In a nutshell

Despite a recovery in economic growth, employment rates in Egypt have not recovered since they began declining in 2011.

The overall quality of jobs has also continued to decline, as informalisation has continued apace and real wages have declined.

Despite the generally negative trends of greater job informality and lower real wages, a few indicators of job quality have shown improvement, namely those to do with the job security of informal workers.

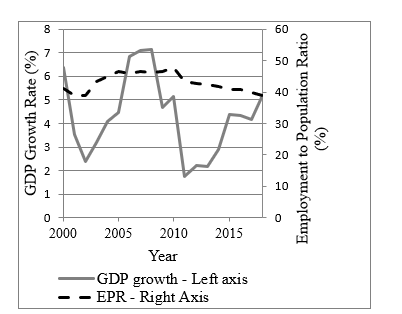

The Egyptian economy has experienced a substantial recovery in growth since the downturn that following the global financial crisis and the political instability that followed the January 2011 revolution. As Figure 1 shows, the rate of GDP growth increased from nearly 2% per year in 2012 and 2013 to more than 5% per year in 2018; and growth is projected to reach 5.5% in 2019 (IMF, 2019).

The recent release of the results of the 2018 wave of the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) allows us to assess the degree to which the recovery has resulted in improvements in employment conditions in Egypt.

The main conclusion we draw is that the quantity and quality of jobs in the Egyptian economy have not improved despite some improvement in job security among some of the most vulnerable workers, whose employment is particularly sensitive to the business cycle. Real wages have declined substantially as a result of the inflationary spike that followed the flotation and sharp devaluation of the Egyptian pound in late 2016.

Unlike previous recoveries, the quantity of employment – as measured by the employment-to-population ratio or, more simply, the employment rate – has not (yet) responded to the recovery in growth. The employment rate has, in fact, declined steadily since its last peak in 2010.

As Figure 1 shows, the employment rate in 2018, according to the official Labor Force Survey, was more than 8.5 percentage points lower than in 2010. The decline in employment rates is not translating into rising unemployment rates because of a slowdown in the growth of the labour force. This has been brought about in part by a temporary decline in the growth of the youth and young adult populations and in part by falling participation rates (Krafft et al, 2019).

Figure 1: Annual GDP growth rate and employment-to-population ratio, population aged 15+

Source: Assaad et al (2019) based on data from World Bank Development Indicators and CAPMAS Labor Force Survey.

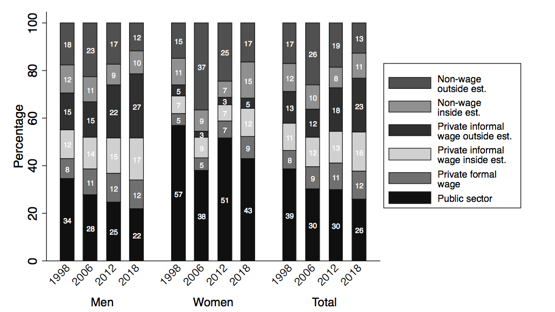

In terms of the composition of employment, the most notable trends have been the steady decline in the share of the public sector, a slow rise in formal private wage employment and a much more substantial rise in informal wage employment.

As Figure 2 shows, the share of informal wage employment outside fixed establishments has increased especially fast: from 12% of total employment in 2006 to 18% in 2012 to 23% in 2018. This form of employment is most vulnerable to job insecurity, as measured by irregularity of employment and involuntary part-time work. It also has some of the highest rates of exposure to occupational hazards and injuries.

The growth of these kinds of jobs is associated with the disproportionate growth of the construction and transport and storage industries in Egypt in recent years. The share of construction in total employment has increased from 8% in 2006 to 13% in 2018; and the share of transport and storage has increased from 6% in 2006 to 9% in 2018 (Assaad et al, 2019).

Figure 2: The structure of employment by type and sex, employed individuals aged 15-64, 1998, 2006, 2012, 2018.

Source: Assaad et al (2019) based on data from ELMPS.

The informalisation of employment has affected the Egyptian middle class particularly hard. While the bottom quintiles of the wealth distribution never had much access to formal jobs, the second to the fourth quintiles saw substantial declines in access to such employment, with much of the difference being taken up by informal employment outside fixed establishments.

The reduced access to formal employment is primarily the result of declining rates of public sector employment, with minimal growth in the share of formal private sector employment for the middle class.

A comparison of wages – whether monthly or hourly – between 2012 and 2018 shows that wages have not kept up with inflation over this period leading to an absolute decline in real wages. Median real monthly wages have declined by 9% over the period, after having risen by 6% from 2006 to 2012 (Said et al, 2019).

Similarly, median hourly wages declined by 11% from 2012 to 2018 compared with an increase of 12.5% in the previous six-year period. Declines in real wages were larger for women workers, for workers in urban areas, for medium and high skill workers compared with low-skill workers, and for private sector workers (both formal and informal) compared with public sector workers.

Wage inequality also increased substantially from 2012 to 2018 after being quite stable from 2006 to 2012 (Said et al, 2019).

Despite the generally negative trends of greater job informality and lower real wages, a few indicators of job quality showed improvement, namely those to do with the job security of informal workers.

The proportion of workers reporting irregular (that is, intermittent or seasonal) employment fell from 40% in 2012 to 30% in 2018 (Assaad et al, 2019). This kind of employment is particularly prevalent among wage workers working outside fixed establishments, who saw the extent of irregularity fall from 73% in 2012 to 53% in 2018. Irregularity also fell somewhat for wage workers in micro and small establishments, but from much lower levels.

Similarly, the extent of involuntary part-time work, a sign of job insecurity that is most prevalent among workers outside fixed establishments, also fell from 2012 to 2018, after having increased appreciably from 2006 to 2012.

Both these indicators are highly susceptible to the business cycle and have improved as a result of the overall improvement in the economy. Nevertheless, the rising proportion of workers working outside fixed establishments associated with the growth of the construction and transport industries increases the degree of worker vulnerability to the next economic downturn.

Further reading

Assaad, Ragui, Abdelaziz AlSharawy and Colette Salemi (2019) ‘Is the Egyptian Economy Creating Good Jobs? Job Creation and Economic Vulnerability from 1998 to 2018’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Caitlyn Keo (2019) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt from 1988-2018: A Gendered Analysis’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

IMF (2019) ‘Arab Republic of Egypt’, Retrieved October 9, 2019, from https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/EGY

Said, Mona, Rami Galal and Mina Sami (2019) ‘Inequality and Income Mobility in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).