In a nutshell

The direct effect of foreign direct investment is to increase carbon emissions in MENA economies, although the precise relationship with pollution depends on a country’s characteristics, including human capital, and institutional quality and governance.

Foreign direct investment leads to pollution in MENA economies with a less educated labour force and an unfavourable institutional environment; it lowers pollution in countries with more educated workers and a favourable institutional environment.

Policies aiming to improve human capital and the institutional environment may be expected to enrich not only the economic benefits of foreign direct investment in terms of growth, but also to mitigate its negative environmental effects.

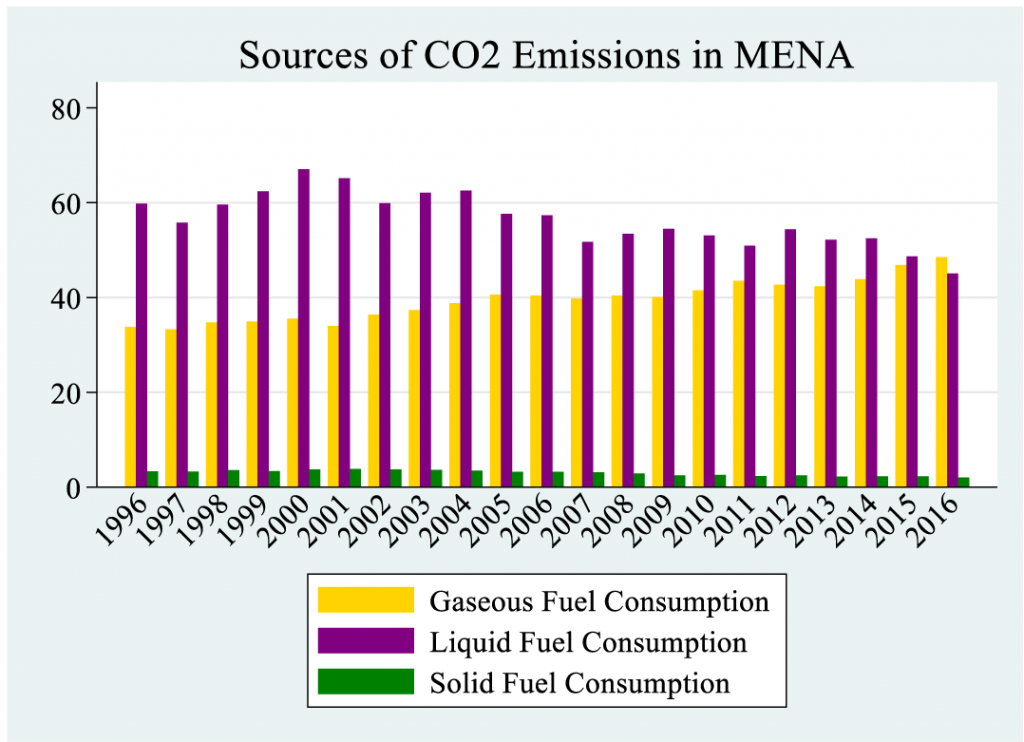

Economies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) face serious environmental vulnerabilities, including air pollution, loss of biodiversity and inadequate waste management. In addition, the extensive use of gaseous and liquid fuel (as a percentage of total consumption – see Figure 1) and non-renewable energy resources in production tends to draw attention to environmental concerns by increasing emissions levels.

High emissions may impede MENA economies from achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to promote the green economy. ‘Greening’ is related to the low-carbon energy transitions aiming for access to renewable energy sources, reducing poverty and creating jobs (Siciliano et al, 2021).

A recent report from the World Bank (Heger et al, 2022) remarks that a green, resilient and inclusive development (GRID) trajectory will provide sustainable growth in MENA economies. Accordingly, GRID growth trajectory is expected to lower emissions, mitigate environmental degradation, support the sustainability of the environment and thus enable MENA economies to achieve the SDGs.

Figure 1: Sources of carbon emissions in MENA

Emissions levels can be affected by income per capita, energy consumption, technological innovation, trade openness, urbanisation and inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI). Among these, the last, FDI, is one of the most important.

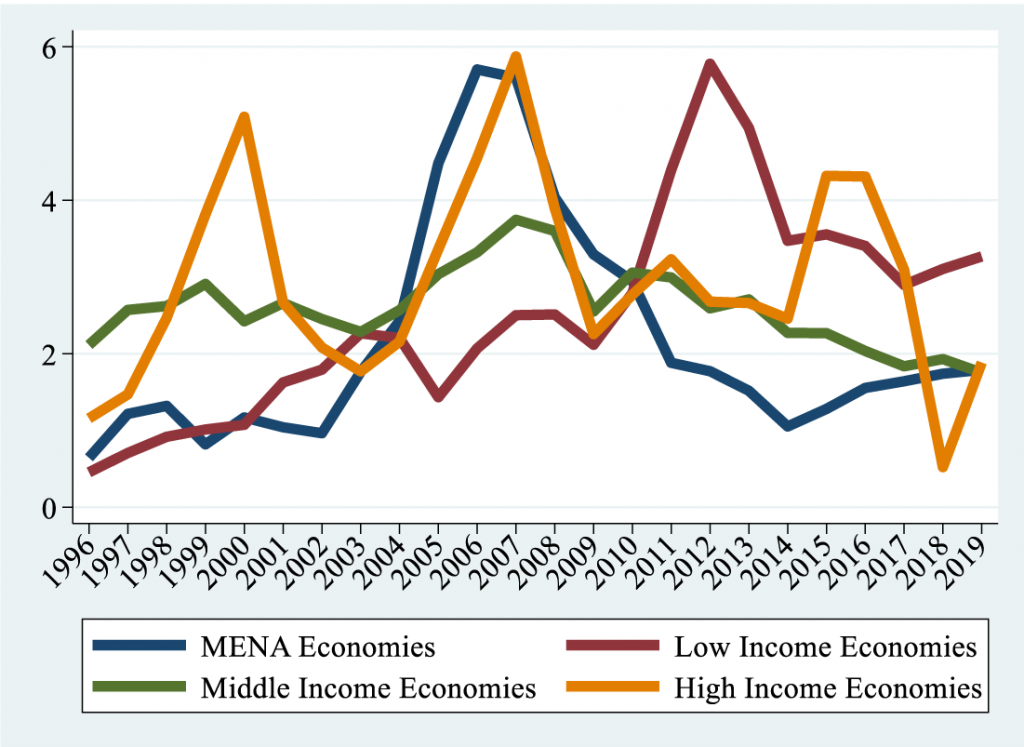

Conventionally, FDI provides many benefits including efficient capital allocation, access to financial markets and new technology, increasing total factor productivity and growth. Figure 2 represents the evolution of FDI in low-, middle- and high-income economies along with MENA. FDI inflows to MENA economies tend to be much lower than in other country groupings.

Figure 2: Evolution of FDI inflows

The impact of FDI on the environment is one of the important policy concerns for the authorities. The relationship between FDI and pollution can be explained with pollution haven or halo arguments.

The pollution haven argument maintains that FDI linkages may allow the movement of pollution-intensive economic activities to countries with lax environmental restrictions and regulations. The pollution halo argument, on the other hand, suggests that international firms with high environmental quality may bring sophisticated, energy-efficient, environmentally cleaner technologies to host economies along with better environmental management systems.

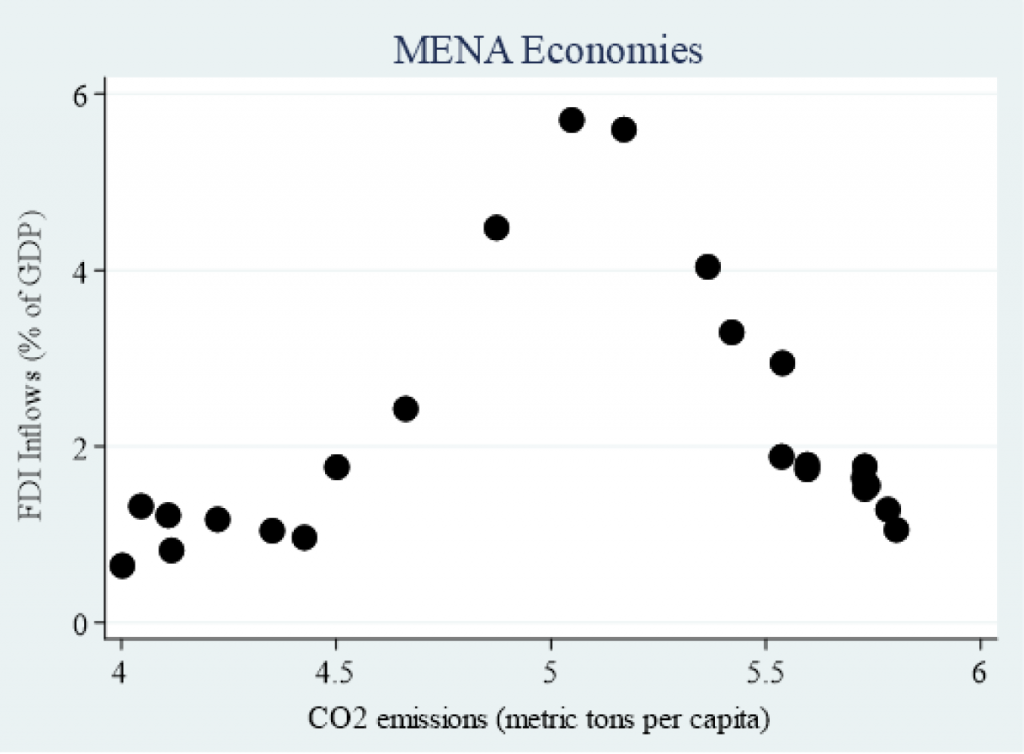

Figure 3 shows the scatter plot of FDI and carbon emissions. There is a positive association between FDI and emissions up to a certain threshold level and then this relation reverses in MENA.

Figure 3: FDI inflows and carbon emissions

The prevailing characteristics of a country, including its human capital and governance, may affect the impact of FDI on pollution with different transmission mechanisms. For example, a more educated labour force demands a cleaner environment, encourages the use of renewable energy products, promotes energy efficiency and tends to adopt better environmental regulation as well as greener technology.

On the other hand, economies with well-established rules, norms and regulations allow them to implement environmental protection policies. In this context, we can maintain that the positive association between FDI and emissions in Figure 3 may belong to economies with weak country characteristics. On the flip side, the negative association between FDI and emissions in Figure 3 may be related with the economies with better country characteristics.

Pollution haven or halo?

Our study finds that the direct effect of FDI is to increase emissions in MENA. But it may be misleading to assume that the sensitivity of FDI to pollution is the same in economies with weak and better country characteristics. Better characteristics – that is a more educated labour force and a more favourable institutional environment – can attract higher FDI.

In this context, we can maintain that prevailing country characteristics may affect the relationship between FDI and pollution. We find that prevailing country characteristics provide a threshold for the effect of FDI on emissions. This can imply that the relationship between FDI and emissions can change with the level of country characteristics.

Our results suggest that FDI leads to higher emissions in economies with weak country characteristics, including a less educated labour force and an unfavourable institutional environment. On the other hand, FDI lowers emissions in countries with strong country characteristics containing a better educated labour force and a favourable institutional environment.

Our empirical findings indicate that the pollution haven argument holds economies with weak country characteristics while the pollution halo argument holds in the case of economies with better country characteristics. This outcome appears to be hold in both oil-exporting and oil-importing MENA economies.

Our results suggest that policies aiming to improve human capital and the institutional environment may be expected to enrich not only the economic benefits of FDI in terms of growth but also to mitigate its negative environmental effects. Investing in human capital also eases the employment of environment-friendly technologies and increases environmental awareness.

Consistent with an argument maintaining that a good institutional environment is closely associated with the implementation of better environmental protection policies, improvement in institutional quality and governance is expected to reduce both emissions and the degradational effect of FDI.

Based on our empirical findings, policies aiming to promote energy efficiency, energy conservation and emissions-diminishing technologies may alleviate the pollution. These policies may lead countries to succeed in achieving goals that promote green economy.

GRID growth trajectory can reduce emissions, alleviate environmental degradation, encourage environmental sustainability, mitigate poverty, provide job creation and thus allow MENA economies to achieve the SDGs.

Environmental management systems aiming to reduce emissions may require institutional and regulatory reforms, green investment, better governance, regional cooperation and participation of all stakeholders. Xing and Kolstad (2002) suggest the necessity of cooperative solutions to overcome pollution since the environmental policy gap leads the movement of polluting production activities to economies with lax environmental regulations.

The World Bank report (Heger et al, 2022) proposes a ‘4 I’s’ rule for MENA economies including ‘Inform stakeholders, provide Incentives, strengthen Institutions, and Invest in abatement options’ to solve environmental problem. All these may be considered as key factors to overcome the problem of environmental degradation in MENA.

Further reading

Abdouli, M, and S Hammami (2017) ‘Investigating the causality links between environmental quality, foreign direct investment and economic growth in MENA countries’, International Business Review 26(2): 264-78.

Heger, Martin Philipp, L Vashold, A Palacios, M Alahmadi, M Bromhead and M Acerbi (2022) ‘Blue Skies, Blue Seas Air Pollution, Marine Plastics, and Coastal Erosion in the Middle East and North Africa.’ Middle East and North Africa Development Report, World Bank.

Siciliano, G, L Wallbott, F Urban, AN Dang and M Lederer (2021) ‘Low-carbon energy, sustainable development, and justice: towards a just energy transition for the society and the environment’, Sustainable Development 29: 1049-61.

Taşdemir, F, and S Ekmen-Özçelik (2022) ‘Do Human Capital and Governance Thresholds Matter for the Environmental Impact of FDI? The Evidence from MENA Countries’, ERF Working Paper No. 1608.

Xing, Y, and CD Kolstad (2002) ‘Do lax environmental regulations attract foreign investment?’, Environmental and Resource Economics 21(1): 1-22.