In a nutshell

Production and exports in the MENA region remain concentrated in low value-added and capital-intensive sectors.

This problem is accompanied by the lack of skilled labour needed to move up the international value chain; at the same time, unemployment, especially among young people, is high.

For firms to find skilled labour, trade and investment measures are not enough; they must be coupled with enhancements in education and vocational training, encouraging creation of the skills that firms need to innovate and expand their activity into international markets.

Exporting firms are typically larger, more productive and more skill-intensive than their non-exporting peers. This suggests that there is an important link between international trade and the skills of the labour force. In general, the tougher the competition in international markets, the more likely a firm will be to improve its production processes, to innovate and to hire more skilled labour in order to export.

The intersection of trade and demand for skilled labour remains largely understudied in the MENA region, which is traditionally known for exporting fuel and low value-added manufactured products. But recent regional developments show that a large part of the old structures need to be revisited.

When it comes to industry and trade, the conclusion is the same: MENA economies are the most open group in the world, with a ratio of 44.7% of exports of goods and services to GDP. Most of them are also engaged in regional or multilateral trade agreements, such as the Greater Arab Free Trade Area, the EU-Association Agreements, and the World Trade Organization.

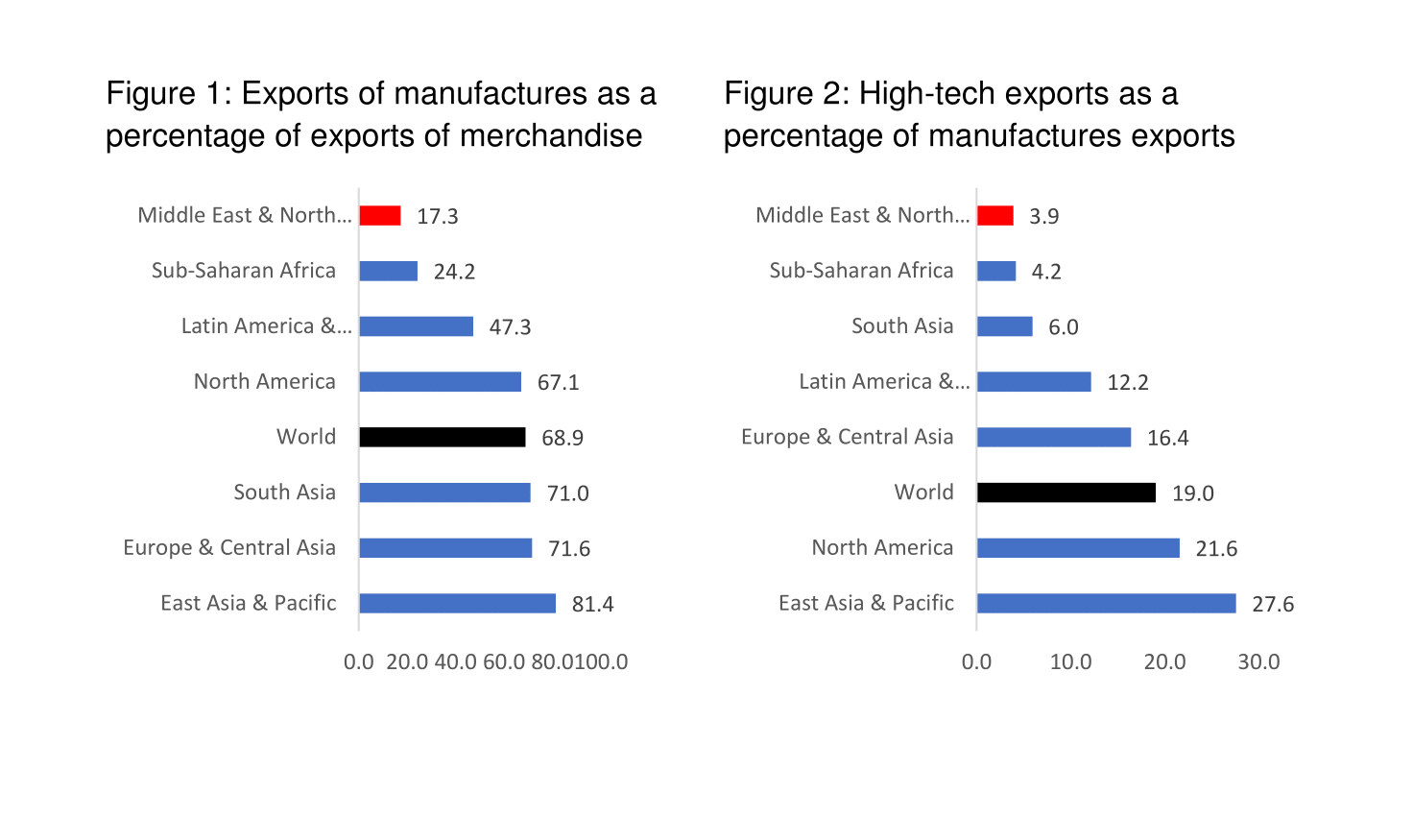

But a closer look at the composition of exports shows that 72.5% of these are mainly fuel, while only 17.3% are manufactured products. This latter ratio is not only extremely modest: it is also the lowest in the world compared with Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and the Pacific, and even sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 1).

An even closer look at the composition of exported manufactured products shows a minimal share of 3.9% of high-tech products within this segment of exports (see Figure 2).

The failure of MENA economies to upgrade their production and trade structures and to create for themselves new higher value-added niches within world trade is a complex and multifaceted problem.

On the one hand, the region suffers from the highest unemployment rates in the world, as much as 26% for young people. Women are also disadvantaged and many have precarious jobs. On the other hand, the region is known for its lack of employability (OECD, 2016): there is often mismatch between the needed skills to be hired and the existing qualifications.

In our research, we analyse data from the World Bank’s 2013 Enterprise Survey to examine the nexus between exports, innovation and the demand for skilled blue- and white-collar labour in eight MENA countries: Djibouti, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen.

In a first step, we examine the link between the exporting status of the firm and its innovative behaviour. In a second step, we examine the impact of innovation and use of technology on the demand for skilled blue- and white-collar labour.

Our findings suggest a positive and significant impact of exports on innovation and use of technology. Furthermore, demand for skilled production workers by firms in the MENA region is likely to be higher than that for non-production workers, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Formally registered firms are also more likely to demand skilled labour, and large firms are likely to have a higher demand for both blue- and white-collar skills.

These results allow us to draw a number of conclusions with high policy relevance. First of all, encouraging formality in the MENA region should be a priority: formality is the only way to benefit from credit from formal channels and outside informal circles.

Designing adequate incentive programmes for informal firms to join the formal sector (such as through enhanced access to finance and preliminary tax exemptions) can give a real push to the manufacturing sector, allowing firms to thrive, innovate and expand their activities into the exporting sector.

Furthermore, the main concern in the MENA’s manufacturing sector remains the lack of skilled workers to allow firms to upgrade, innovate, use sophisticated technology and enter new segments with high value-added in the international market.

In this context, the OECD (2016) argues that the two key constraints on employment in Arab countries are a lack of job creation and employability.

While the lack of job creation could by explained by the concentration of MENA manufacturing in low value-added products and capital-intensive activities, employability and lack of skills is the other side of the coin. More open trade policies and investment incentives for large firms as well as SMEs in the MENA region may act as a driver of job creation in Arab countries.

But there will be increased need to hire skilled workers in order to face fierce competition in international markets. Considering that most products exported by the MENA region are intensive in skilled blue-collar workers, the lack of serious steps towards enhancing the quality of vocational training is likely to offset any trade and investment policy efforts and limit their outcome.

This is why strengthening partnerships between business, government and universities will improve the provision of skills, boosting on-the-job training and the provision of quality apprenticeship.

Moreover, vocational training with double degrees (such as the Donbosco, an Italian-Egyptian technical school) can be useful for two reasons. First, they can raise the prestige of vocational work, which is often not well thought of in Arab countries. Second, they will improve the quality of vocational education and training, leading to enhanced skills to match the needs of exporting sectors.

Further reading

Aboushady, Nora, and Chahir Zaki (2018) ‘Do Exports and Innovation Matter for the Demand of Skilled Labor? Evidence from MENA Countries’, EMNES Working Paper No. 9.

African Development Bank (2012) ‘African Economic Outlook 2012: Promoting Youth Employment’, African Development Bank, Tunis, Tunisia.

Brambilla, Irene, Daniel Lederman and Guido Porto (2012). ‘Exports, Export Destinations and Skills’, American Economic Review 102(7): 3406-38.

OECD (2016) ‘Youth in the MENA Region: How to Bring Them In’, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Source: constructed by the authors using the World Development Indicators