In a nutshell

Measures of ‘inclusive growth’ for oil-exporting economies over the boom decade 2001-10 offer insights into debates about the resource curse.

Development outcomes need to be examined not just in terms of growth but also its quality, its sustainability and whether its benefits extend to wider society.

Achieving the imperative of converting oil revenues into sustained and inclusive growth faces a bumpy road ahead.

The idea of the resource curse associates high oil revenues in resource-rich countries with poor economic outcomes. The common yardstick for evaluating economic performance in such countries is GDP growth rates. But little attention has been devoted to whether the experience of economic development in oil-exporting countries in the MENA region has been inclusive and, if not, why not.

This is at odds with the fact that the relationship between growth and equity has a long tradition and deep roots in both economic analysis and development policy – an interest that has been revived in recent years with the social and political upheaval in several Arab countries.

Inclusive growth can be broadly conceived of as growth that benefits the widest social and economic groupings. Although there is not a universally agreed definition and making the concept operational has not met with consensual success, interest in ensuring that growth is inclusive has been on the rise.

The Asian Development Bank now features inclusive growth as a long-term strategic framework, and the African Development Bank too lists it as one of its development objectives. Various governments openly espouse its virtues and Thomas Piketty’s seminal work on wealth and income inequality in developed countries – Capital in the Twenty First Century – has further boosted academic and policy interest in the subject.

In the MENA region, such interest has been bolstered by the need to understand the economic performance of Arab countries in which widespread popular uprisings brought down autocratic regimes from Tunis to Yemen.

The fact that the decade before these uprisings coincided with unprecedentedly buoyant international oil prices and highly favourable incomes for oil-exporting countries has added an interesting dimension to habitual curiosity about the relationship between richness in oil endowments and general economic performance.

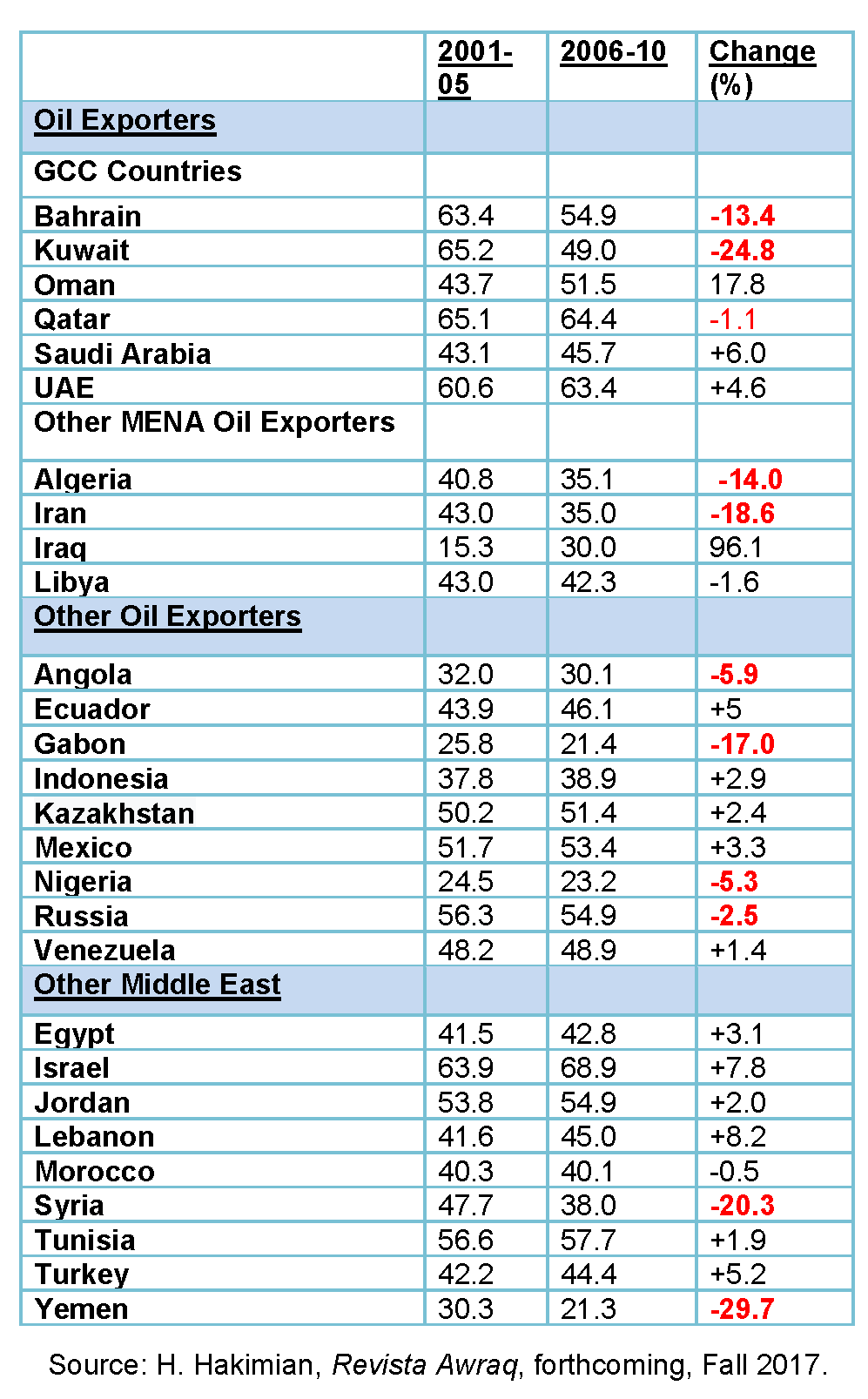

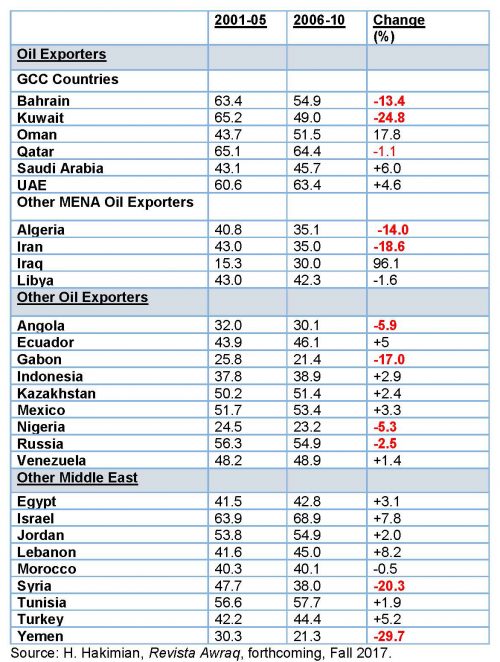

My research casts light on this issue by looking at the extent to which the recent growth experiences of the region’s oil-exporters may be considered to have been ‘inclusive’ (see summary table below).

The study constructs a single composite index for measuring ‘inclusive growth’ for each country based on 14 indicators related to broad economic, social, political and environmental dimensions of growth and development. It uses a comparative approach to rank 153 countries for which consistent and reliable data are available for the two five-year periods of 2001-05 and 2006-10 (the decade prior to the uprisings).

The results for oil-exporting economies of the MENA region offer new insights into debates about the resource curse.

First, the small Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states – Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and United Arab Emirates – have the highest inclusive growth indices. Their inclusive growth indices exceed 60 on a scale of 0 to 100, putting them on a par with Israel in both periods and in the top median globally.

By contrast, Saudi Arabia, followed by Oman, appear to be least inclusive in both periods with an inclusive growth index that is on a par with other more populous oil-exporting countries, such as Iran and Algeria. With an inclusive growth score of 40-plus, these countries appear in the lower median of all countries.

Examining performance over time reveals further insights. Here, the smaller GCC oil-exporting states indicate a marked deterioration in their inclusive growth performance. Bahrain, Kuwait and, to a lesser extent, Qatar show a decline in their index over the two periods. This pattern also holds for other, larger MENA oil-exporting countries: Iran, Algeria and, to a lesser extent, Libya exhibit a similar and significant deterioration in their indices.

Beyond the MENA region, the experience of oil-exporting countries in Africa also shows a deteriorating trend of inclusivity over this period: Angola, Gabon and Nigeria (all three OPEC members) seem to have followed the experience of the small GCC states in that they exhibit a deterioration of their record over time.

The picture outside the MENA region and Africa is somewhat mixed, with Russia among the major oil-exporting countries also suffering a deterioration, while Ecuador, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Mexico and Venezuela show only modest improvements. As would be expected, this is in sharp contrast with Norway – another oil-exporting country – which is ranked consistently among the world’s top five nations in inclusivity.

Among non-oil-exporting countries in the MENA region, the deteriorating experiences of Syria and Yemen stand out (the latter is ranked 152 out of 153 countries in the 2006-10 period). The biggest improvement is recorded by Iraq between the two periods (almost doubling), indicating the difficulties and challenges of the early years of the war period after 2003.

Further analysis shows that in general, the low or deteriorating inclusive growth indices across MENA oil-exporting countries is explained by below par performances for unemployment in general and youth unemployment in particular. For example, Saudi Arabia ranks last among 153 countries for youth unemployment during 2006-10. Other development dimensions, such as gender and the environment, do not help the country’s overall growth inclusivity either, while data on poverty and inequality are unfortunately patchy.

My results underscore one overriding economic lesson of a decade that saw an unprecedented surge in oil prices (2001-10): the need to examine outcomes not just in terms of growth but also the quality of growth, its sustainability as well as the degree to which its benefits may extend to wider society.

Given the generally lacklustre performance of these countries across a wide range of dimensions (except for the smaller GCC states), it would require a concerted effort to improve their track record on inclusive growth. A focus on one or two selective dimensions will not be sufficient to improve their comparative ranks.

But as is widely known, labour market challenges – job creation and the reduction of unemployment, especially among young people – remain key in this process and the principal route to achieving inclusive growth for them. This is despite the fact that achieving the imperative of converting oil revenues into sustained and inclusive growth faces a bumpy road ahead.

Estimated ‘Inclusive Growth’ Scores, 2001-05 and 2006-10, Normalized Ranks (min=0; max=100)