In a nutshell

Labour market flexibility is negatively associated with the unemployment rate and does not necessarily lead to increased public expenditure on social protection; indeed, wage flexibility and stronger links between pay and productivity reduce social spending.

Competition, both domestic and foreign, can increase wage flexibility and the link between pay and productivity; greater competition requires more private sector participation in the economy and support of entrepreneurship.

Having an educated and well trained labour force, greater gender equality and labour mobility are key to achieving labour market flexibility.

Labour is one of the main factors of production, which include land, capital, entrepreneurship and technology. Firms demand for labour is driven by the wage rate, which reflects labour productivity: more productive labour should get higher wage rates. Labour supply is driven by workers’ decisions to offer their labour services: workers’ supply decision is driven by the wage rate they get. The interaction of labour demand and supply determines the equilibrium wage rate and quantity of labour.

Labour market flexibility is important for the operation of the labour market. Flexibility allows the labour market to reach equilibrium. If the economy is hit by a recession, which slows down demand for firms’ products, firms may respond by reducing the demand for the factors of production. Labour is typically the first factor of production to be reduced.

Flexible or deregulated labour markets allow firms to respond fast to changing economic conditions. Regulated labour markets, in contrast, impose laws and regulations, which protect workers. These include the firing of workers, the minimum wage rate, workers compensation and benefits, and work hours. Political organisations contribute to the regulation of labour markets: Labour unions may undertake collective bargaining to protect workers.

Flexible labour markets allow the efficient use and allocation of labour through labour services pricing. Through wage rate adjustments, flexible labour markets induce labour competition and productivity, and reduce unemployment.

But the efficient allocation of labour resources may come at the expense of the wellbeing of labour. Firing workers results in income losses and hurts them economically, psychologically and socially.

Government intervention helps protect the wellbeing of workers. Government provides what is known as social protection, which extends beyond the risk of unemployment.

Social protection comprises policies and programme that protect families against through income transfers. It also includes social insurance programmes, which protect workers from income loss associated with the risks of unemployment, illness, accidents, disability or old age (Ganßmann, 2000; Asher and Zen, 2015).

What determines labour market flexibility?

The determinants of labour market flexibility have not attracted much attention in research in labour economics, to the best of our knowledge. What is known though is that political ideology and organisation determine market flexibility. Labour unions and socialist governments through collective bargaining and employment protection legislations reduce labour market flexibility.

Population demographic composition may affect labour market flexibility. In the presence of a relatively aging population, motivating workers through wage flexibility and linking pay to productivity may not be very effective in raising productivity. Encouraging migration of young labour is perhaps a better strategy to increase production and productivity.

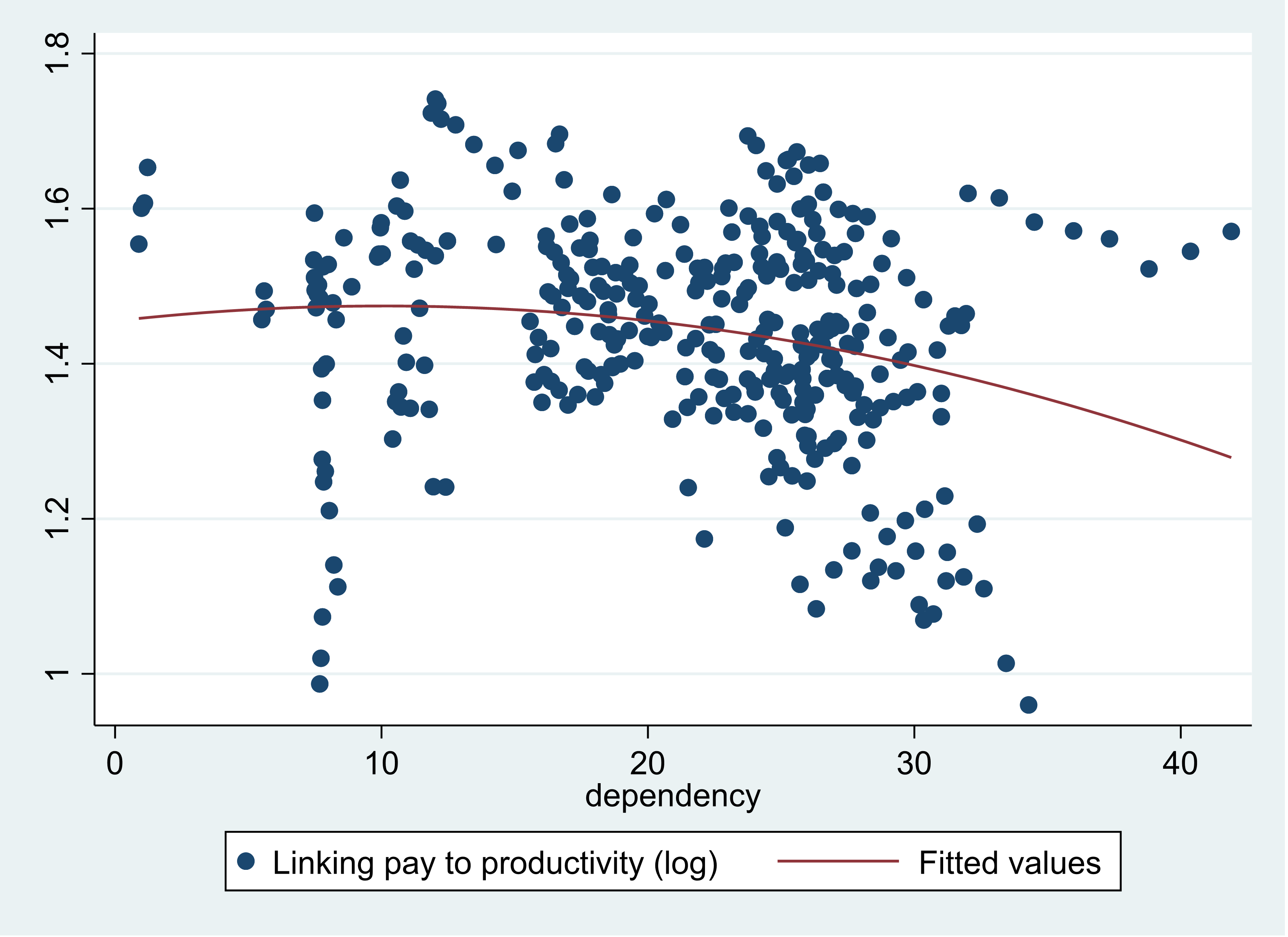

Statistical analysis shows that the increase in the share of the elderly population weakens the link of pay to productivity – see Figure 1 .

Figure 1: Dependency and linking pay to productivity

In contrast to the negative effect of socialist political ideology and organisation, and an elderly population, economic growth increases labour market flexibility. To speed up economic growth, an efficient allocation of resources, including labour, is required. Rewarding labour motivates and increases productivity.

The pursuit of economic growth as a goal typically requires more private investment (domestic and foreign) in the economy. Private sector participation requires liberal economic environment, including a flexible labour market that allows investors to motivate productivity through higher wages, easily hire and fire, and decide on flexible working hours.

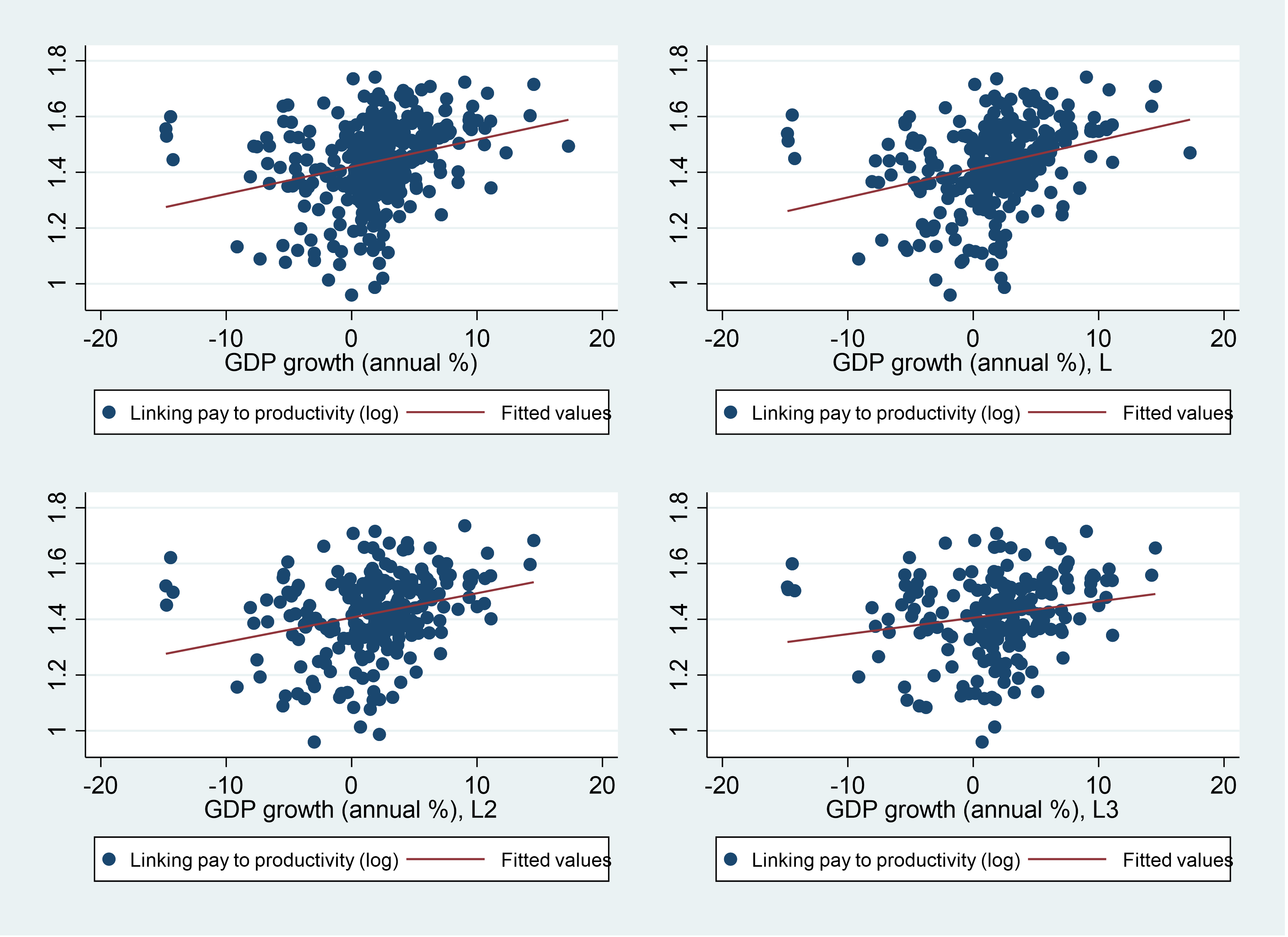

Figure 2 shows the relationship between annual real GDP growth rate and linking pay to productivity. Because of the problem of reverse causality, that is, linking pay to productivity influencing the growth rate as one would normally expect, we use lagged growth rates as well. The graphs show a positive relationship between growth rates and linking pay to productivity.

Figure 2: GDP growth rate and linking pay to productivity

What determines social protection?

Social protection is a component of government expenditures. To understand what determines it, it is important to understand the determinants of government expenditures. Government expenditures, which include spending on public goods, are explained by supply and demand factors (see Lindauer and Velenchik, 1992).

The demand for public goods is explained by the growth in income: spending on public goods increases with the increase in GDP (per capita). It also increases with the degree of economic development: as the economy becomes more industrialised and urbanised, the need to invest in human capital increases, and government spends more on health, education, and infrastructure. On the supply side, government expenditures more broadly (than public spending) are determined by the availability of government resources.

Although income determines the demand for public goods, there is no market for public goods unlike private goods. To garner support during elections, politicians respond to voters’ preferences and increase the supply of public goods. In addition, in seeking to increase their power, public administrators (bureaucrats) increase the supply of public goods.

While the determinants of government expenditures and public goods are relevant to social protection, the relevance is not straightforward. Although spending on public goods increases with income, a higher per capita income may reduce the need for social protection. The degree of economic development, measured by per capita income, increases investment in health and education, and therefore reduces the risks of unemployment, illness, and disability.

Globalisation influences social protection. As the economy develops further and becomes more integrated into the world economy, social protection may be less needed if the economy is competitive, exports more goods and services, and attracts more foreign investment. As production increases and the economy grows, more jobs are created and employment increases. The demand for social protection may therefore decrease. If the economy is not competitive enough, the demand for social protection may increase though.

Does labour market flexibility influence social protection expenditures?

In addition to the above determinants, social protection may be determined by labour market flexibility. Labour market flexibility may increase the firing of workers and the percentage of unemployed workers in the labour force or the unemployment rate. Accordingly, the demand for unemployment benefits and social protection may increase.

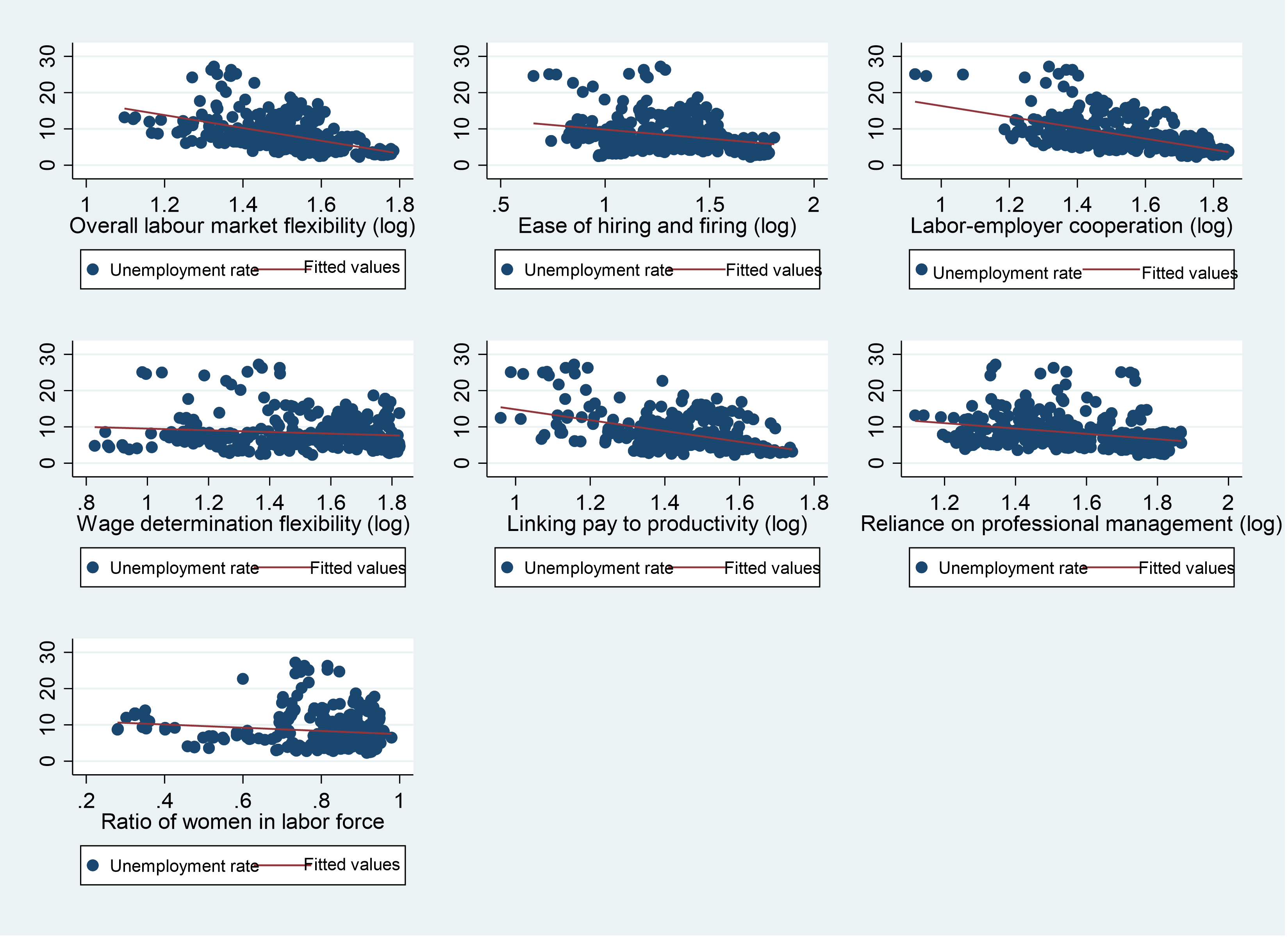

Clearly the relationship between labour market flexibility and social protection hinges on the unemployment rate and unemployment benefits. Using the panel data of Mina (2020; 2021), analysis shows there is a negative relationship between the labour market flexibility and the ILO-modelled unemployment rate (Figure 3). This casual evidence suggests that claims that labour market flexibility increases unemployment rate and jeopardises the social security of labour seems exaggerated.

Figure 3: LMF and the unemployment rate

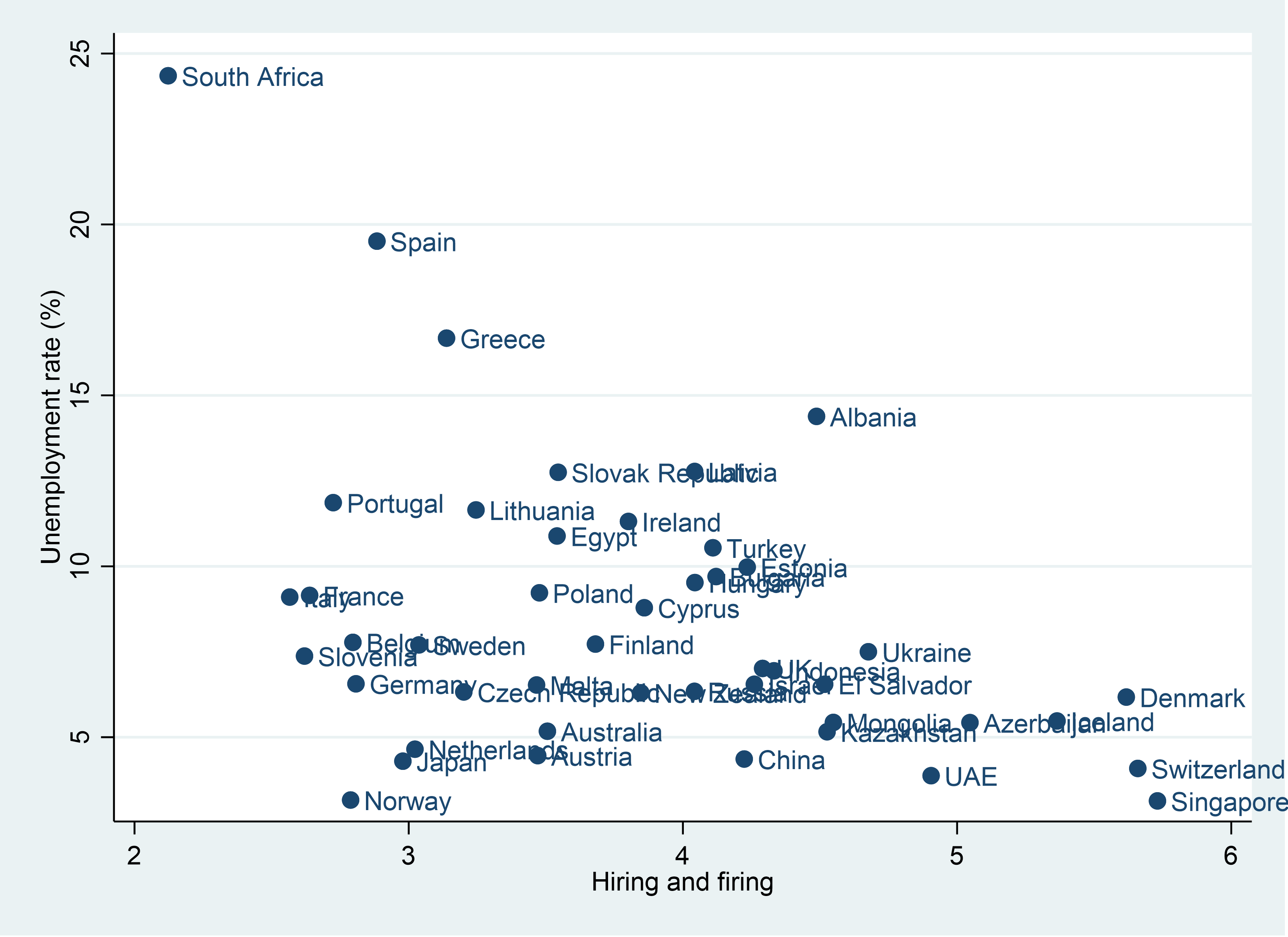

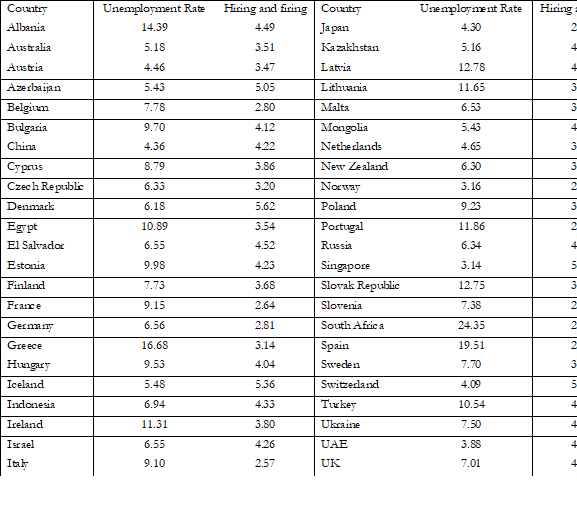

Figure 4 shows a negative relationship between the unemployment rate and the ease of hiring and firing for the sample countries. Each point on the graph shows average unemployment rate and hiring and firing scores for a specific country. On the one extreme lies South Africa with the highest sample unemployment rate of 24.4% and the lowest hiring and firing score of 2.12. On the other extreme lies Singapore with the lowest unemployment rate of 3.14 and the highest hiring and firing score of 5.73.

Figure 4: Unemployment rate and the ease of hiring and firing

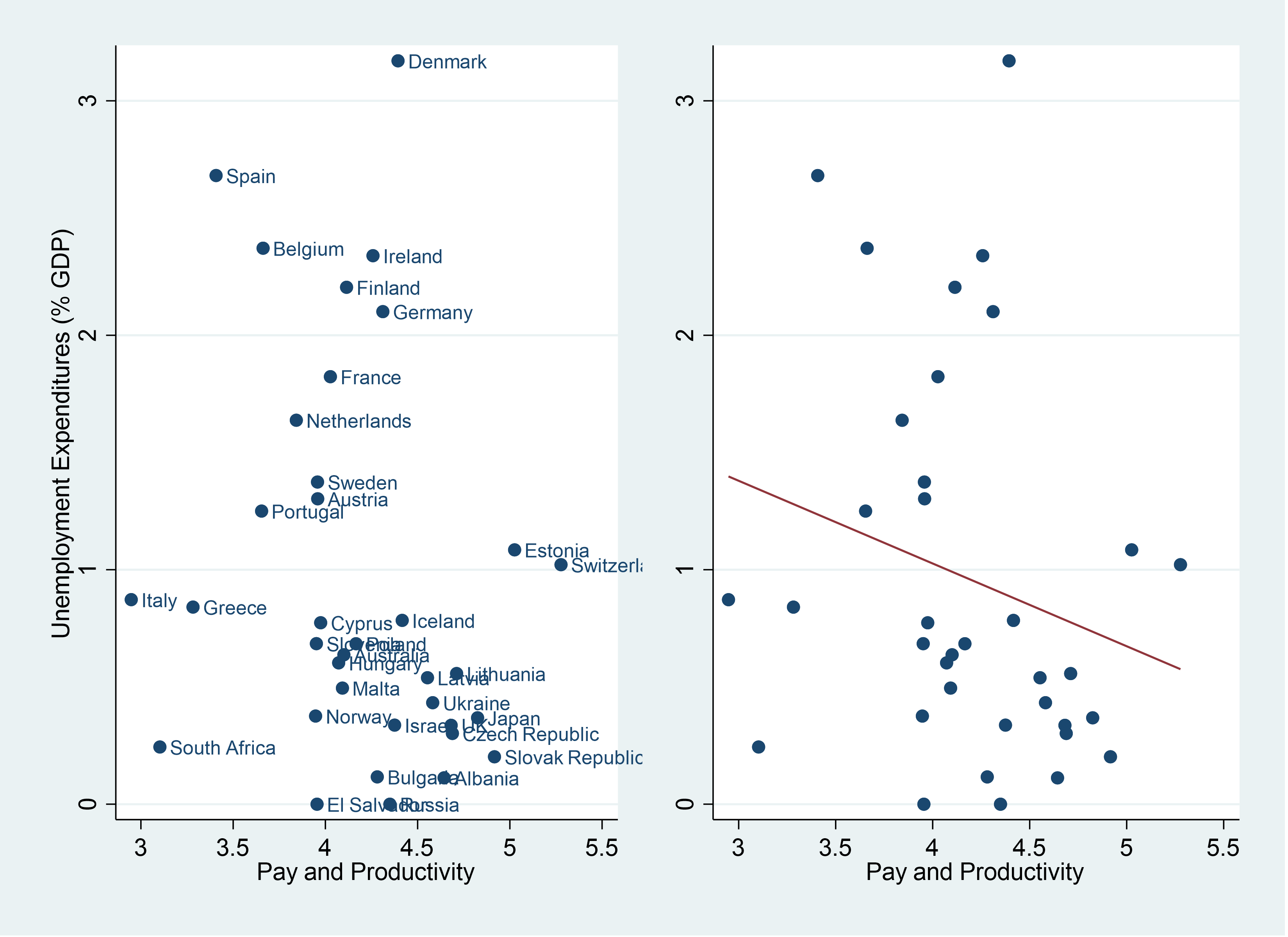

Figure 5 shows the relationship between unemployment expenditures (% GDP) – a broader measure of unemployment benefits – and linking pay to productivity. The right panel highlights the negative relationship between the two, while the left panel specifies the country averages. This indicator suggests that labour market flexibility does not necessarily impose a burden on government expenditures.

Figure 5: Unemployment expenditures and linking pay to productivity

Having provided evidence on the relationship between labour market flexibility, the unemployment rate and unemployment expenditures, we can now shed light on the influence of labour market flexibility on social protection expenditures, building on Mina (2020; 2021).

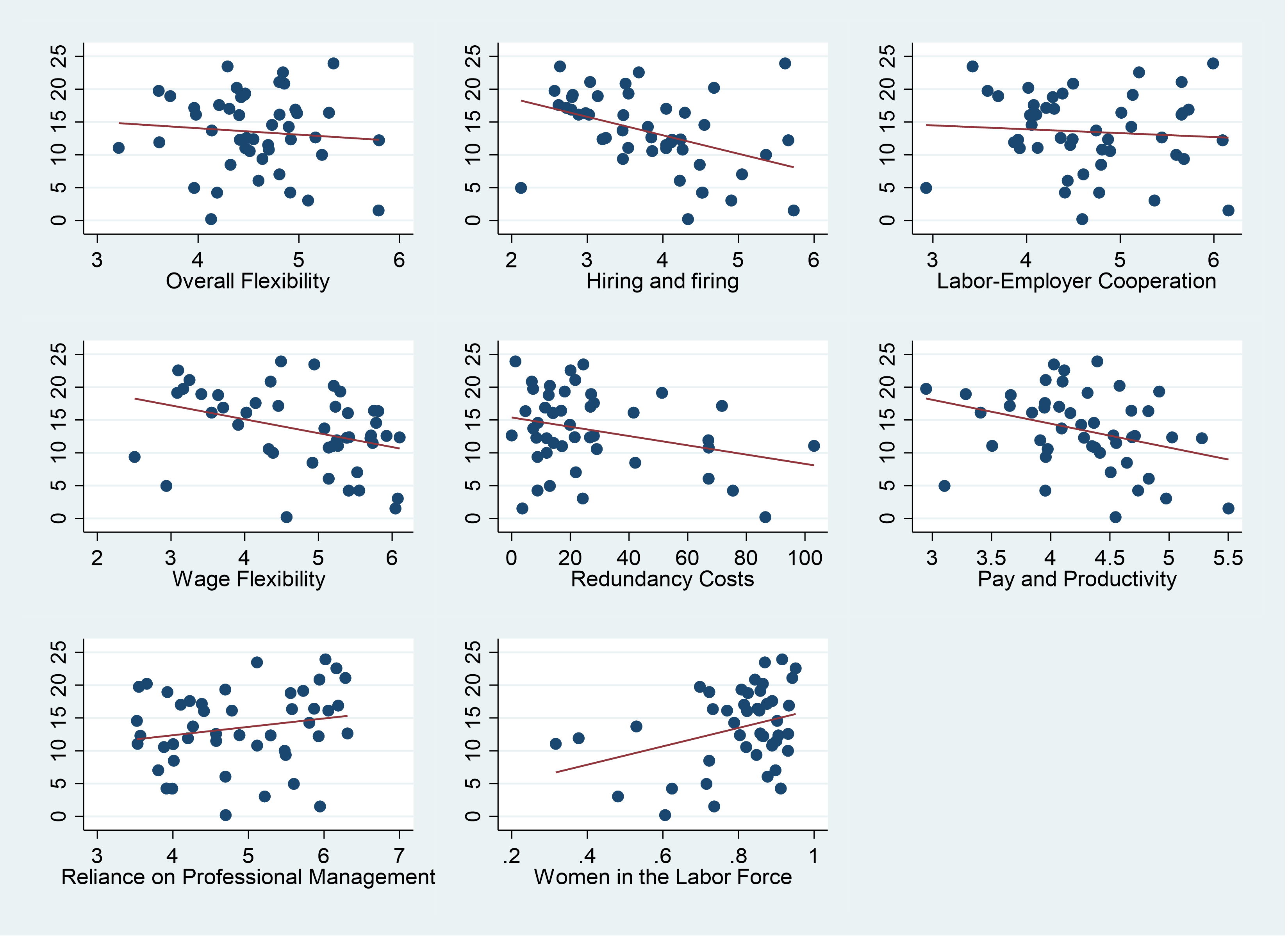

Labour market flexibility is measured using the labour efficiency pillar indicators of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report. These indicators include overall labour market flexibility, the ease of hiring and firing practices, employer-employer cooperation, wage determination flexibility, redundancy costs, linking pay and productivity, reliance on professional management, and the participation of women in the labour force. Social protection expenditures data are obtained from the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics.

Figure 6 shows that labour market flexibility reduces social protection expenditures. This relationship holds for all but two indicators – reliance on professional management and the percentage of women in the labour force.

Figure 6: Social protection expenditures and LMF

Notes: Social protection expenditures (% GDP) is on the Y-axis.

Econometric analysis of the relationship between labour market flexibility and social protection expenditures is undertaken in Mina (2021). Empirical evidence shows that wage determination flexibility, linking pay to productivity, and redundancy costs reduce social protection expenditures. A 1% improvement in wage flexibility and linking pay to productivity reduces social protection expenditures between 2.7-2.9 and 5.0-5.5 percentage points, respectively. Mina (2020) confirms the negative influence of linking pay to productivity.

Appendix A: Unemployment rate and the ease of hiring and firing (period average)

Conclusion

In conclusion, this column argues that labour market flexibility need not be a concern for unemployment and social protection expenditures. The analysis shows that flexibility is negatively associated with the unemployment rate, unemployment expenditures and social protection expenditures. Econometric analysis shows that enhancing labour efficiency through wage flexibility and linking pay to productivity reduces the burden on the fiscal budget.

Further reading

Asher, MG, F and Zen F (2015) Social protection in ASEAN: Challenges and initiatives for post-2015 vision’, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper No. 15-13.

Ganßmann, H (2000) ‘Labour market flexibility, social protection and unemployment’, European Societies 2(3): 243-269.

Lindauer, DL, and AD Velenchik (1992) ‘Government spending in developing countries: Trends, causes, and consequences’, World Bank Research Observer 7(1): 59-78.

Mina, W (2021) ‘Do Labor Market Flexibility and Efficiency Increase Social Protection Expenditures?’, Applied Economics.

Mina, W (2020) ‘Social Protection Expenditures and Performance-Pay’, Review of Development Finance 10(2): 38-61.