In a nutshell

Global interlinkages foster labour market outcomes in MENA countries: through participation in GVCs, both job quantity and job quality are enhanced.

Investment in human capital is necessary to strengthen the positive effect on real wages and move up to higher value-added activities and escape the trap of dependence on trade in commodities like oil and gas.

Coherent trade and fiscal policies are key to supporting small and medium-sized enterprises participating in global markets; this will encourage the economic diversification that is necessary for fostering higher skill levels across the workforce.

‘Decent work for all’, as reflected in higher job quantity and better job quality, is a key sustainable development goal to be achieved by 2030. This ambition is particularly important for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), where unemployment is high and the annual growth rate per capita is 2.6% compared with 6.8% in middle-income counterparts outside the region (Islam et al, 2022).

What’s more, the demand for skilled labour in the region is constrained by a low-skilled workforce and high concentration on low-value-added extractive activities. In parallel, although participation in global value chains (GVCs) contributes to better labour market outcomes through a variety of channels, only a small fraction of MENA firms participate (Ayadi et al, 2024).

GVC participation contributes both directly and indirectly to increased returns and higher skills. First, the direct mechanism includes the production scale accompanying specialization, leading to higher real returns. In addition, because GVC is skill-biased, increased integration fosters demand for skilled employment, providing incentives for the acquisition of higher skill levels in the workforce. Second, due to the foreign learning effects of GVC participation, it indirectly fosters real wages through accompanying foreign knowledge, innovation, and skills.

In the MENA region, which is characterized by stagnant wages and low skills, facilitating firms’ participation in GVCs aspires to foster labour market outcomes. On the one hand, labour market conditions converge across participants in different regions. On the other hand, because of upgrading, demand for skilled labour increases, leading to more employment in higher-quality jobs.

Research on global value chains and labour market outcomes

In recent research (Eissa, 2024), we show that in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia, individuals working in firms that participate in GVCs – that is, importing intermediate goods and exporting – earn higher real wages on average than individuals working in non-participating firms. This GVC-driven effect on real wages is strengthened with skill requirements. In particular, jobs requiring skills strengthen the positive effect of GVC participation on real wages.

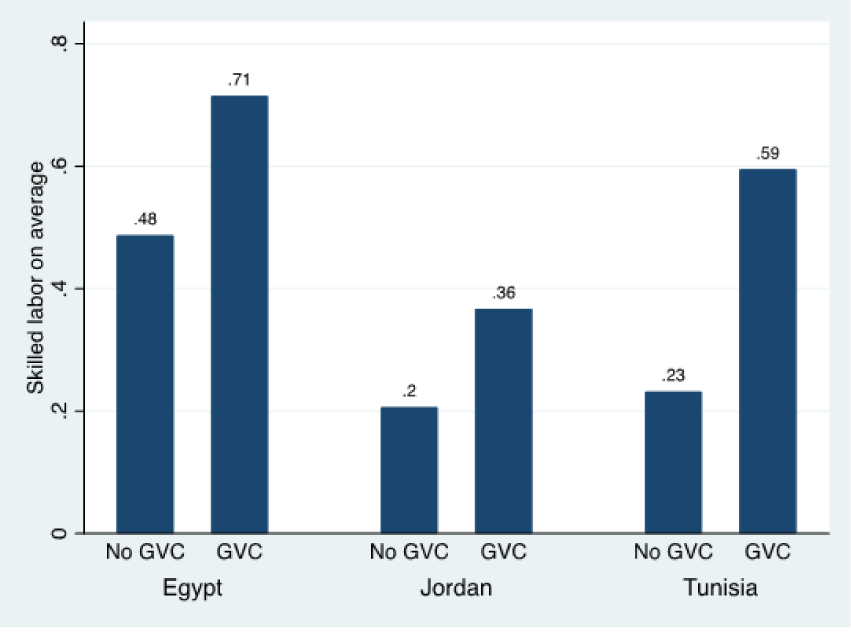

Furthermore, firms that participate in GVCs employ more skilled production workers than non-participating firms. As Figure 1 shows, firms participating in GVCs employ more skilled workers on average than non-participating counterparts.

Because of the transferability of skills and knowledge through GVCs, participating firms demand skilled workers with a higher ability to employ innovative inputs. On average, firms that participate in GVCs employ 30% more skilled production workers than their non-GVC counterparts.

Despite the foreseen opportunity to foster skill levels in the MENA workforce through GVC participation, the dynamics of this effect can be mitigated by commodity dependence. If GVC participation is limited and concentrated in low-value-added primary goods, realizing labour market prospects in terms of skills and job quality remains ambiguous.

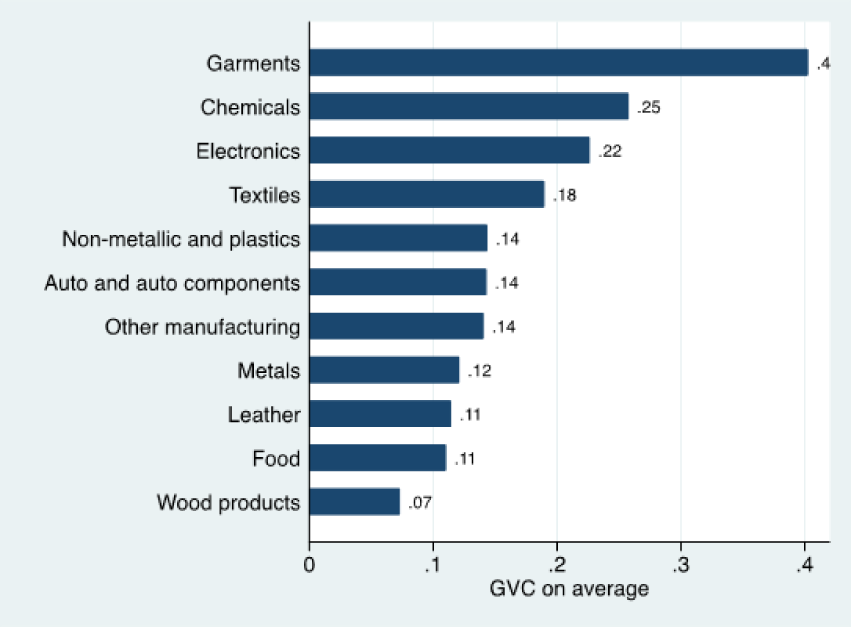

To escape the commodity trap, diversification of trade activities across industries is necessary. Figure 2 presents the shares of firms participating in simultaneous importing and exporting across manufacturing sectors. As presented, garments have the highest share in firms’ GVC participation on average in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia.

Notably, the apparel sector, characterized by its female-friendly nature, holds a relatively high share within GVCs. Promoting GVC participation in this sector can significantly enhance female employment opportunities and help bridge the substantial gender divide prevalent in the MENA region.

Figure 1: Skilled production workers across GVC, on average

Figure 2: GVC across sectors on average

Note: Figures averaging: Egypt years 2013, 2016, and 2020; Jordan years 2013 and 2019; and Tunisia years 2013 and 2020

Implications for policy

From a policy standpoint, recommendations to promote GVC participation to achieve ‘decent work for all’ in the MENA region are threefold.

First, at the trade policy level, reducing unnecessary trade costs facilitates the bottlenecked integration of GVCs in the MENA region with high non-tariff measures. Controlling trade costs and engaging in deep trade agreements particularly those with provisions for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will streamline the integration process and promote inclusive participation.

Second, facilitating GVC participation must be accompanied by coherent policies aimed at improving labour conditions. Investment in education, training, and entrepreneurship programs is essential for promoting skill levels. Skill upgrading is not only important for fostering higher wages, but it is also necessary for moving up to higher value-added activities across the chain and escaping the commodity dependence trap in MENA countries. In this respect, fiscal policy is key to allocating more spending on education and providing financial support to SMEs to provide training programmes for local employees.

Finally, strengthening labour laws to protect workers’ rights ensures decent working conditions, and fosters a productive ecosystem for attracting foreign labour and capital. Through GVC participation, foreign knowledge transfer incentivizes skills acquisition, boosts innovation, and enhances the global market competitiveness of MENA firms.

Further reading

Ayadi, R, G Giovannetti, E Marvasi and C Zaki (2024) ‘Trade networks and the productivity

of MENA firms in global value chains’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 69: 10-23.

Eissa, Y (2024) ‘GVCs and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from MENA’, ERF Working Paper No. 1730.

Islam, AM, D Moosa and F Saliola (2022) Jobs undone: Reshaping the role of governments

toward markets and workers in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Author’s note: This research has been supported by the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). It was funded by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Sector Project ‘Employment Promotion in Development Cooperation’, on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).