In a nutshell

Easy access to data on business cycles is vital for the economy as well as for policy-makers and researchers.

The Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research has developed a chronology of Kuwait’s various spells of growth cycles of recession and expansions, together with the paths of the output gap and annual growth rates.

Business cycle dating is conducive to better planning by the private sector and better policy design by economic and financial gatekeepers of the economy.

Nearly all countries undergo good economic times followed by more difficult times. During periods of prosperity, incomes typically rise; people find abundant and attractive employment opportunities; and businesses enjoy growth in their sales and profits, which encourages them to invest more and build more enterprises and start-ups.

In contrast, during periods of hardship, incomes recede; jobs become scarcer as many people chase a limited number of job openings; while businesses contract and shops dismiss workers, causing rising unemployment and an increase in the number and proportion of the underprivileged, poor individuals and their families.

In ancient Egypt, for example, people experienced seven years of good weather and bountiful harvests followed by seven years of drought and famine. In modern times, countries that depend heavily on fishing and agricultural crops are often subject to periods of economic peaks and valleys that are dubbed ‘expansion’ and ‘recession’. These might be because of bad weather and poor crop harvest, or insufficient demand in local and/or export markets.

In economic jargon, these successive periods of good and bad times are called business cycles. The duration of business cycles depends on the underlying reasons that trigger them, such as drought conditions or the extent of a demand contraction in export markets, for example, markets for crude oil.

Analysis of business cycles is vital for the economy as well as for policy-makers and students and researchers. As Joseph Schumpeter (1939) remarked, ‘Cycles are not like tonsils, separate things that might be treated by themselves, but are, like the beat of the heart, of the essence of the organism that displays them.’

Kuwait, which depends heavily on oil revenues from export markets, does not have an official chronology of business cycles – one that determines the dates of the onset of recession (trough) and expansion (peak).

Such a chronology, which tracks and projects dates of expansions and contractions of overall economic activity, might be produced by one or more of the key economic institutions – the Central Statistical Bureau, the Central Bank of Kuwait or the Capital Market Authority – or by any of the country’s research institutions.

Absent too is any formal apparatus that monitors and anticipates the performance of the economy over the near-term horizon – the next six to nine months – in a systematic manner with periodicity and frequency that are announced and known to policy-makers and business leaders in advance.

In many countries, policy-makers, business leaders and forecasters can easily access data on historical economic and financial cycles as well as the current state of the economy in real-time. Such access helps agencies and authorities alike to devise appropriate policy responses and reorient action plans.

It is conducive to better business planning strategies by private sector leaders and for designing shock mitigation policy mixes by economic and financial gatekeepers of the economy, including central banks and the banking sector – and in the case of Kuwait, the Capital Market Authority, the Kuwait Chamber of Commerce, the Ministry of Finance and the Supreme Development and Planning Council.

The Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR) has initiated the process of bridging this gap by amassing and examining the properties of a large compendium of officially published data that vary in length and frequency. KISR then subjected the alternative data series to a suite of academic and business approaches, and analytically blended them to construct a provisional benchmark chronology of business cycles in Kuwait.

KISR then applied statistical analysis to the set monthly and quarterly data to gauge tentative business cycle dates that could be developed and validated further for application as signals of the future state of the Kuwaiti economy.

KISR is deploying data on a large number of series, including real estate prices and traded property size according to location, as well as data on various gauges of interest rates according to terms that cover the period from the start of 2000 to the end of 2016. Other monthly data series date back to the mid-1960s and early 1970s.

The analysed datasets also cover Kuwait’s exports and imports, government revenues and expenditures, the industrial production index (and similar indices for Kuwait’s major trade partners), the number and trade volume of stock market transactions, and banking credit loans to key sectors including the trade sector, the construction sector and the manufacturing sector, as well as personal and total banking loans.

In terms of methodology, KISR followed standard techniques (Hamilton, 1989) to arrive at business cycle recession probabilities and recession and expansion duration. In addition to annual and quarterly growth cycles, the analysis covers other time series data, such as oil exports, foreign exchange and the real effective exchange rate dating back to the start of 1965. KISR also used a model to generate a composite coincidental economic indicator for Kuwait.

In parallel, KISR research pursued the Conference Board’s (2013, 2015) approach to establishing and validating composite leading and coincidental economic indicators for Kuwait. A standard dating of turning points was also applied along with the growth cycle approach to generate tentative chronological order of cyclical patterns in Kuwait (KISR, 2018).

We followed standard approaches by considering the industrial production index as a proxy gauge of coincidental activity in the Kuwaiti economy. KISR validated this approach by growth cycles derived from annual GDP series covering about 67 years, from 1950 to 2016, to detect provisional economic downturns using a combination of growth cycles and output gap.

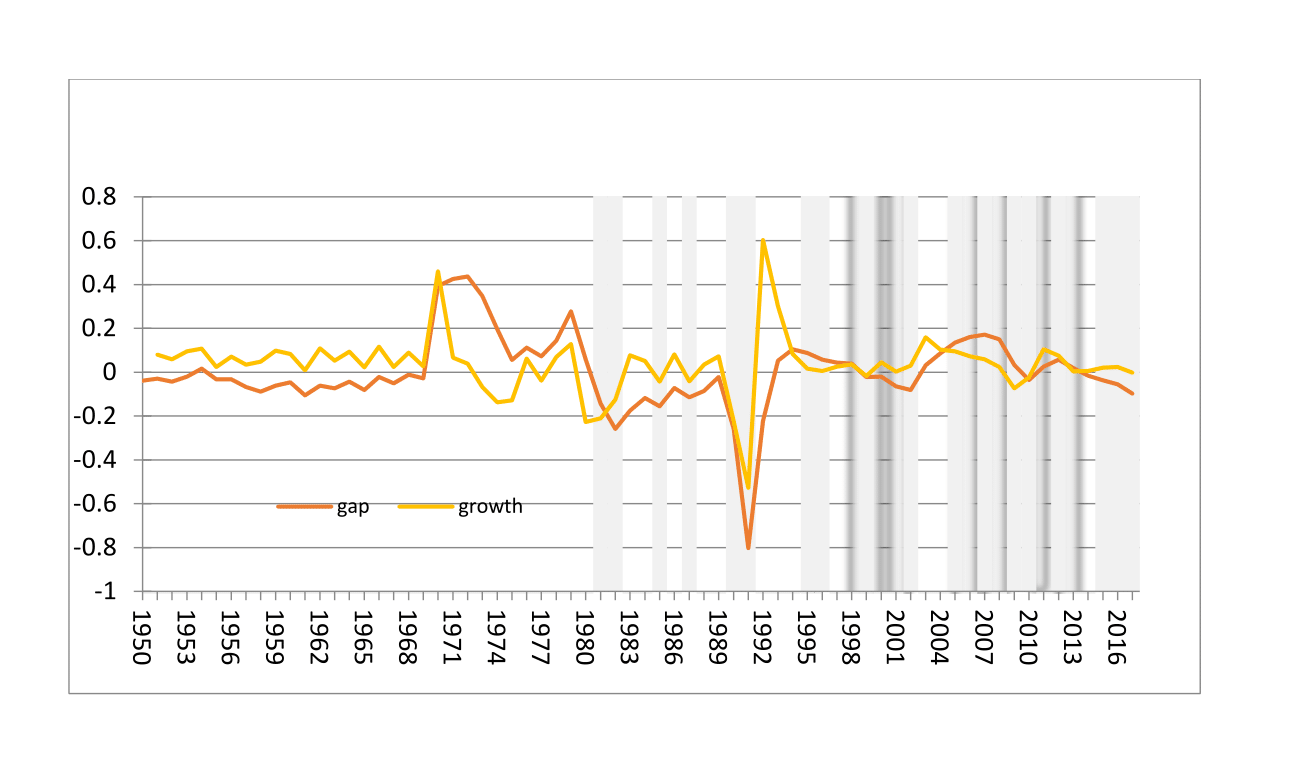

The timing of the various spells of growth cycles of recession and expansions, together with the paths of the output gap and annual growth rates, are portrayed in Figure 1. The grey areas indicate the timing of economic downturns or recession as derived from the growth cycles analysis.

Being somewhat novel and differentiated, the current research attempt should be construed as only the beginning of what we hope to be a successful effort to fine tune its amassed data, along with the blend of analytical infrastructures, in a way that serves future research and business needs in Kuwait.

Further reading

Conference Board and Gulf Investment Corporation (2013, 2015) ‘Measuring and Monitoring the Business Performance of the Gulf Cooperation Council’.

Hamilton, James (1989) ‘A New Approach to the Economic Analysis of Nonstationary Time Series and the Business Cycle’, Econometrica 57(2): 357-84.

KISR (2018) ‘Kuwait Economic Bulletin: Composite Headlines for Business Cycle Movements in Kuwait’.

Schumpeter, Joseph (1939) Business Cycles, McGraw-Hill

Figure 1:

Chronology of growth cycles in Kuwait, 1950-2016