In a nutshell

Governments in middle-income Arab countries need to improve tax fairness by establishing more equitable, progressive and transparent systems.

Improving tax and customs administration, simplifying coding and regulation, and investing in technology to improve transparency can enhance compliance and increase the potential tax base.

In addition to national tax reforms, a global standard for information exchange is needed to tackle illicit financial flows as well as cross-border tax evasion and tax avoidance.

A fair and progressive taxation system supports the principles of inclusion and equity through collection practices oriented around the ability to pay, and through raising revenues for financing development priorities, including pro-poor initiatives.

Yet Arab countries have systematically low tax collection rates relative to the size of their economies, and little attention is paid to ways of improving taxation systems to raise more revenue. If at all, policy-makers have put all their efforts into raising indirect taxes, such as VAT (value added tax), which by their nature are regressive, placing a higher tax burden on the lower middle class and the poor than on the rich.

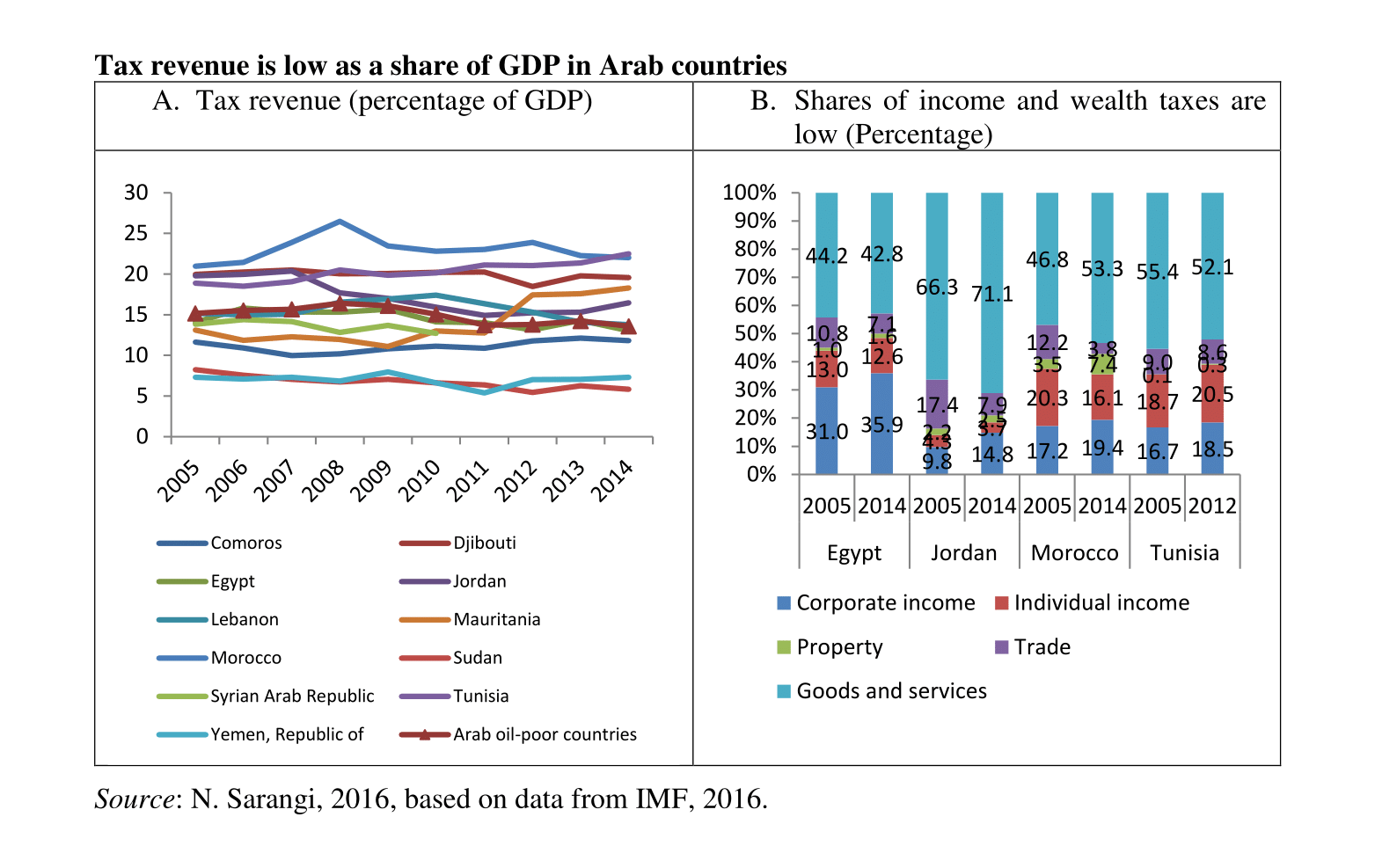

The share of taxes in GDP thus varies between 10% and 20% in most Arab middle-income countries (Figure 1A). The exceptions are Morocco and Tunisia, which have undertaken some progressive reforms in income tax recently and where the share is now about 23%.

Indirect taxes, like those on goods and services, constitute the major share of taxes in the tax systems of middle-income Arab countries. Furthermore, this share has increased in some countries over time (Sarangi, 2016; and see Figure 1B). Wealth taxes constitute a negligible share of total tax revenue in most countries in the region. Globally, taxes on property form around 7% of total tax revenue, a much higher share than in Arab countries.

From a political economy perspective, this outcome is not difficult to explain. A prominent feature of ‘rentier states’ is that the bulk of public revenues are generated from external sources such as oil exports. But while this may make sense for resource-rich countries, it does not explain why there is a persistently low tax-to-GDP ratio in resource-poor Arab countries, such as Egypt, Jordan and Syria?

There are two broad explanations. Up until recently, most middle-income Arab countries avoided high taxation to avoid stirring popular demands for fiscal governance reforms, which would necessarily entail higher transparency and voice and accountability.

But such a trade-off is no longer economically feasible, especially as the intra-regional spillovers from the oil-rich countries to the oil-poor ones that may have relieved budget pressure in the past (foreign direct investment, official development assistance, tourism and worker remittances) have significantly contracted since 2011.

Oil-rich countries are coming under fiscal pressure due to rising military expenditures and lower oil prices. Hence it would be fair to say that the time is right for region-wide fiscal policy reforms that enact fair and progressive taxation systems. That is essentially the main message of the most recent report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA, 2017a).

One of the main arguments in the report to substantiate this claim is the significant potential to improve equity, given that income and wealth taxes constitute a negligible share of total tax in the current system despite evidence of increasing wealth inequality. The policy-relevant question is how to make this happen.

We argue that two key policy shifts are needed to reform current tax systems.

First, make tax systems more fair and progressive – and simplify administrative procedures for better tax compliance

Governments need to consider improving tax fairness by establishing more equitable, progressive and transparent systems that clearly rationalise exemptions. Given growing inequality and the relatively low tax burden on the top income decile and the even lower burden on the richest 1% in some countries, there is clear room for improvement. Experience from other countries shows that this is possible if there is political will.

Even among lower-income countries, direct tax collection could increase from 2% to 4% of GDP. Property tax can be an effective tool to increase revenue and improve equity, but currently, these taxes are low and largely evaded. One of the important benefits of a well-designed property tax or wealth tax would be to dampen rent-seeking and speculative activities, and channel funds to more productive investment.

Poor tax records and complex tax procedures complicate tax compliance and tax fairness analysis. Improving tax and customs administration, simplifying coding and regulation, and investing in technology to improve transparency can enhance compliance and increase the potential tax base.

This would require upfront investment in administrative infrastructure, but over a period, better tax administration would support a broader culture of tax compliance in addition to greater revenues. One way to improve transparency and accountability is the filing of income tax by every citizen, even if not everyone would actually pay tax – an approach that has been encouraged recently in India.

Second, take steps to control tax evasion, tax avoidance and illicit financial flows

In 2014 and 2015, illicit outflows from the Arab region outstripped the combined inflows of foreign direct investment and official development assistance (ESCWA, 2017b; IMF, 2016).

Trade mis-invoicing constituted a significant leakage, amounting to about 68% of cumulative illicit flows between 2011 and 2015. In addition to national tax reforms, a global standard for information exchange needs to be adopted to tackle illicit financial flows as well as cross-border tax evasion and tax avoidance.

Further reading

ESCWA (2017a) ‘Rethinking Fiscal Policy for the Arab Region’.

ESCWA (2017b) ‘The Arab Financing for Development Scorecard: Overall Results’.

IMF (2016) World Revenue Longitudinal Data.

Sarangi, Niranjan (2017) ‘Domestic Public Resources in the Arab Region: Where Do We Stand?’, ESCWA Working Paper.

Figure 1: