of professional content into school curricula and mini-projects in rural areas, combined with projects with longer-run returns (for example, improvements in the quality of teaching and of security forces) may offer a good starting point.

This column was originally published by Brookings in December 2016. Read the original article.