In a nutshell

Key elements of public health resilience (the ability of healthcare systems to absorb the onslaught of health emergencies) – namely surveillance and absorptive capacity – were inadequate in the MENA region when Covid-19 hit.

Some countries adapted and reacted quickly to the pandemic and managed impressive responses both on the policy and pandemic containment fronts; unfortunately, many other countries in the region did not.

Stressed healthcare systems combined with global economic factors – such as fluctuations in commodity prices, particularly oil – to produce an uneven economic recovery for the region and a tenuous outlook.

The Covid-19 pandemic challenged healthcare systems and societies the world over. Even some of the best-endowed healthcare systems lacked the leadership needed to contain the outbreak. Moreover, successive mutations of the coronavirus continue to threaten global public healthcare systems and, in turn, global economic prospects.

Amid the current scientific uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic, one thing is certain: core public health functions such as surveillance, disease prevention and preparedness have never been more important than they are today. In addition, an open and data-driven rapport between the state and its citizens, which allows governments to take rapid and targeted actions and allow people to make the best decisions to protect themselves from contagion, has never been more apparent.

All of these factors are necessary for successful pandemic control. Yet on the eve of the pandemic, none were in place in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Before the Arab Spring, countries in the region pursued an economic development model that relied on public sector expenditures and public employment. Since then, reforms in MENA have advanced slowly, resulting in a truncated transition toward market economies characterised by fiscal myopia.

As argued in the World Bank’s April 2021 MENA Economic Update, public spending priorities in MENA have continued to favour public employment rather than investments in core public goods, such as building resilient public healthcare systems. Consequently, on the eve of the pandemic, public healthcare systems in MENA tended to be underfunded, particularly in middle-income countries, even though the size of the public sector had grown as a share of GDP.

Low expenditures on public health relative to the public sector’s wage bill seem to have shifted the financial burden of healthcare toward individuals, as evidenced by disproportionately high out-of-pocket spending on medical care. As important, transparent disease surveillance practices were overlooked, while reserve health service capacity was comparatively limited.

In other words, key components of pandemic response – namely, surveillance and absorptive capacity – were inadequate when Covid-19 hit, even though the economic footprint of the state in the economy had increased since 2009.

Since 2009, most MENA countries have also experienced demographic and epidemiological changes that contributed to their healthcare systems being ill-prepared to handle health emergencies. The demographic profile of MENA’s population was shaped by atypically high fertility rates. The associated increases in dependency ratios – the shares of children and older people in the population – exacerbated macroeconomic imbalances in the form of current account deficits.

Perhaps more importantly, high fertility rates produced a young population. Statistically, it created the illusion of a healthy population because children are less susceptible to non-communicable diseases than adults.

Meanwhile, truncated epidemiological transitions resulted in abnormally high burdens of diseases in the region. Several countries recorded high deaths per capita from both communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), while all MENA countries experienced either high death rates due to NCDs relative to other countries at the same level of development or atypically high increases in the burden (deaths) of NCDs.

The empirical evidence presented in Gatti et al (2021) also shows that MENA’s public health authorities were painting rosy pictures of their public healthcare systems on the eve of the pandemic. Their self-reported preparedness indicators were systematically more optimistic than that of countries with similar levels of development, while objective indicators showed MENA countries underperforming their peers, with Jordan being an important exception.

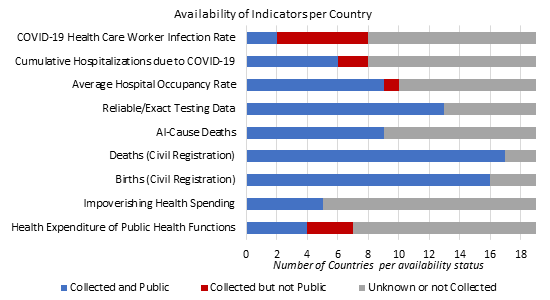

The lack of data and data use probably limited a realistic assessment of healthcare systems’ preparedness. To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the availability of nine indicators of key aspects of public health in 19 MENA countries. About half of the time, the data are found to be publicly available. Some types of data were collected, yet not publicly available. And in many cases, it was not possible to ascertain whether the data were available. This shows that even if data are collected, they are often difficult to find and access.

Figure 1: Availability of public health data across MENA countries

Source: Gatti et al (2021)

The advent of Covid-19 put MENA healthcare systems under duress, further depleting limited functional and reserve capacities, exacerbating existing challenges and revealing vulnerabilities that could no longer be compensated for. Thus, the pandemic was a stress test of the resilience of the healthcare system, which highlighted the importance of meeting pre-existing unmet healthcare needs.

Moreover, it provided a new understanding of underlying weaknesses that predisposes countries to future and certain health risks. Excess mortality – the difference between the total number of deaths (from all causes) during the pandemic and the pre-pandemic number of deaths – is among the important measures of a country’s resilience and the simplest way to compensate for insufficient case detection. It postulates, reasonably, that the excess deaths are either directly from Covid-19 or the result of health service disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Yet these data largely do not exist within MENA, in part owing to baseline shortcomings such as limited death registrations, data aggregation or data reporting. Some data, however, are indicative for the region: for example, excess deaths reported in Egypt in 2020 were 13 times greater than officially counted Covid-19 deaths (Karlinsky and Kobak, 2021).

As if the death count were not enough, the last two years have shown that economic performance depends to a significant extent on pandemic control. Stressed healthcare systems have combined with global economic factors – such as fluctuations in commodity prices, particularly oil – to produce an uneven economic recovery for the region and a tenuous outlook.

The region is forecast to grow by 2.8% in 2021 and 4.2% in 2022. But these averages mask important differences across countries. Each economy’s performance depends heavily on its exposure to commodity price fluctuations and how well it managed the pandemic.

More importantly, most countries might not rebound fast enough to reach their pre-pandemic levels of GDP per capita until 2022, let alone the levels predicted before the pandemic. Downside risks abound – including the possibility of a prolonged pandemic, especially in the middle-income and low-income countries in MENA, where vaccinations are lagging.

In sum, the crisis caught most MENA countries with underfinanced, imbalanced and ill-prepared healthcare systems. Yet MENA public health authorities reported overly optimistic assessments of their healthcare systems’ resilience.

But there is a silver lining in two respects. First, some countries adapted and reacted quickly to the pandemic and managed impressive responses both on the policy and pandemic containment fronts. The best examples of substantial investments in public health response are concentrated in the high-income countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Unfortunately, many other countries in the region were unable to make the necessary emergency investments in their public healthcare systems, including with respect to procuring testing, protective gear and eventually vaccines.

Second, the use of data – a necessary ingredient – became critical for public health policy-making. The advances made in this regard can be built on for deeper reforms and building resilient healthcare systems to handle future public health calamities that will arise due to conflict, natural disasters associated with climate change and, yes, future epidemics.

Together with a strong focus on building core public health functions, embracing and leveraging the power of data openness can help to promote the region’s recovery and build truly resilient healthcare systems.

Further reading

Gatti, Roberta; Lederman, Daniel; Fan, Rachel Yuting; Hatefi, Arian; Nguyen, Ha; Sautmann, Anja; Sax, Joseph Martin; Wood, Christina (2021) ‘Overconfident: How Economic and Health Fault Lines Left the Middle East and North Africa Ill-Prepared to Face COVID-19’, Middle East and North Africa Economic Update (October), World Bank.

Karlinsky, Ariel, and Dmitry Kobak, 2021 ‘Tracking excess mortality across countries during the COVID-19 pandemic with the World Mortality Dataset’, eLife 10: e69336.