In a nutshell

Oil-producing countries with good financial institutions have dealt more successfully with the effects of volatility in oil prices than countries with poor financial institutions.

Institutions themselves may be adversely affected by large natural resource windfalls, for example, by making government policy less transparent.

‘Somewhat’ kleptocratic policy-makers benefit from opening their economy and reducing corruption levels, which suggests the potential for win-win options in various spheres of public policy.

Is the nature of public policy uniquely different in countries that are distinct by their large natural resource endowments? If so, how should we understand public policy in such countries?

Nowhere is the answer to these questions more critical than in the MENA region with its immense oil reserves. Here I try to provide the outlines of an answer.

First, we must understand that natural resources can act as both a blessing and a curse. The blessing aspect is straightforward: as a country’s windfall revenues expand, its ability to focus on public projects, education, health, poverty and other economic and social issues also expands, making trade-offs less painful. In effect, the country’s ‘production possibilities frontier’ expands. To a country with good institutions and an otherwise efficient economy, this is indeed a blessing.

Witness Norway, for example, though even here, challenges arise. But in this case, there are usually clear public policy solutions. For example, policy-makers must prevent infusion of too much liquidity that would cause inflation; or they must ensure consumption-smoothing and minimise large disruptions to expectations and thus investments, when faced with unexpected resource shocks. The emergence of sovereign wealth funds has been an effective public policy tool for addressing these types of issues in many resource-rich countries.

The difficulty arises – and this is the curse – because in many developing countries, including several in the MENA region, neither the economy nor the institutions are themselves immune to the adverse effects of a large revenue windfall from natural resources and especially oil.

This is especially true if institutions are weak, or economies are inefficient, to begin with. For example, research has shown that adverse economic outcomes of resource abundance occur with poor institutions, not well-developed institutions (see, for example, Boschini et al, 2007; Lane and Tornell, 1996; Mehlum et al, 2006; Robinson et al, 2006; and Tornell and Lane, 1999).

In one study, we find that oil-producing countries with good financial institutions have dealt more successfully with the effects of volatility in oil prices than countries with poor financial institutions. The difference is especially pronounced in the case of the post-2014 period, which has been characterised by massive and sustained drop in oil prices (Jarrett et al, 2016).

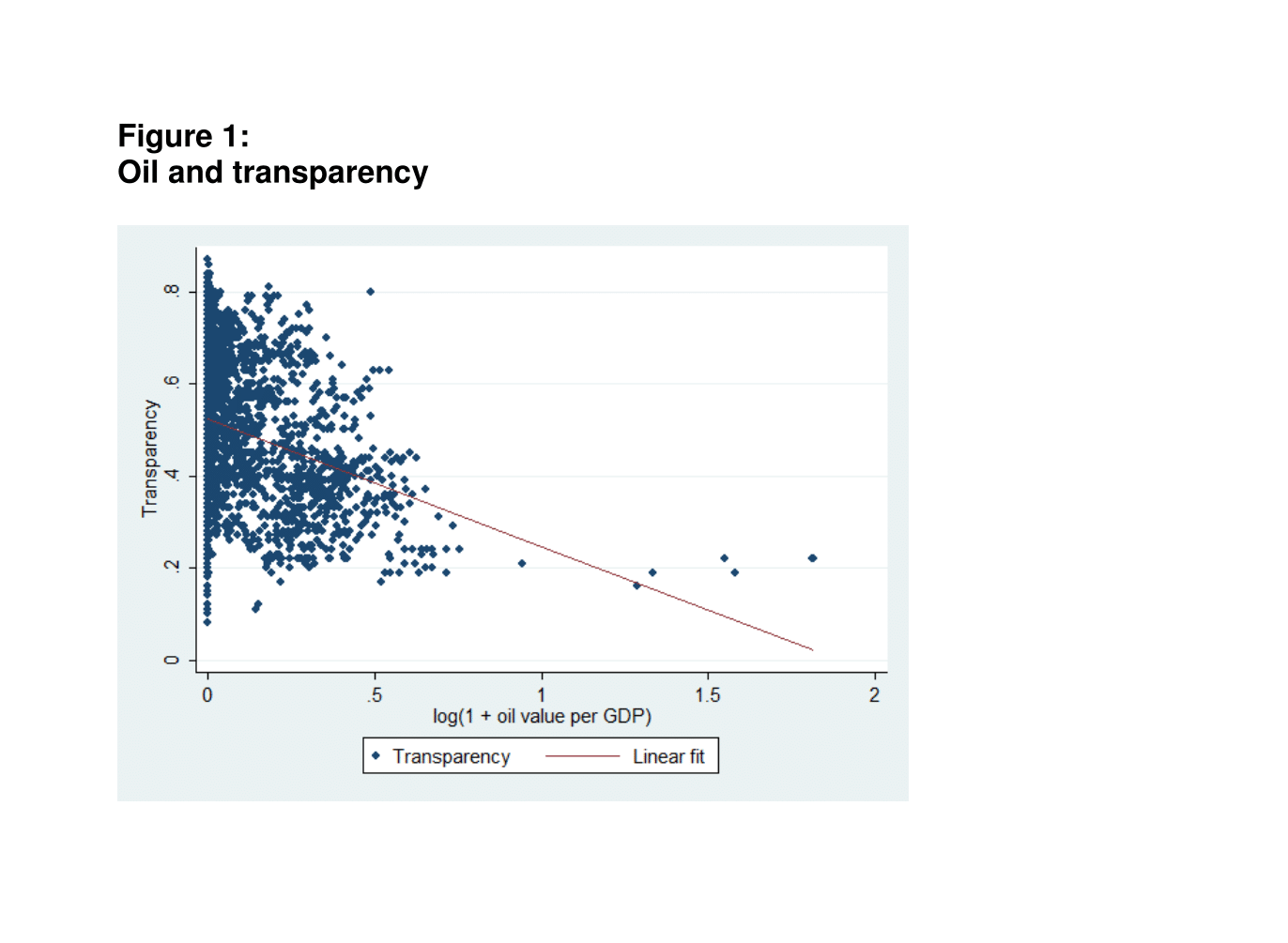

But institutions themselves may be adversely affected by large natural resource windfalls, for example, by making government policy less transparent (see Mohtadi et al, 2014; Ross, 2011; Williams, 2011; and Figure 1).

We show elsewhere how, in the case of oil, this reduced level of transparency also compromises the tax policies of the governments (Mohtadi et al, 2017). Our research suggests that in these circumstances, the task of public policy is more difficult. It is made even more complicated because policies must still be carried out by governments that are themselves imbedded in weak institutions or inefficient economies.

For example, kleptocracy is exacerbated with large resource windfalls, preventing officials from carrying out efficient public policy that is in the interest of all citizens – in the words of the late Nobel laureate, Leo Hurwicz (2007) ‘who will guard the guardians?’ Or market inefficiencies (for example, subsidies to favourite industries) produce interest groups that can influence public policy, making it difficult to fight ‘Dutch disease’, a common outcome of large resource shocks.

Even in these circumstances, however, there are good policy options. For example, in the case of kleptocracy we find that ‘somewhat kleptocratic’ policy-makers benefit from opening their economies and removing trade barriers – and in the process, they have incentives to reduce corruption (Mohtadi and Polasky, 2017). Since free trade increases overall welfare, we have an example of a win-win policy at work.

The fact remains that kleptocracy is not absolute and comes in different sizes and shapes. The indication that ‘somewhat’ kleptocratic policy-makers benefit from opening their economy and reducing corruption levels suggests that such win-win options might exist in other spheres of public policy.

One possible area might be economic policies that can accelerate the rate of growth. Elements within the government that favour rapid growth might be able to dominate those that lose out, owing to their ties to old or inefficient sectors.

As the examples above suggest, economists and reform-minded policy-makers within governments must be able to find ways in which practical and innovative policies can be carried out without invoking resistance from entrenched interests both within and outside the government. These examples illustrate that the set of such policies is not an ‘empty set’, to borrow a phrase from mathematicians.

Further reading

Boschini, A, Pettersson and J Roine (2007) ‘Resource Curse or Not: A Question of Appropriability’ Scandinavian Journal of Economics 109(3): 593–617.

Hurwicz, L (2007) ‘But Who Will Guard the Guardians?’, Nobel Prize Lecture.

Jarrett, U, K Mohaddes and H Mohtadi (2016) ‘Oil Price Volatility, Financial Institutions and Economic Growth’.

Lane, PR, and A Tornell (1996) ‘Power, Growth, and the Voracity Effect’, Journal of Economic Growth 1(2): 213-41.

Mehlum, H, K Moene and R Torvik (2006) ‘Institutions and the Resource Curse’ Economic Journal 116: 1-20.

Mohtadi, H, and S. Polasky (2017) ‘Can Economic Openness Reduce Corruption? Role Of Tax and Trade Policy’.

Mohtadi, H, M Ross and S Ruediger (2014) ‘Oil, Taxation and Transparency’.

Mohtadi, H, M Ross, S Ruediger and U Jarrett (2017) ‘Does Oil Hinder Transparency?’

Robinson, J.A, R Torvik and T Verdier (2006) ‘Political Foundations of the Resource Curse’, Journal of Development Economics 79: 447-68.

Ross, M (2011) ‘Mineral Wealth and Budget Transparency’.

Tornell, A, and PR Lane (1999) ‘The Voracity Effect’, American Economic Review 89(1): 22-46.

Williams, A (2011) ‘Shining a Light on the Resource Curse: An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship Between Natural Resources, Transparency, and Economic Growth’, World Development 39(4): 490-505.